Westside School alumni chronicle history via book

The phone doesn’t stop ringing at Brenda Williams’ house.

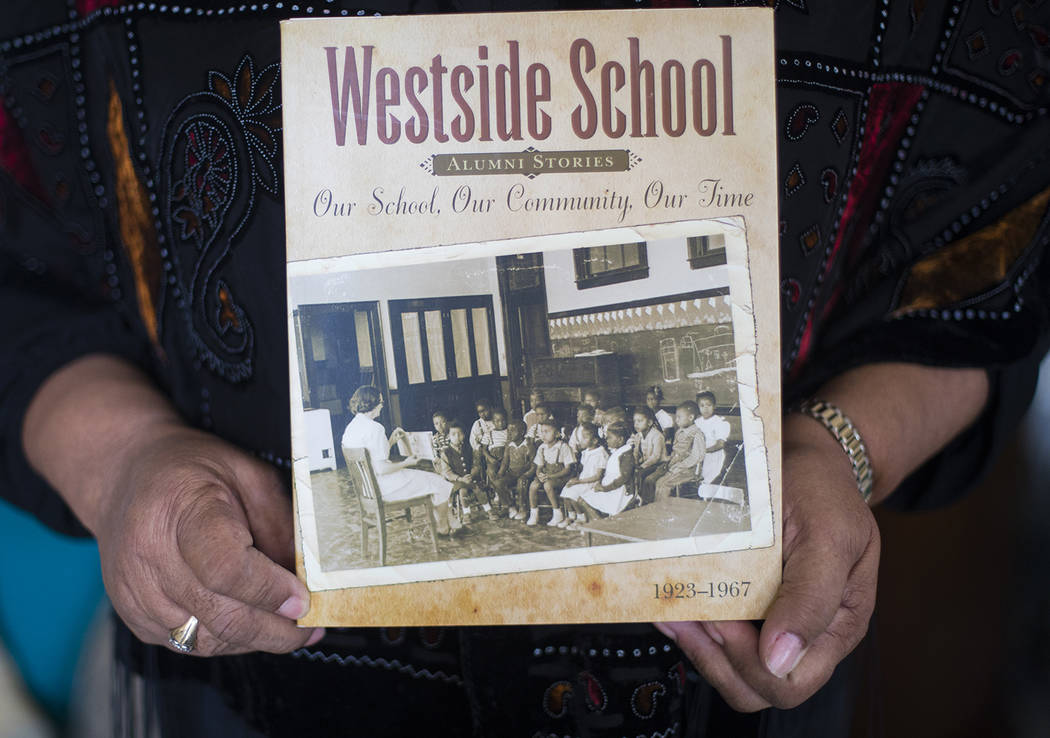

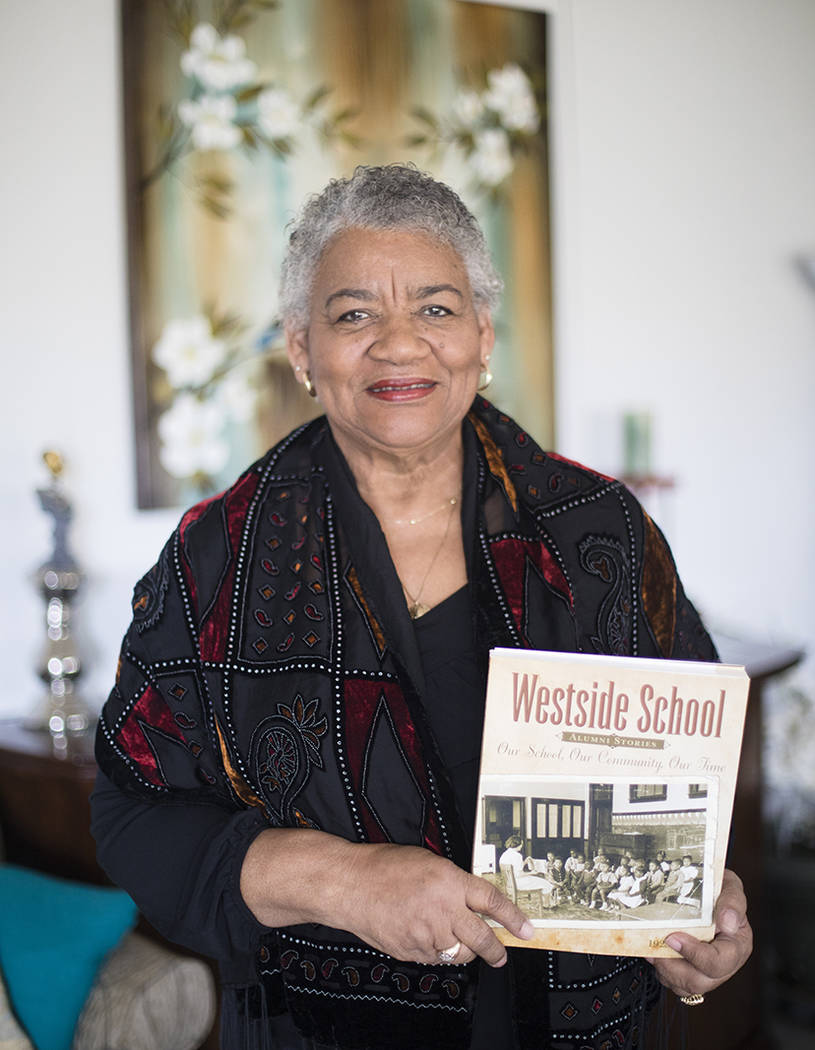

This particular day, people were calling to get their hands on a piece of local history: “Westside School Alumni Stories: Our School, Our Community, Our Time.” The Westside School was the first opened in the predominantly African American neighborhood, in 1923, and was a center for the community.

