Residents of ‘sinking’ North Las Vegas neighborhood await promised funds for new homes

For Eli Valdez, 2019 was a “very happy time,” he said. He had become a first-time homeowner and gotten married. But not long after buying his first home in Windsor Park, a neighborhood in North Las Vegas, Valdez said things “just started to go wrong.”

The door to Valdez’s home had to be replaced because it wasn’t fitting correctly in the doorway. And sitting in his living room, Valdez said he could see that his house had become slanted.

These are the same concerns residents living in the neighborhood, which is sinking into the ground because of geological faults, have been raising for decades. A Review-Journal article published in 1988 reported residents complained of “years of sloping floors, cracking walls and ceilings, jammed doors and sinking yards as the ground around them mysteriously caves in.”

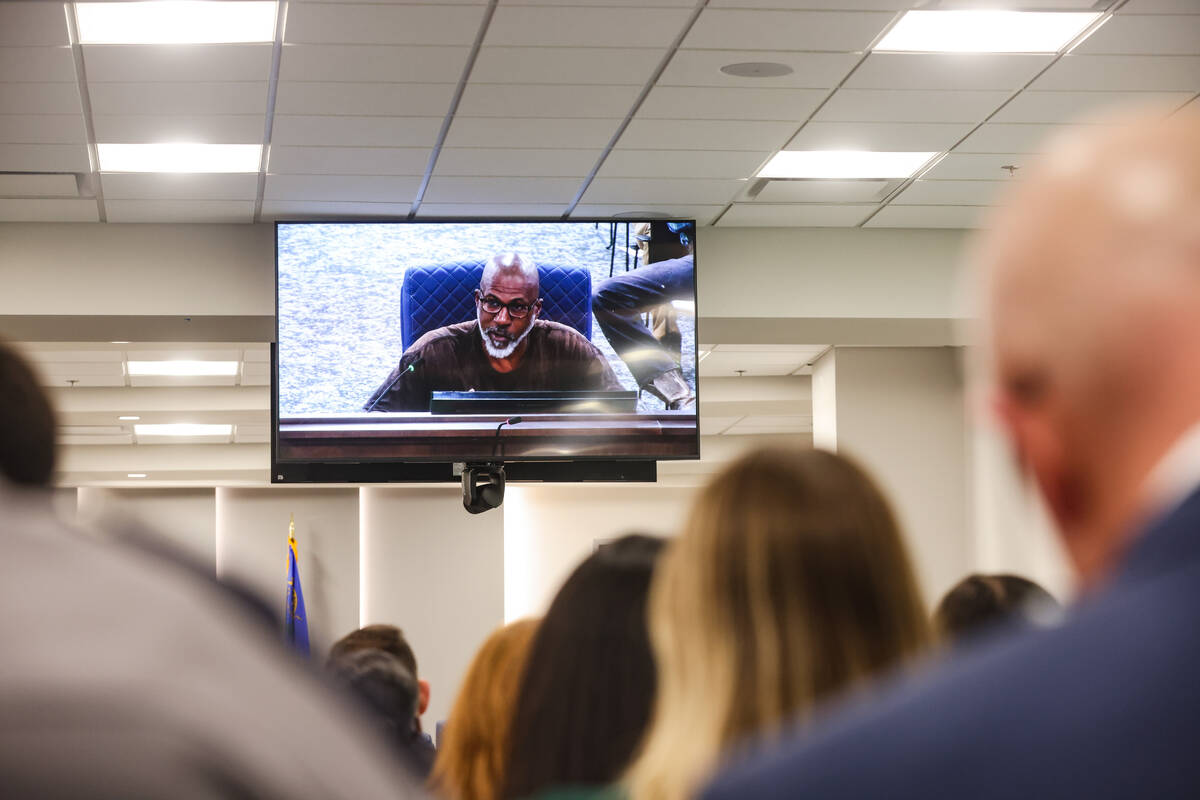

Barbara Carter, a resident of the historically Black neighborhood, said she and her husband bought their house in 1966. “We had dreams, plans that this is something that we would leave to our children. But now this dream is dead,” Carter said in a public comment made in a meeting Thursday of the state’s Interim Finance Committee.

