Meet Nevadadromeus, the first dinosaur unique to the Silver State

Joshua Bonde was hunting for fossils with students from Montana State University, in the backcountry of Valley of Fire State Park, when a hailstorm stopped the group in its tracks.

With eyes on the ground, and with the moisture from the storm creating enough contrast on the ground, the group began to see bones materializing in the buff, tan sediment.

“We were hunkered down right on the spot on the edge of this hill, just looking down at the right spot, at the right time, with the right set of eyes,” Bonde said.

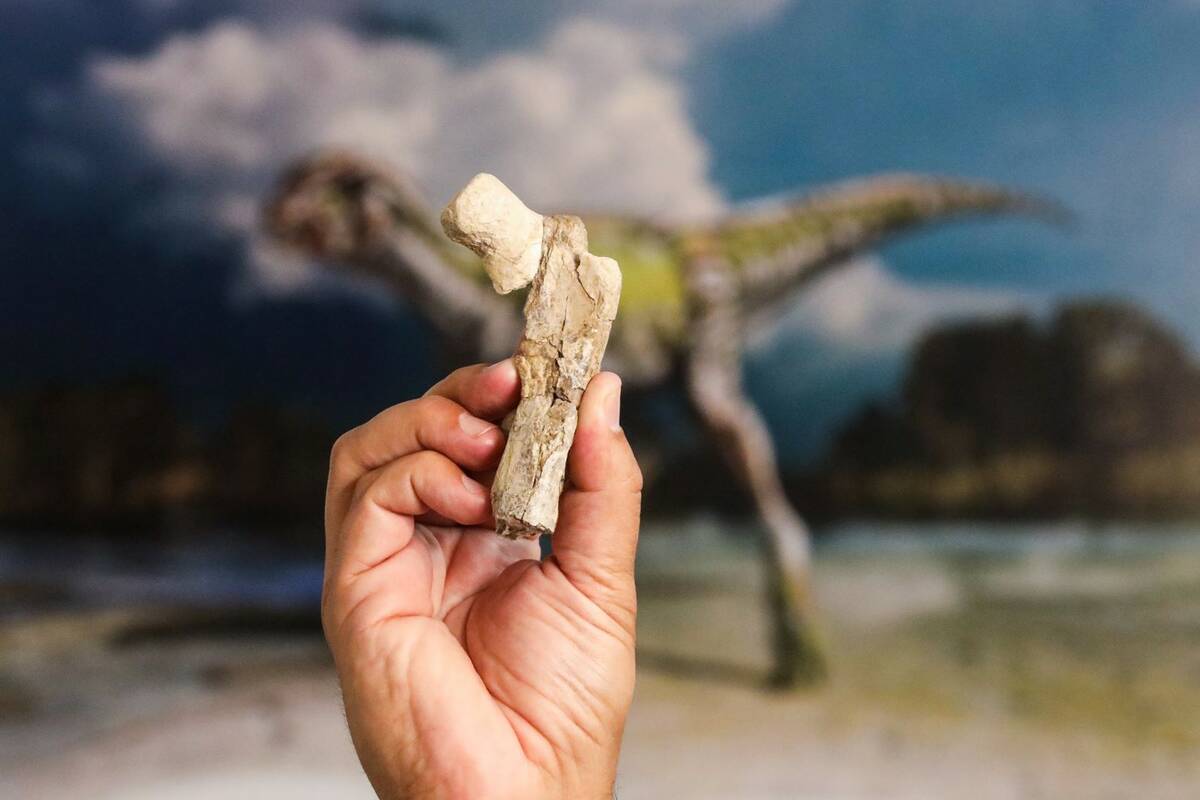

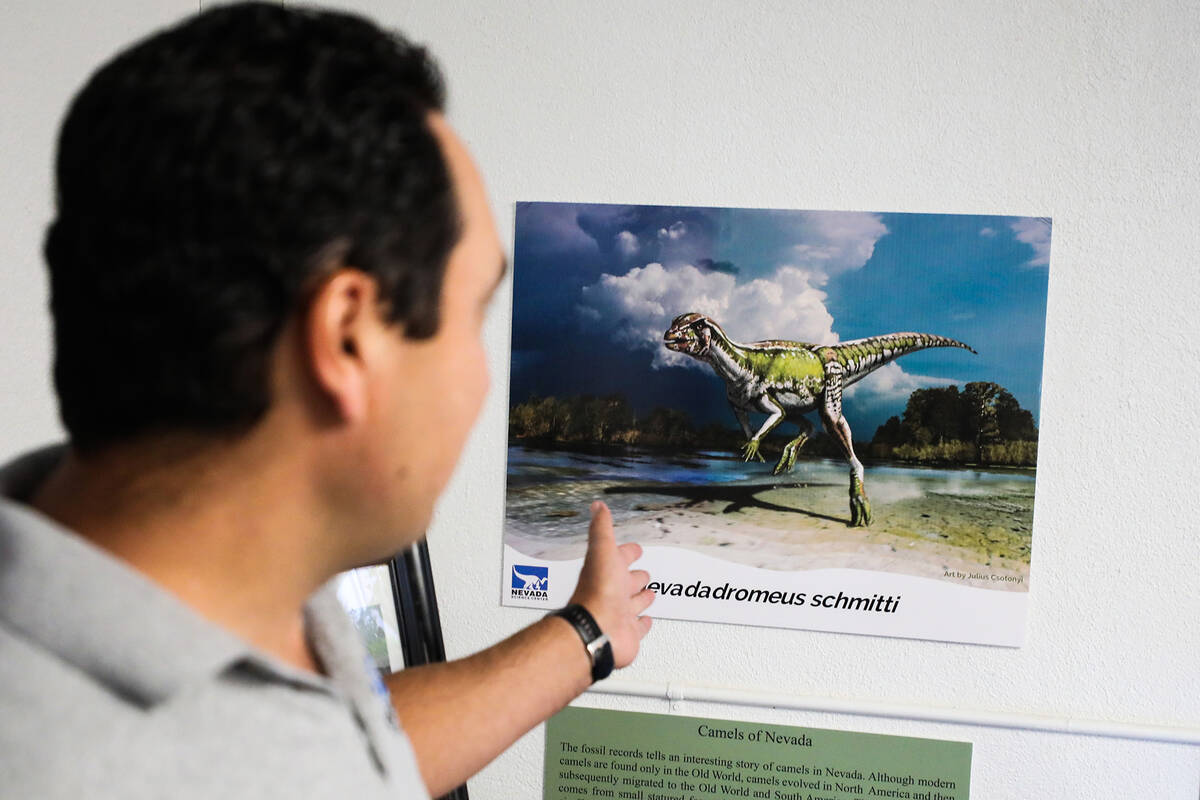

The fossil, which they discovered in 2008, would slowly be unearthed over the course of a decade and would eventually come to be known as Nevadadromeus schmitti, the first dinosaur unique to Nevada.

Bonde said the significance of the discovery was lost on him and his team at the time.

