Storm Area 51 still affects tiny Nevada town a year later

It seems closer to a generation ago than 12 measly months.

Long before the 2020-ness of life began pulverizing us on a daily basis — back when the biggest thing many of us were concerned about was whether we’d ever get our hands on one of those Popeyes chicken sandwiches — the world was obsessed with how many people would descend on a tiny blip on the Nevada map, 50 miles from anywhere, called Rachel and what they might do when they got there.

Sunday marks the first anniversary of the day on which more than 2 million Facebook users, responding to a college student’s late-night goof, had pledged to storm Area 51 to “see them aliens.”

As a result of that random joke, Lincoln County is out $200,000, two small-business owners lost a combined $250,000, litigation is pending and Rachel has become divided, with many of its residents — all of whom could safely gather without violating the state’s 50-person coronavirus guidelines — no longer speaking to one another.

‘I’m still not unwound’

“In this last year, we’ve been hit so hard, we’re barely treading water,” Connie West says.

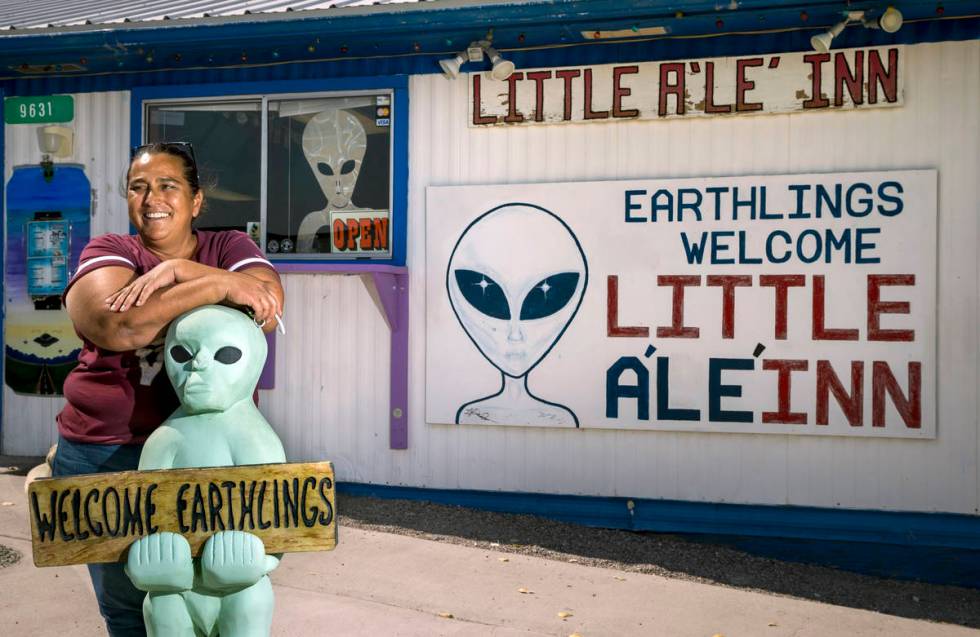

As the proprietor of the only business in Rachel, the nearest thing resembling a town to Area 51, she and her Little A’Le’Inn were thrust into the international spotlight in July 2019 as that Facebook prank went viral.

Plans to breach the nearby gate of the secretive military facility morphed into an ambitious music and arts festival dubbed Alienstock. The event was thrown into disarray days before, on Sept. 9, when the man who coined the phrase “Storm Area 51” severed ties with it. The resulting four-day festival, put together at the last minute, offered the couple of thousand people curious enough to attend more of a DIY vibe.

“I’m still not unwound from it,” West says of that wild summer that found media from around the world wandering into her small cafe, “because I have to deal with the aftermath of it every day.”

That aftermath includes a lawsuit and countersuit involving the meme’s creator and his team, as well as the wrath of some members of her once-close-knit group of neighbors who remain angry with the way things played out.

“I’ve known these people for a long, long time. … Alienstock made me see some ugly in people that I never thought were that deep and ugly, right here in my community.”

West estimates the event cost her $200,000, and that tab keeps climbing because of the legal bills. She’s due in court again in late February.

