UNLV professor examines Lincoln’s relationship with Native Americans

It’s risky business, messing with the memory of Abraham Lincoln. For some, our 16th president is a secular saint, revered for ending slavery and guiding the nation through the Civil War and becoming not just a paragon of virtue to generations of American schoolchildren but co-honoree of a national holiday that arrives in just a few weeks.

Michael Green knows it. There’s an aphorism that the three most written-about figures in history are Jesus, Shakespeare and Lincoln, Green says, “and one reason, I think, is there’s so little source material to work from.”

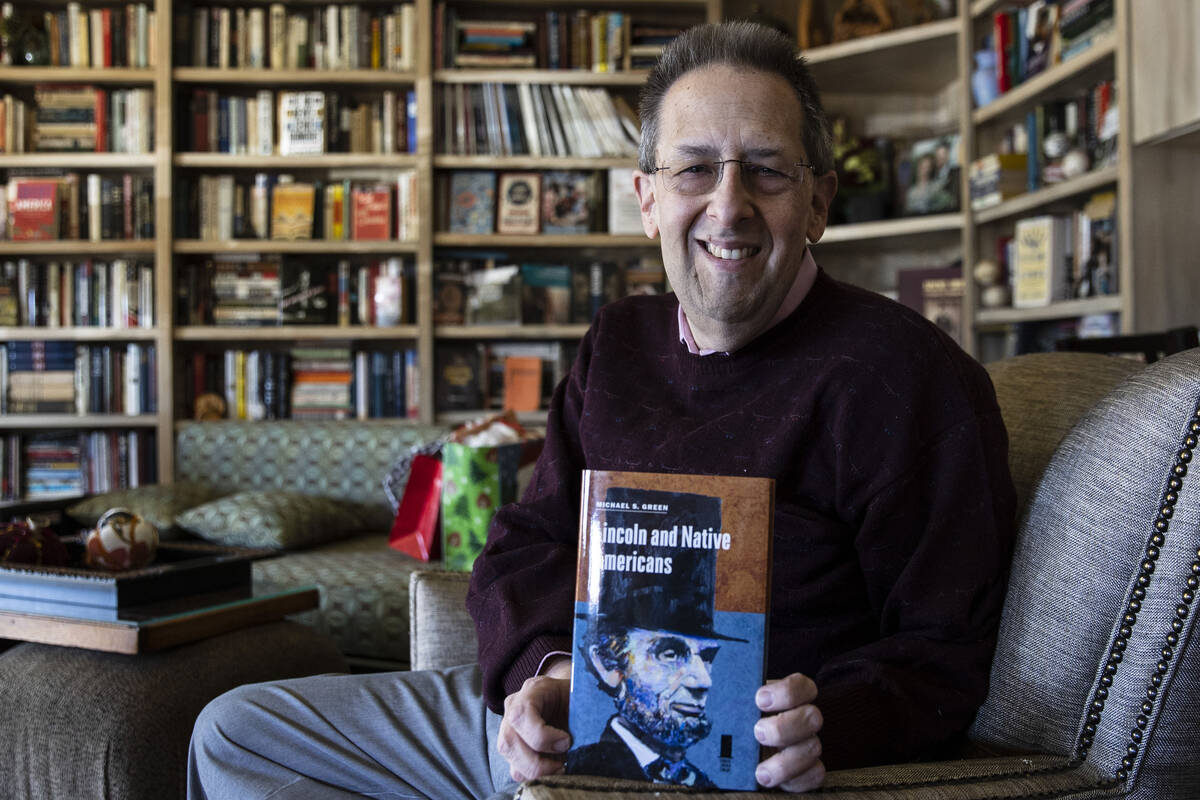

Green, an associate professor of history at UNLV, recently added to the body of Lincoln literature with “Lincoln and Native Americans” ($24.95, Southern Illinois University Press), which examines Lincoln’s actions regarding, and his own views about, Native Americans.

His general judgment: Lincoln was not as perfect as some might have hoped but better than most others of his time, although he showed relatively little interest in the entire topic even before slavery and the Civil War came to become his main concerns.

Fittingly, and if Presidents Day presents are a thing, Green will read excerpts from and sign his book at 7 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 3 at The Writers Block, 519 S. Sixth St. For more information, call 702-550-6399.

A different perspective

The book is part of a series called “The Concise Lincoln Library,” made up of “short, and ideally readable, books about various aspects of Lincoln’s life,” says Green, who previously had written an entry in the series about Lincoln and the election of 1860.

When Green was approached about writing about Lincoln and Native Americans, it meshed with his bucket-list desire —“historians have them, too,” he says — to write a book about Lincoln and the West.

