Water rights: Feds could place burden on Las Vegas to protect California farms

The federal government laid out a pair of options Tuesday to drastically cut water use along the Colorado River and keep Lake Mead and Lake Powell from crashing any further in the coming years.

One of the proposals would impose hefty cuts following a strict priority system, which would protect the California agricultural sector’s water rights while placing the heaviest burden on cities like Las Vegas and Phoenix, while the other proposal would share those reductions more proportionally across Nevada, Arizona and California.

Both alternatives would impose cuts of nearly 2.1 million acre-feet in total at the most in 2024, with the steepest cuts triggered the lower Lake Mead falls. Larger cuts also would be imposed in 2025 and 2026 under both scenarios, totaling up to 4 million acre-feet in reductions if needed, or roughly 25 percent of the river’s annual allocation. The government also will consider a “no action alternative,” which looks at what would happen if no further cuts are made.

The plan will be open for public comment for 45 days, and a final proposal is slated to be adopted this summer.

Deputy Interior Secretary Tommy Beaudreau characterized the proposals not as a choice between one or the other, but rather two bookends of a spectrum of cuts that represent the next step in the process for the federal government in revising the current operating guidelines for how the basin states will deal with shortages through 2026 when those guidelines expire.

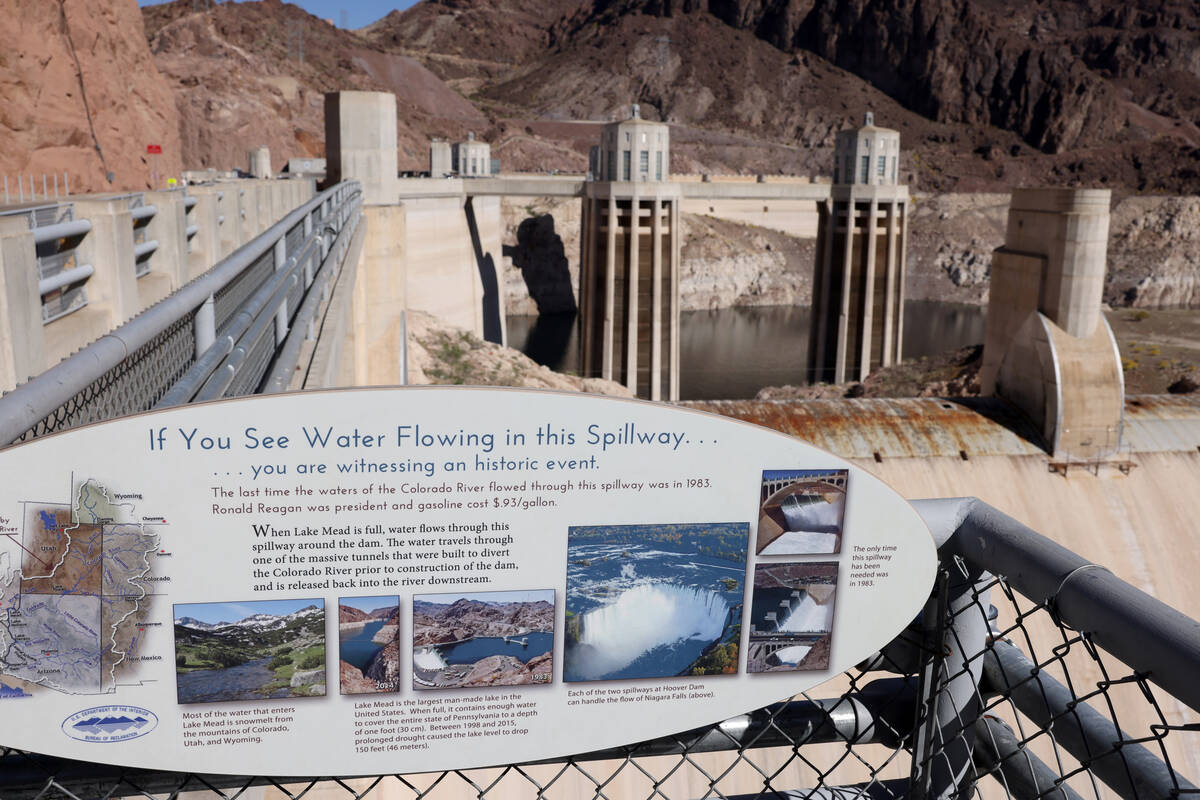

“We’ve defined a spectrum. I suspect we are going to get a lot of really good ideas on how to refine or modify these bookends we put on the table,” Beaudreau said during a news conference to unveil the draft proposals on Tuesday at Hoover Dam.

