Man behind Cybertruck explosion broken by 2019 deployment, ex-girlfriend says

A former girlfriend of Matthew Livelsberger, the man authorities have blamed for a Tesla Cybertruck explosion at the Trump International on New Year’s Day, said his 2019 deployment to Afghanistan “absolutely broke him.”

Livelsberger, 37, a decorated military operations sergeant who served in the U.S. Army as a Green Beret, shot himself in the head, an act that Sheriff Kevin McMahill said was likely simultaneous with an explosion of fuel and fireworks in the Cybertruck. Seven people suffered minor injuries in the explosion.

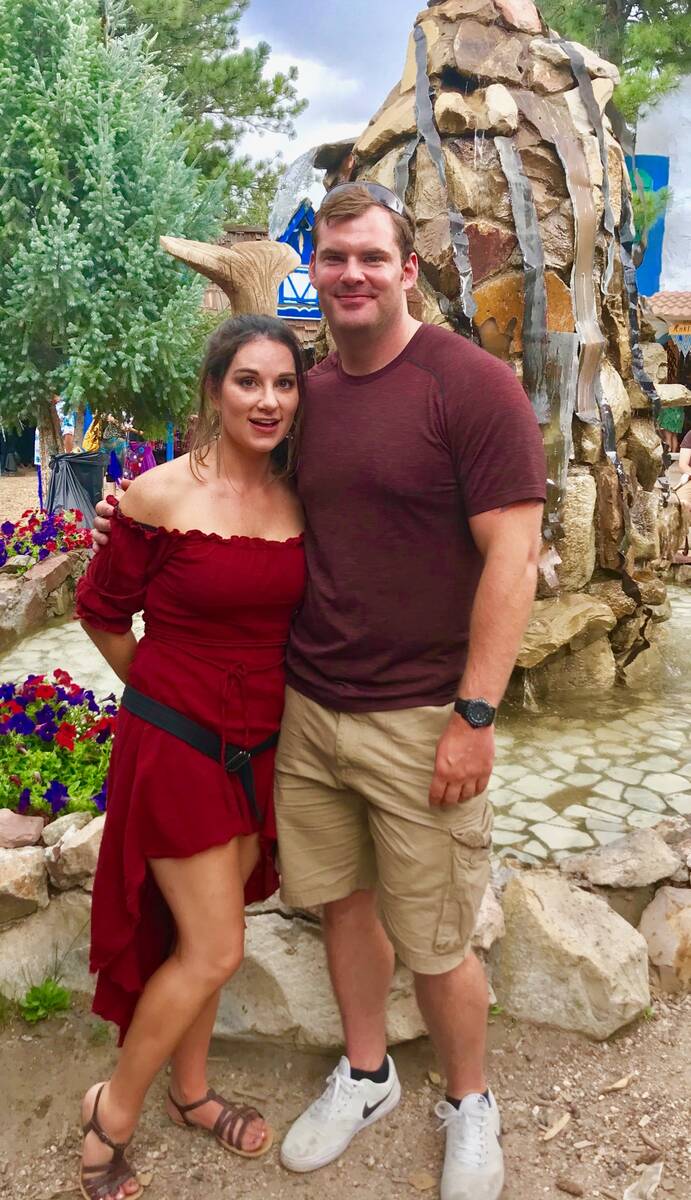

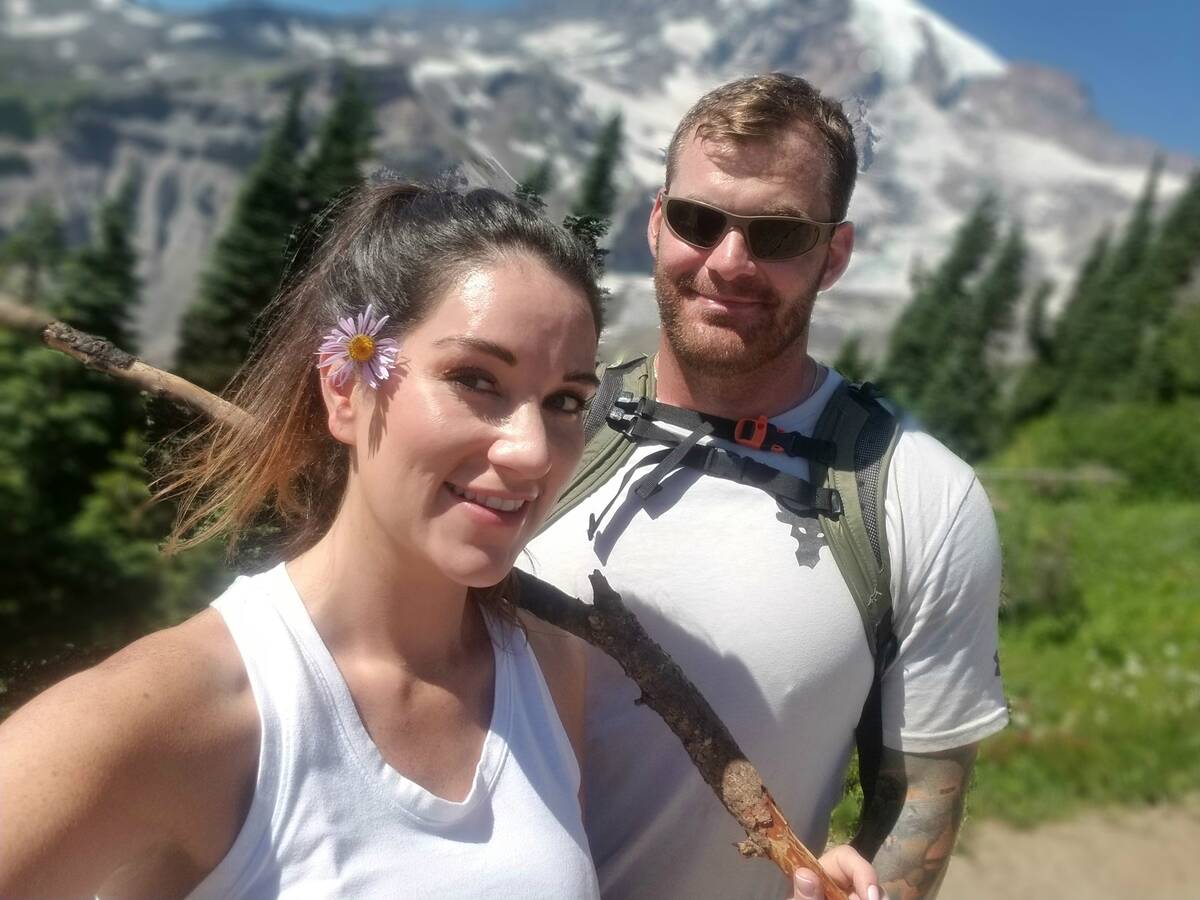

Alicia Arritt, a 39-year-old former Army nurse who met Livelsberger in 2018, said he had suffered brain injuries before his 2019 experience in Afghanistan but was able to cope with them.

After the 2019 deployment, he wouldn’t talk about what he went through, she said, and seemed ashamed.

“The weight of his conscience, he just couldn’t cope with it,” she said. “He just kept sending me messages about his depression.”

A note released by police indicates Livelsberger felt guilt about the people he killed.

“This was not a terrorist attack, it was a wake up call,” he wrote. “Americans only pay attention to spectacles and violence. What better way to get my point across than a stunt with fireworks and explosives? Why did I personally do it now? I needed to cleanse my mind of the brothers I’ve lost and relieve myself of the burden of the lives I took.”

Authorities have said Livelsberger likely suffered from PTSD and had other “personal grievances.” Spencer Evans, special agent in charge of the FBI’s Las Vegas division, said the incident appeared to be “a tragic case of suicide involving a heavily decorated combat veteran.”

‘Depth of character’

Arritt said she and Livelsberger met in Colorado Springs through Tinder.

On their first date, they talked for three hours.

“He just had a lot of depth of character,” she said. “He was strong. He was brave, but he was so humble about everything.”

Arritt said he was kind to her son. When her son started to become interested in sports in 2020, Livelsberger, who loved sports, bought him high quality baseball gloves and bats and taught him to play.

Livelsberger also liked woodworking and art projects. He visited her for Christmas in 2019, but he didn’t want to talk about what he’d gone through, she said. Instead, he and Arritt decorated wooden boxes together.

‘I get so hopeless’

During their relationship, Livelsberger was struggling with medical and mental problems, she said.

Arritt said he suffered blast and head injuries as well as severe headaches and underwent two back surgeries in the time she knew him.

“He said he just had some really hard landings in the dark a couple of times,” she said.

Livelsberger also dealt with weight gain and worsening flashbacks, Arritt said, and she believed he had suffered traumatic brain injuries. She said he had memory problems and trouble finding words.