The book was put together by the Westside School Alumni Foundation from Clark County School District archives, personal collections and testimonials from former students. Williams, who is the president, sells them from her house, and the proceeds support the organization.

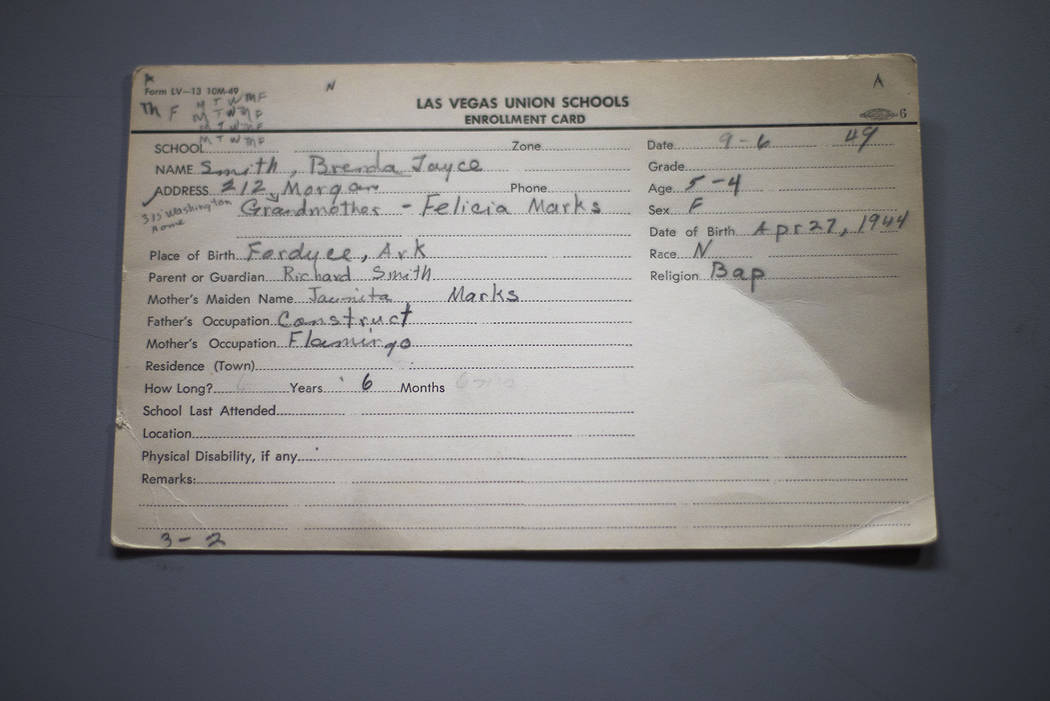

“We were trying to get people to tell the story they lived,” Williams said. She enrolled in the school in 1949 and remembers her parents stressed the importance of a good education.

