The little-known history of Goldfield’s paste-eater grave

GOLDFIELD — Inside the Goldfield Cemetery, past the Protestant, Catholic and Masonic plots lie the bodies of the mining town’s unknown, unclaimed and impoverished dead.

But one plot in this Potter’s Field in particular has become something of a rural Nevada roadside attraction in recent years: a headstone marked “UKNOWN MAN DIED EATING LIBRARY PASTE,” with the death date July 14, 1908.

An article published in the Carson City Daily Appeal on July 21, 1908, gives some insight into the unknown man’s final moments, stating that a local doctor during a post-mortem examination determined that the man “must have been nearly dead for something to eat, and had devoured the paste, which killed him within a few hours.”

The only thing on his person, the article states, is a “letter in his pocket addressed to ‘Mr. Ross, Goldfield, Nev.’”

But there’s one man in Goldfield who is working to make the stories of its long-dead known.

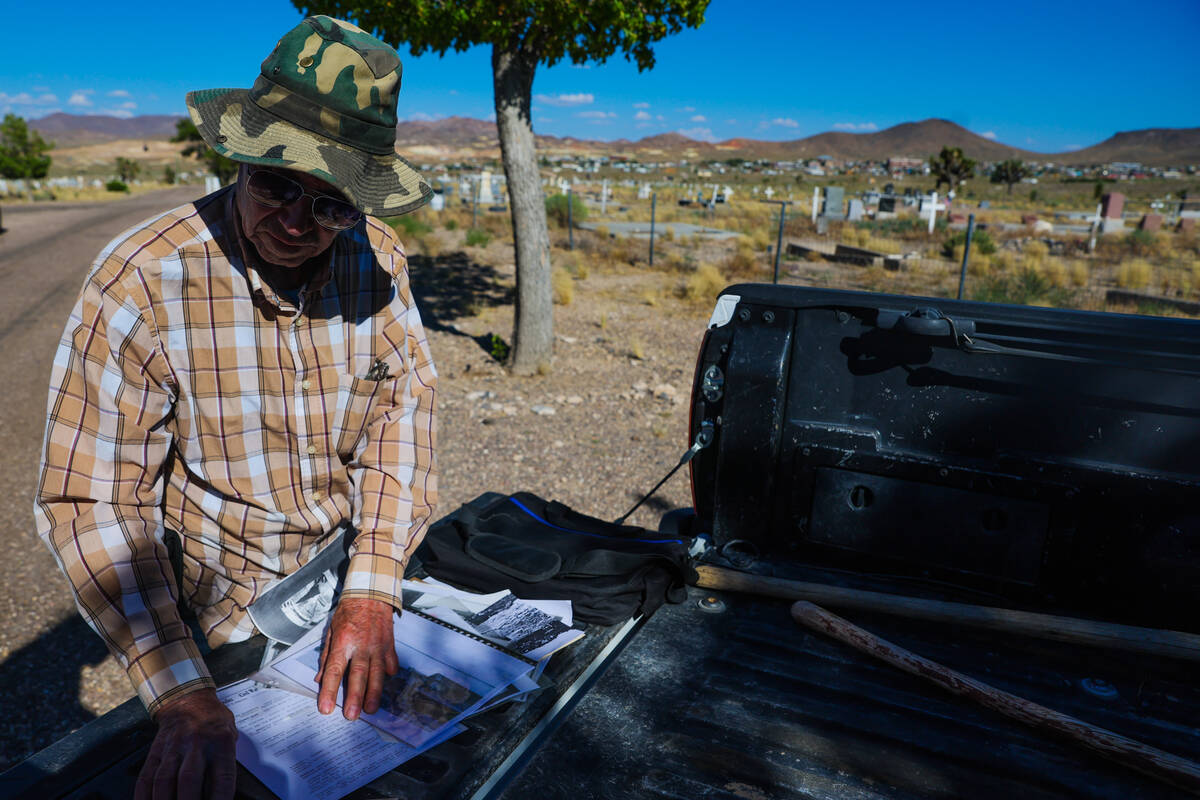

Allen Metscher has spent the last 45 years researching and marking the graves of pioneers buried both in Goldfield and in the Tonopah Cemetery, located next to town’s world-famous (and, to some, unsettling) Clown Motel.

While giving credit to his genealogist wife and newspaper archives for helping him find forgotten Goldfield history, he says the tool that has been his greatest help in finding unmarked graves are his dousing rods — metal wires he holds in each hand that cross each other over graves, and uncross when over plain dirt.

“You don’t put any pressure on them,” Metcher says as he walked past plots in Goldfield Cemetery’s Catholic section. “You walk over a grave, they’ll cross, you walk between graves, straighten out.”

And, by seemingly supernatural forces, they do, although forensic scientists say the practice is mere pseudoscience.

Metscher says he used the technique to mark then-unknown graves in Tonopah in the 1970s. When he came across a plot map for the cemetery in an attic in Round Mountain years later, he found that his dousing rod markings matched up almost exactly with the map.

He’s still trying to figure out several unmarked graves in the Potter’s Field, but he said he knows there are graves there — thanks to the rods.

Metscher has marked dozens of graves across the cemetery with small metal signs stamped by hand that add details about the deceased’s lives: Their military service, their cause of death and other genealogical information that give insight into what life was like over a century ago.

“Each one of those grave sites that I do research on — boy, it really tells you how rough it was in the old mining camps way back at the turn of the century,” he said.

Metscher even includes personal characteristics and other information directly from funeral records and obituaries, he said.

On the grave of a man known for being a piano player in Goldfield dance halls, Metscher writes that he “LIKED HIS DRINK.”

On an English immigrant’s grave, a metal marker states “LOST HIS WIFE & KIDS TO ANOTHER MAN.”

On another, from a sex worker, aged 21 and employed in Goldfield’s Red Light District, Metscher made a plaque that states her final words, written in a note she left before her death: “I WAS NEVER CUT OUT FOR THIS KIND OF WORK. I’M ONLY A KID.”

It takes him around 45 minutes to stamp the letters into each plaque — though, because he’s left-handed, he sometimes stamps his fingers instead of the metal, leaving his nails stained with a silver sheen.

Metscher said identifying graves became his hobby after working at a funeral home in Tonopah when he was fresh out of high school.

“Maybe you’d call it a morbid interest,” he joked.

But even before the funeral home, he and his brothers, Philip and Bill, who formed the Historical Society and Central Nevada Museum in Tonopah, had always been interested in history, he said — particularly because of their grandfather who moved across the world to Goldfield with “gold fever,” and later died from injuries in a mine cave in, leaving his grandmother, father and uncle destitute.

What has encouraged him to continue the work after four decades are the people who contact him looking for information about their buried relatives, he said.

His knack for navigating death records also led him to work with Nellis Air Force Base, where he wrote and researched the history of the Tonopah Army Air Field where 110 airmen lost their lives — the majority in plane crashes.

Over the years, he’s been interviewed by roughly 150 people looking for information about their family members, or has taken people on tours of the ancestor’s graves, he said.

“I was always interested in history, and every one of these people has got a little history.”

Contact Taylor Lane at tlane@reviewjournal.com.