None of that, though, is deterring her from attempting to host another festival.

“I put a hell of a lot of work into it,” she says of the 2020 edition that was scuttled in May as a result of the pandemic. “I had some awesome sponsors. Due to COVID … I kind of pulled the plug on it, because I knew that my commissioners and everybody else in the county and the state had other things they needed to worry about.”

She says those sponsors are willing to work with her again, whenever it’s deemed safe to try, be it next year or 2022. A handful of enthusiasts camped out across the highway from her establishment last weekend, when this year’s festival would have taken place.

“All year, people have reached out to me,” West says. “They want this to happen again — however it happens and whenever it happens — and I’m grateful to try to do it again.”

‘A lot of animosity’

Joerg Arnu wishes with all his might that West would just throw in the towel.

“The event has deeply divided our town into two camps,” the Rachel resident says. One group backs West and her plans; Arnu leads the other. “There’s a lot of animosity all of a sudden. Rachel was a very friendly town, where everybody knew everybody, everybody greeted everybody, waved at everybody. Now it’s come down to the exact opposite. Nobody even wants to talk to anyone anymore. The two camps don’t talk.”

Last summer, Arnu used his position as the webmaster of Rachel’s official online platform to attempt to scare away visitors during that fateful weekend. A year later, the most prominent feature of the website is a link to his sister site reading “No Alienstock in Rachel.”

The retired software developer represents a group of eight families that he says own about 30 percent of the property in Rachel. Since the Alienstock festival, Arnu says he’s been harassed, had strangers trespass on his property and has been photographed inside his home via long lenses. He complains of tourists driving through the residential areas of Rachel, and he has reinstalled the security lighting he bought last summer after hearing cars near his property at night.

It may sound extreme, but you typically wouldn’t relocate to a spot so remote — it’s 45 miles from the nearest gas station and 80 from the closest emergency room — if you’re even somewhat tolerant of being bothered.

“Our town that was a very peaceful and quiet place, and friendly place, has changed,” Arnu says. “At this point, a year after the event, I don’t know if it will ever mend, if it will ever go back to how it was.”

One thing that won’t change, though, is his animosity toward similar large-scale festivals in Rachel.

“I will fight another Alienstock,” Arnu says, “with everything I have.”

‘All over the world’

With so much of the focus on Alienstock, you could be forgiven for not remembering that it wasn’t the only alien-themed festival that weekend.

Area 51 Basecamp at the Alien Research Center in Hiko also had grand ambitions. Pioneering British DJ Paul Oakenfold was so excited by its prospects, he flew from England on his private jet to perform — for free — on opening night, says George Harris, who owns the tourist attraction.

Still, so few gawkers showed up, plans for the rest of the festival were scrapped, and those tickets were refunded.

“I don’t think we have anything to be embarrassed about,” Harris says. “And, by the way, I lost a lot of money, because I really thought there was going to be about 25,000 or 30,000 people, so we prepared for a lot.”

Instead, 8,500 people stopped by over the course of a couple of days, he says. That discrepancy cost him $42,000, and Harris says it will take him four or five years to pay off the bank loan.

Still, he sees only the positives.

“I got at least $8 million in worldwide advertising,” Harris says. “We were literally all over the world for four days. … We were probably in the news cycle for a good, solid 30 days.”

The Alien Research Center was busier than normal for the next several weeks, and Harris says visitors still can’t get enough of his “I Stormed Area 51” merchandise.

Like West, he plans to do it all over again.

One iteration of the festival had been planned for Oct. 10-11, but COVID-19 took it off the schedule. He’s hoping to try again in the spring as a way to spread the word of extraterrestrial life, not to try to recoup his losses.

“Look, when you’re out in the middle of nowhere,” Harris says, “and you have a place because you’re a ufologist, and it’s your hobby and you love it, you’re not going to become rich.”

‘It was very stressful’

Storm Area 51 was Eric Holt’s first big test as Lincoln County’s emergency manager.

He’d been on the job for 18 months when calls started pouring in from around the world, accompanied by fears of more than 100,000 visitors. Even with smaller crowds, the events were a logistical nightmare, taking place in a rugged, punishing environment with almost no infrastructure.