In fact, a report card she still has from the fourth grade has nearly all A’s and one B-plus.

The hard work paid off.

In 1963, she made history by becoming the first African American to work as a bank teller in Nevada. In 1966, she broke another racial barrier at the Nevada Department of Motor Vehicles. Other alumni in the book were also the first African Americans in a number of occupations and positions in Nevada, Williams added.

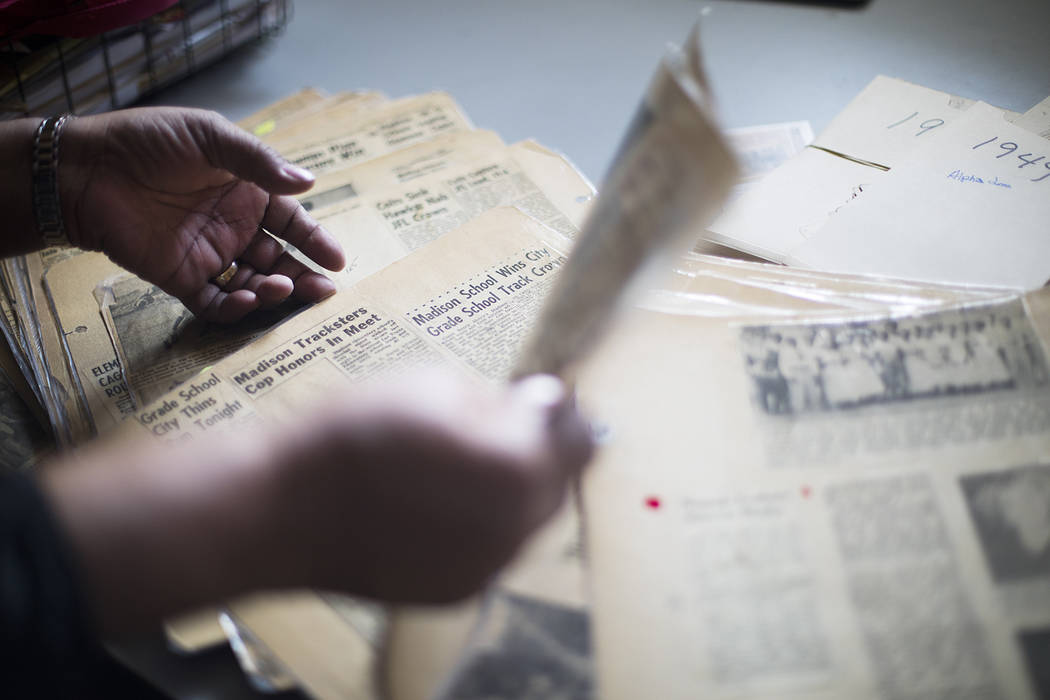

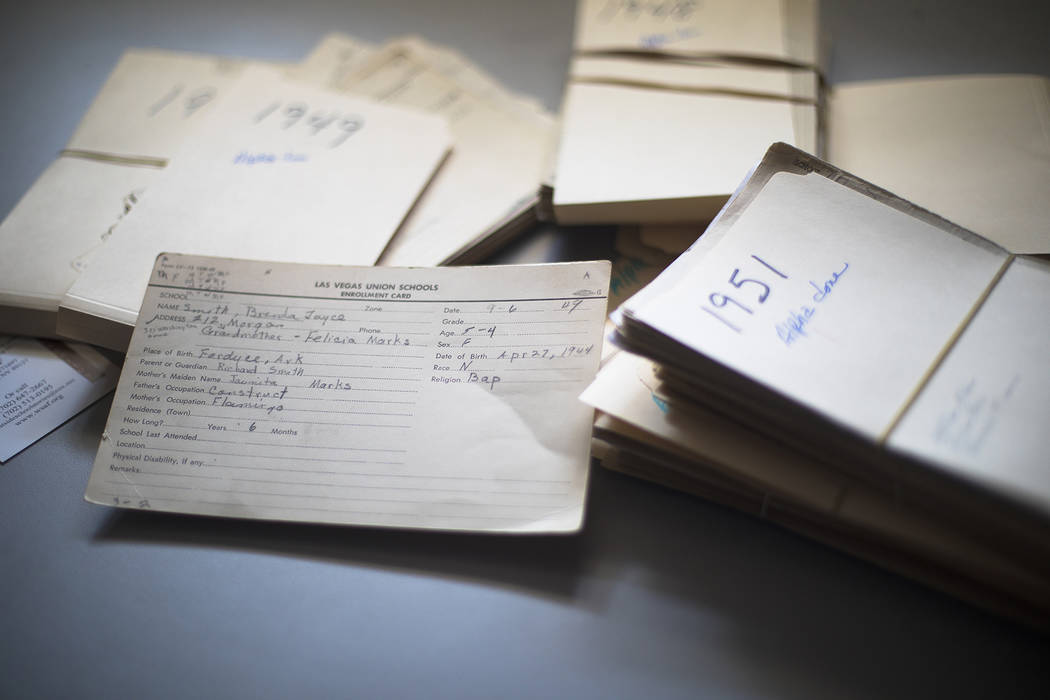

Thumbing through a stack full of laminated newspaper clippings and enrollment cards, she recalled a bygone era — “a time when everyone knew everyone.”

The Westside School operated until 1967 and served Paiute Indians, Latinos and white students during its earliest years, according to the book, which also includes testimonials from Latino students. In the 1920s, African American students started attending. Many of their parents moved to the valley for better jobs to “escape the poverty and bigotry of the South.”

Westside neighborhood was known by its name because it was west of the railroad tracks, according to Dr. Kay Carl, a former teacher and member of the CCSD Archives Committee. There weren’t adequate grocery or drugstores, and many of the roads were unpaved.

“It was a tightknit community,” said Carl. “Those people who were in that book were the ones that formed that community. Segregation was deep, and they are to be admired for the fact that they were able to pull together individuals to make up an actual community.”

In the 1960s, West Las Vegas schools had enrollments of more than 95 percent African American students. By 1966, seven elementary schools had opened in the Westside neighborhood to accommodate the growing population, according to the book.

Westside had expansions and taught students in kindergarten through eighth grade.

The school was a cultural center, recalled former student Lois Hodge. There were children from the South who had grown up on plantations, as well as those of Mexican and Paiute Indian decent.

For some black students, it was the first time they attended school in an integrated classroom.

Teaching

Flipping through the book, many alumni credit their success to one teacher in particular, Henry Moore.

His former pupils still call him Mr. Moore.