Federal officials say the steep cuts are needed to prevent the river’s two main reservoirs from falling to points that would jeopardize hydropower generation and water delivery to tens of millions of Americans in the Southwest.

Lake Mead, the river’s largest reservoir, has seen its water levels plummet amid 23 years of drought and chronic overuse and now sits at just over one-quarter full. The reservoir is expected to fall another 27 feet by the end of 2024, according to the latest projections from the Bureau of Reclamation.

Southern Nevada, which gets about 90 percent of its water from the Colorado River, has worked to reduce its consumptive use over the last several decades, and in 2022 consumed less than three-quarters of its typical 300,000 acre-foot annual allocation.

But under either scenario proposed Tuesday, Nevada’s share of the Colorado River would be cut dramatically, especially if Lake Mead were to fall below 1,000 feet in elevation.

Ongoing negotiations

John Entsminger, general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority and Nevada’s lead negotiator on the river, said after the news conference that he had not had a chance to review the 476-page draft from the federal government, which was released minutes before the announcement. But Entsminger said Las Vegas is well positioned to handle any potential cuts.

“I firmly believe that as long as this community continues to implement our conservation plan, then we’re going to be OK under any circumstances,” Entsminger said.

The negotiations between the states have been ongoing, Entsminger said. Having the draft proposals now out on the table essentially lays out the tools that the federal government believes they have at their disposal to implement these cuts, which Entsminger said should further spur those negotiations.

In January, the seven states that rely upon the Colorado River submitted competing proposals that trended along similar lines to the proposals laid out Tuesday by the Interior officials, with California sticking to strict priority rights and the six other states jointly proposing cuts spread across the lower basin. California has some of the oldest and most senior water rights along the river, which under the priority system means it would be last in line to take cuts.

John Fleck, a water researcher at the Utton Center at University of New Mexico School of Law, said that by putting both alternatives on the table, the federal government can now take on the question of what it would mean to allocate water based on the strict priority system compared with sharing that burden in a more proportional way across the basin.

“For the last 15 years on the Colorado River in the lower basin, we have avoided the fundamental conflict between California’s insistence on protecting its priority rights and the desire of others, especially Arizona, to more equitably share the burden of the impact of climate change,” Fleck said Tuesday. “The way we’ve avoided taking on that fundamental question of which way to manage the river is by avoiding and draining the reservoirs. We can’t do that anymore.”

‘Reinvigorated sense of collaboration’

The two draft proposals also represent some strategic maneuvering on the part of the federal government, said Elizabeth Koebele, an associate professor at University of Nevada, Reno who studies water policy and governance.

She said the second alternative that calls for an equal percentage of cuts among the lower basin states is Interior laying out a “worst-case scenario” for California, essentially giving California a baseline from which it can negotiate.

“This provides a renewed foundation for the states to get together and really talk some numbers,” Koebele said. “It also gives California some political cover in some sense. Anything more than the proportional share is a win.”

This year’s snowpack in the Upper Colorado River Basin is one of the largest in nearly three decades, and forecasters expect snowmelt into Lake Powell this spring and summer to be the highest since 2011.

But even with those promising forecasts for this year, the outlook for the river and its two major reservoirs remains grim, showing that even one great snow year won’t be nearly enough to offset two-plus decades of drought and chronic overuse along the river.

“We’ve had good precipitation years during this 23-year drought. And yet the downward trajectory of this system has worsened,” Beaudreau, from the Department of Interior, noted. “We cannot kick the can on finding solutions.”

The promising winter snowpack appears to have lessened the need for the most extreme cuts that federal officials had been discussing since first broaching the need for emergency cuts last summer.

Both proposals laid out Tuesday call for cuts that are more modest than either plan submitted by the basin states in January. J.B. Hamby, chairman of the Colorado River Board of California, attributed that to this year’s better-than-anticipated snow season coupled with additional funding from the Biden Administration’s Inflation Reduction Act.

Hamby said the seven basin states are still working toward a full seven-state consensus, and he hopes that can happen in the next 45 days. Those conversations have seen a “reinvigorated sense of collaboration” since the public split between the states in January, he added.

“It’s better to have certainty about things you agree to rather than the uncertainty of things that could be imposed,” Hamby said.

Contact Colton Lochhead at clochhead@reviewjournal.com. Follow @ColtonLochhead on Twitter.