At one point, she said, he failed out of a “spy school” course, which was unusual for him.

“He couldn’t cope with the stress,” she said. “He was having nightmares. He was having paranoia.”

According to messages provided by Arritt, Livelsberger spoke about undergoing mental health treatment.

He said in a 2018 message he was “going to do behavioral health” and in another message that he intended to start counseling but had been putting it off.

In a December 2019 message, he wrote, “Sometimes I get so hopeless and depressed.”

Arritt encouraged him to seek mental health treatment, but she said he didn’t want to do it.

“He was worried about the shame and stigma in his unit,” she said. “If you got mental health help, you were seen as weak and they didn’t allow any weakness in the unit. The Army celebrated his strength and ignored all of his pain inside. They give you medals. They gave him medals of valor for his bravery and they wanted all the pain of war to go away, and that doesn’t take away the pain.”

Livelsberger received numerous awards, including Bronze Stars and Army Commendation Medals, according to the Army.

Army spokesperson Bryce Dubee said the Army encourages soldiers to seek behavioral health treatment if they need it. The Preservation of the Force and Family program provides cognitive and medical support, plus other resources, he said.

Livelsberger used that program, according to Dubee. “(H)e did not display any concerning behaviors at the time, and was granted personal leave,” Dubee said.

Recent texts

Arritt’s relationship with Livelsberger ended around early 2021, but they remained friends until he married someone else and she kept her distance, she said.

Days before the explosion, Livelsberger texted Arritt, asking if she was single, according to text messages she provided. She thought he was looking for a hookup and said she shut him down.

They kept texting back and forth and he told her about the Cybertruck.

“I feel like Batman or halo, ” he wrote.

Arritt said he didn’t explain why he’d rented a Tesla, but they had connected in the past when they worked on a wrecked Tesla she found at an auction.

Nothing in the recent texts raised alarm bells, she said. She said she never talked with him about Las Vegas, and he didn’t tell her he was going to the city.

When she learned about his death from the FBI, she was shocked, she said, because he had just been messaging her, telling her she was a strong woman and a good mother.

“I had no idea how much he was suffering,” she said.

If you’re thinking about suicide, or are worried about a friend or loved one, help is available 24/7 by calling or texting the Lifeline network at 988. Live chat is available at 988lifeline.org. Additionally, the Crisis Text Line is a free, national service available 24/7. Text HOME to 741741.

Contact Noble Brigham at nbrigham@reviewjournal.com. Follow @BrighamNoble on X.