Examining Lincoln’s relationship with Native Americans isn’t a topic that’s been explored extensively, Green says. “Certainly there’s been a revolution — I don’t think that’s exaggerating the term — in historical writing in my lifetime, and I’m going on 57, where historians increasingly have turned to women and people of color and groups earlier generations didn’t pay enough attention to or paid no attention to,” he says.

Also Lincoln’s actions regarding Native Americans don’t immediately come to mind for most Americans, whose history classes tended to cite the Civil War, politics, the military and slavery, “not necessarily in that order,” Green says, as the driving forces in Lincoln’s presidency.

Lincoln’s personal background adds a particularly intriguing layer to the discussion. His grandfather was killed by Native Americans on the Kentucky frontier who were upset about white encroachment on their land, fomenting hatred of Native Americans among some family members. Lincoln also served in the militia, Green says, joking later about his “undistinguished service” but taking great pride in it.

An evolving view

In his book, Green examines the opposing ways in which Lincoln regarded Native Americans and African Americans.

“There is a tendency among some who love Lincoln to feel he started out perfect and got better,” Green says. “No. There’s a lot to admire, and there are things we won’t admire, and there are things to admire but it’s hard to understand them.”

“We don’t find him expressing a lot of prejudice,” Green says. Yet Lincoln moved from saying he’d save slavery if it would preserve the Union to supporting the abolition of slavery because he believed it jeopardized the Union, and later advocated that some African Americans should have the vote.

“This is a significant step,” Green says. “He had moved, I think we’d believe, in the right direction a long way in a very short time.”

In the case of Native Americans, “he doesn’t have the same growth, and that may be in part because he had fewer encounters and less experience or exposure, if you will (to Native Americans),” Green says. “But you also see early in his life that he’s not Andrew Jackson. He isn’t out to kill.”

For example, during his military service in the Black Hawk War, “when his men wanted to kill an elderly Native American who came into camp with a letter of passage, Lincoln wants to protect this guy,” Green says. “You don’t find in him the hatred that it inspires in other people, including members of his own family.”

On the other hand, Lincoln mostly “didn’t think about Native Americans,” Green says. As president, “politics, the military and slavery were his main concerns. If this is a Billboard chart, Native Americans are not in the Top 10.”

“There are Native Americans, in Oklahoma in particular, (who) he left hanging out to dry while he was involved in other things. He allowed the military to abuse and kill Native Americans, particularly in the far West. He can be condemned for those things, but he was not unique in not paying the attention he should have paid.”

A curious fact

The 1862 Dakota Sioux uprising in Minnesota provides fodder for a fascinating bit of historical trivia that illustrates Lincoln’s lukewarm relationship with Native Americans: Which U.S. president, according to Green, ordered both the largest mass execution of indigenous people in American history and the largest commutation of executions in American history?

The answer, according to Green: Lincoln, for the very same incident.

After the 1862 Dakota Sioux uprising in Minnesota, a military tribunal ordered the deaths of more than 300 members of the Dakota tribe. “Lincoln says hold it, and has files sent to three lawyers in the Interior department,” Green says. “They read 303 files. He says, ‘I want anyone who committed war crimes, who violated a dead body or violated a woman, to be executed.’ They winnowed it down to 38. He dictated the wire listing who would be executed, including spelling out the names if there was another Dakota Sioux with (a similar or the same) name.”

Ultimately, Lincoln ordered the deaths of 38 but commuted the death sentences of 264. Ordering the executions “was terrible,” Green says. “It was wrong.”

Then, after the 1864 election, Lincoln told a Minnesota congressman that he had received a smaller electoral majority in Minnesota than he had in 1860. The congressman replied that Lincoln’s majority would have been larger if he hadn’t issued so many commutations. Lincoln, Green writes, “replied, ‘I could not afford to hang men for votes.’

“To me, this stamps him as at least better than a lot of others in his time. But we still like him to be the Lincoln who said we’re going to end slavery and have women’s suffrage. That isn’t him. I believe he believed in trying to improve Native Americans’ lives, but part of the problem is that there are even those who believed strongly in reform who didn’t agree.”

Ultimately, “it’s a nuanced story,” Green says, “which I think, frankly, all of history is.”

In examining Lincoln’s dealings with Native Americans, “we realize his faults,” Green says. “There was certainly more he could have done. And I think we learn more about his humanity, because he still did more than I think others would have done or could have done.”

And with this mixed bag of faults and merits, Green says, the story of Lincoln and Native Americans offers the chance to “maybe see him a little more fully.”

Contact John Przybys at reviewjournal.com. or 702-383-0280. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.,