A law enacted in 2023 offering Windsor Park residents a light at the end of the decades-long tunnel was on the agenda, and dozens of residents shared a bus to the Nevada Legislature Office on Amigo Street to, once again, convey their pain to public officials.

“The original residents of Windsor Park, predominantly Black families, have endured decades of neglect, broken promises and systemic racism,” Jollina Walker, state policy director for Make It Work Nevada, told the committee.

“It is not lost on me that this community is predominantly Black. Think about that for a second,” said Candese Charles, communications coordinator for the Sierra Club Toiyabe Chapter, in the meeting.

Senate bill that promised funds

In 2023, the Legislature passed a bill that made $37 million available to purchase nearby private land and offer residents new homes. But more than a year out from the bill being passed, none of the $37 million has been spent, officials said in Thursday’s meeting.

Steve Aichroth, administrator for the Nevada Housing Division, and Christine Hess, the division’s chief financial officer, appeared before the committee to discuss progress made on their program, empowered by Senate Bill 450, to build homes for impacted residents. But rather than spending the funds obligated by the bill, Aichroth and Hess asked the committee to consider an alternative proposal by Gov. Joe Lombardo.

Of the $37 million, $12 million comes from a state housing fund paid for by the city of North Las Vegas. The other $25 million comes from COVID-19 relief funds. Lombardo proposed a change in the funding source for the $25 million, urging legislators to consider reallocating the money and using state general funds instead.

As prescribed by Senate Bill 450, all $37 million must be expensed by Dec. 31, 2026. It’s a deadline that Aichroth and Hess said is looking difficult to meet, as plots of land for 93 new homes need to be secured.

“The proposal to change funding streams for the project secures funding for Windsor Park, instead of leaving it susceptible to change due to federal guidelines,” said Elizabeth Ray, spokesperson for Lombardo. “This proposal guarantees the future of the Windsor Park community.”

But Assemblywoman Daniele Monroe-Moreno, chairperson of the committee, said that de-obligating the funds isn’t so simple and would leave residents without guaranteed funding.

“A promise was made to these families,” she said. Changing the funding stream would mean “there’s no guarantee to those families, or to your division, that the next legislative body would agree to the replacement of that $25 million from the general fund,” Monroe-Moreno said.

While Aichroth and Hess said the complexity of the project means that the Nevada Housing Division is potentially “going to miss the mark,” state Sen. Nicole Cannizzaro told division officials, “We just have to find a way to do this.”

“We can’t just be another place where their pleas have fallen on deaf ears,” Cannizzaro said.

Life in Windsor Park

As Windsor Park residents try to repair their sinking homes, new neighbors moved in: warehouses. The construction of a commerce park in 2023 worsened existing issues and created new ones, residents said. “They are cutting ribbons all around us, but there are no cutting ribbons for Windsor Park residents,” said Nancy Johnson, who moved to the neighborhood in 1966.

When construction began on the warehouses, Carter said her walls and ceiling started cracking. For Valdez, the problems he experienced before the construction worsened. “I thought my house was going to fall,” he said.

Nasir Abed said he moved to the U.S. from Afghanistan in 1986 to pursue his American dream of buying a house and having a family. Today, Abed, another Windsor Park homeowner, said his 5-year-old-son prays every day that their house doesn’t fall and kill his family.

“We shouldn’t have to live like that. We paid our taxes. We worked all our lives,” Johnson said. “It doesn’t make any sense. The money is there. Let us use it to build a new home.”

“We deserve that. We matter, we do,” Johnson said. “We are human beings.”

Contact Estelle Atkinson at eatkinson@reviewjournal.com. Follow @estellelilym on X and @estelleatkinsonreports on Instagram.