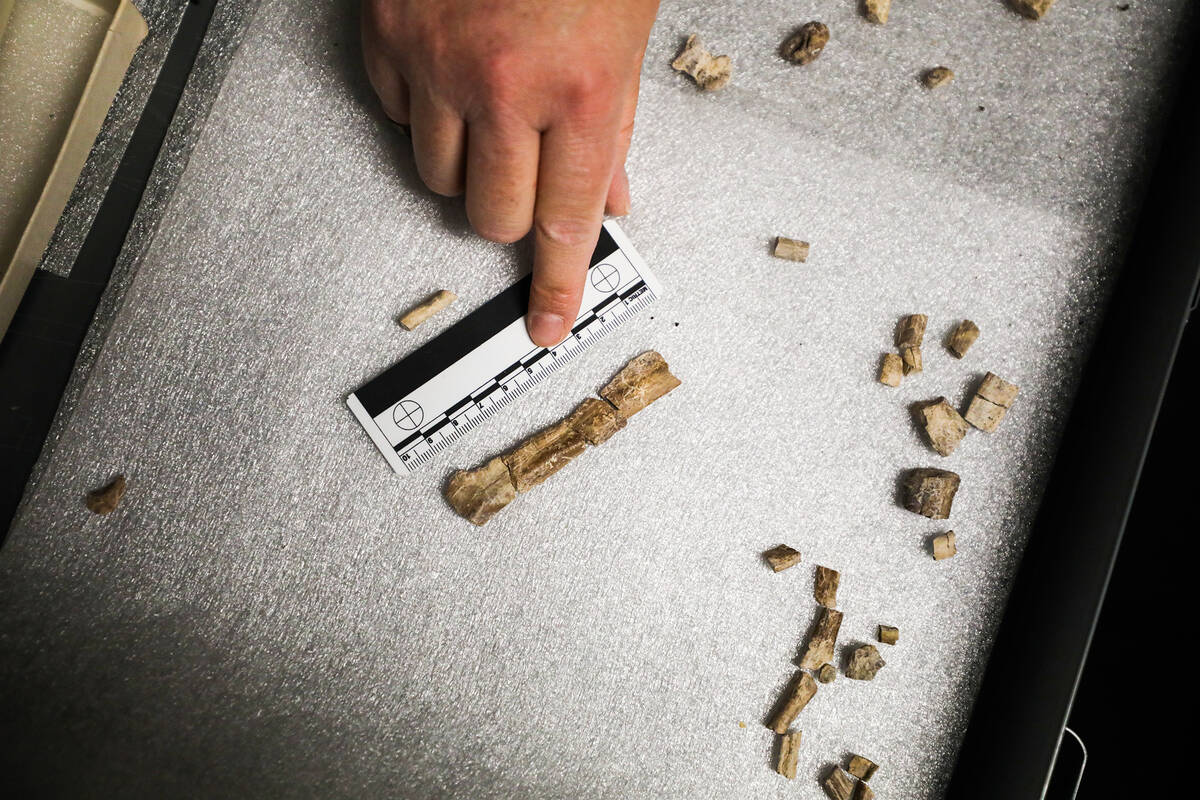

It wasn’t until they got back to the lab and started piecing the fossil together, “like a jigsaw puzzle,” over several years that they discovered the fossil carried traits of dinosaurs that lived in North America 20 million years after sediments that were deposited in Valley of Fire.

“It took us a long time to figure out it was really significant,” he said.

While Nevadadromeus was unveiled last fall, Bonde and his wife and fellow paleontologist Becky Hall announced last month that their paper describing the dinosaur had been accepted for publication in the Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science.

This latest development is important because a dinosaur isn’t official to the scientific community until its name, and the reason it’s being defined, have been vetted by other scientists in the process of peer review, Bonde said.

“(Nevadadromeus) will be its official name,” Hall said. “There’s not another species in Nevada like it right now.”

‘Sheep’ of Cretaceous period

The Nevada dinosaur is a thescelosaurus, what Bonde describes as “the sheep” of the Cretaceous period: a small-statured, plant-eating dinosaur that ran on its back legs and had a beak at the front of its mouth and teeth on its cheeks.

“The surname ‘dromeus’ means ‘runner’ in Greek,” Bonde said. “That’s kind of the joke is that they were running away from everything else trying to eat them.”

Nevadadromeus schmitti is named in part for the Silver State, but also for Jim Schmitt, a professor of geology at Montana State University, where Bonde obtained his master’s degree in geological and earth sciences.

Schmitt, who studies the ancient environments and ecosystems that existed when rocks were deposited as sediment, was a geology professor at UNLV from 1982 to 1984. During that time he became interested in the rocks at Valley of Fire, which are the same age as dinosaurs that roamed the earth during the Cretaceous period.

During their overlapping time at Montana State, Bonde was studying a rock formation at Valley of Fire when Schmitt mentioned that he should keep an eye out for dinosaur fossils in the park.

“I sort of just said, ‘Well, I think there’s probably dinosaur fossils there because the rocks are kind of the right age,’” Schmitt recalled of the conversation. “Being an educator, I kind of say things like that to students a lot, just give them advice or suggest something to them, and then they go run with it on their own.”

When Schmitt heard last year that Nevadadromeus had been named after him, he called it a shock.

“It’s not something that happens every day,” he said with a laugh.

‘Geologic wonderland’

Schmitt called the landscape around Las Vegas a “geologic wonderland” for geologists to study, uncovered by forests and easy to see and explore.

“It’s a really, really interesting place with a fascinating geologic history,” he said.

It’s a history that Bonde and Hall are working to educate the community about. The couple co-founded the Nevada Science Center in Henderson, where they teach the community about paleontology and geology through hands-on programming.

They also have continued their work uncovering fossils around the state, including a 25-foot dinosaur in Valley of Fire that Hall is excavating, and whose femur was discovered after a member of her crew was sitting on it as a stool while eating lunch.

“We were done for the day and packing up and all of a sudden the rock that he was sitting on … that’s the femur to the dinosaur,” she said.

The experience demonstrates the inherently slow process of looking for and uncovering fossils. In some instances, Bonde said, Mother Nature will expose more and more pieces of a fossil as time goes on, like in the case of Nevadadromeus.

But other times, like with the fossil Hall is currently excavating, paleontologists must work against Mother Nature and various geological processes, slowly and methodically chiseling away at rock, to uncover a fossil.

“When we’re looking for fossils, it’s really slow. If someone’s walking at a normal clip, you’re going to walk right past it,” she said. “Even for us we feel a little bit lucky, too, that just slowing down, you can find them.”

Contact Lorraine Longhi at 480-243-4086 or llonghi@reviewjournal.com. Follow her @lolonghi on Twitter.