“It was very stressful,” Holt recalls. “We spent a month and a half straight just dedicating all of our resources to planning efforts for this.”

At any given time, he says, there were around 3,000 people staying in Rachel, with what he estimates as 5,000 to 7,000 attendees for the weekend.

“That’s still kind of unheard of for up here,” Holt explains, “but it wasn’t anywhere near what we thought we’d see.”

To put those numbers in perspective, 3,000 people coming to a town that’s generously said to have 50 residents is roughly the equivalent of four years’ worth of pre-COVID-19 Las Vegas visitors descending on the city at once.

All that preparation doesn’t come cheap. Holt says the county’s final costs for that weekend topped $200,000, and that was only because several other agencies offered their services at no charge.

“If we would’ve had to pay for all the equipment and personnel and things that were there,” he says, “it would have been over $1 million easy.”

Lincoln County commissioners were able to pry the $200,000 from the general fund, Holt says. Then COVID-19 hit and squeezed the limited resources even further. It could take years, he says, for the full economic impact to be felt.

Initially, there were hopes that money would be reimbursed by the state. The process is ongoing, but Holt says Gov. Steve Sisolak has indicated that help from Carson City isn’t likely.

“We’re a little disheartened by that,” he says, “but we’ll survive. That’s what we do out here.”

‘Wow, that really happened’

Matty Roberts doesn’t seem like the sort of person who could leave a trail of devastation in his wake.

A year after his silly idea became a global sensation, the Bakersfield, California, resident is just an affable 21-year-old, working in a vape shop, waiting for his college classes to resume in person and hoping one day to become an electrician.

“I sit here, and I just kind of think about it like, ‘Wow, that really happened,’” Roberts says. “And it’s kind of wild to me. It almost feels kind of like a wild fever dream in a way, but I lived that. And that’s kind of bonkers to me. That’s a story not a whole lot of people can tell. I kind of wanna write a book.”

Does he think he ever will?

“Not really,” Roberts admits. “It’s a cool idea to play with, but I haven’t taken an English class since probably 2015, so I don’t think it would be a very good book.”

That initial post — encouraging people to meet up, originally in Amargosa Valley, and storm the facility at 3 a.m. Sept. 20 — was born out of late-night boredom as Roberts played World of Warcraft while scrolling through Facebook and watching self-proclaimed Area 51 whistleblower Bob Lazar on Joe Rogan’s podcast.

“I got real excited when I started to see, like, 400 people had RSVP’d to it,” he recalls, “and then, before I knew it, it was this international phenomenon. I’ve got people from, like, Czechoslovakia messaging me.”

Once it sparked, the attention wouldn’t stop for months.

“It just took off like wildfire,” Roberts says. “From that point on, I was just like, ‘Oh man, the FBI’s going to show up.’ And they did. And I’m pretty sure I’m still on a watchlist.”

After he pulled out of the Rachel event, Roberts ended up hosting a party Sept. 19 at the Downtown Las Vegas Events Center, which served as a launch for Bud Light’s limited-edition Area 51-themed beer.

Similar parties were planned there for June and this weekend — a tour of the East Coast with escape rooms and obstacle courses was in the works — but COVID-19 stopped all of it in its tracks.

Roberts says he made some money selling T-shirts online early last summer. Asked if he has any regrets, though, he can come up with only one: Rather than building his own website, he wishes he’d just sold those shirts through Amazon.

“I’ve had quite a few people that kind of mentioned that they thought I made millions from this thing,” Roberts says. “But I never really wanted to market it too much. I’m still just kind of like the college kid that works at the vape shop.”

Still, though, he has trouble letting go of Alienstock — the rights to which are part of the legal dispute with West. Regardless, he plans to ramp the whole thing up again some day.

“Absolutely. I mean, if we can, I would love to,” Roberts says. “I think whenever it is, and if it is safe to gather again, I’d really like to kind of just keep pursuing the dream.”

Contact Christopher Lawrence at clawrence@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4567. Follow @life_onthecouch on Twitter.