He died in 1996 at 85 and also taught at Madison Elementary School (renamed Wendall Williams), Hyde Park Junior High and Western High, according to his obituary.

He was a no-nonsense type of teacher, many alumni wrote in the book.

Moore wasn’t just strict with his students. He “demanded” parents be just as strict at home, said Otis Harris, who had him as a coach and eighth-grade teacher. If a student missed school, Moore would go to the student’s house and ask the parents why.

“He said once you get in trouble, trouble is always with you,” Harris said. Moore had a degree in chemistry with minors in math and physics. He moved to the valley to be a research chemist with the U.S. Bureau of Mines in Boulder City. In 1947, he became one of four black teachers in Clark County, according to the book.

Moore was remembered just as well for his commitments outside the classroom. He coached track, basketball and football.

“He invited all the kids to play sports because he thought it was a good thing to keep you out of trouble,” Harris said. “He was adamant about keeping kids out of trouble and focused on their education.”

Moore’s main goal was to get his students into college. Williams remembered he would teach eighth-grade students pre-algebra – something that wasn’t part of the school’s curriculum — so they wouldn’t struggle with algebra the next year.

“He prepared them for that,” Williams said. “He was a catalyst of their success.”

His effect was so strong, a group of Westside alumni are pushing to name a school after him. That group includes Williams and Harris.

“He’s one of the few people that anyone (who) was in his class, they were successful and disciplined,” Harris said. “You weren’t afraid of him; you loved him because you knew he cared for you.”

Contact Alex Chhith at achhith@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0290. Follow @alexchhith on Twitter.

About the book

Name: “Westside School Alumni Stories: Our School, Our Community, Our Time”

Publisher: The Westside School Alumni Foundation, which asked for testimonials and found documents from achieves and personal collections

Includes: Photographs, report cards, letters, newspaper clippings and attendance cards and certificates

Completion time: One year

How to purchase

The book costs $35; email westsideschoolstories@cox.net.