Youth camp’s forestry program marks 52 years at Mount Charleston

Since 1970, trail maintenance at Mount Charleston has been bolstered every summer by dozens of helping hands from a juvenile detention center.

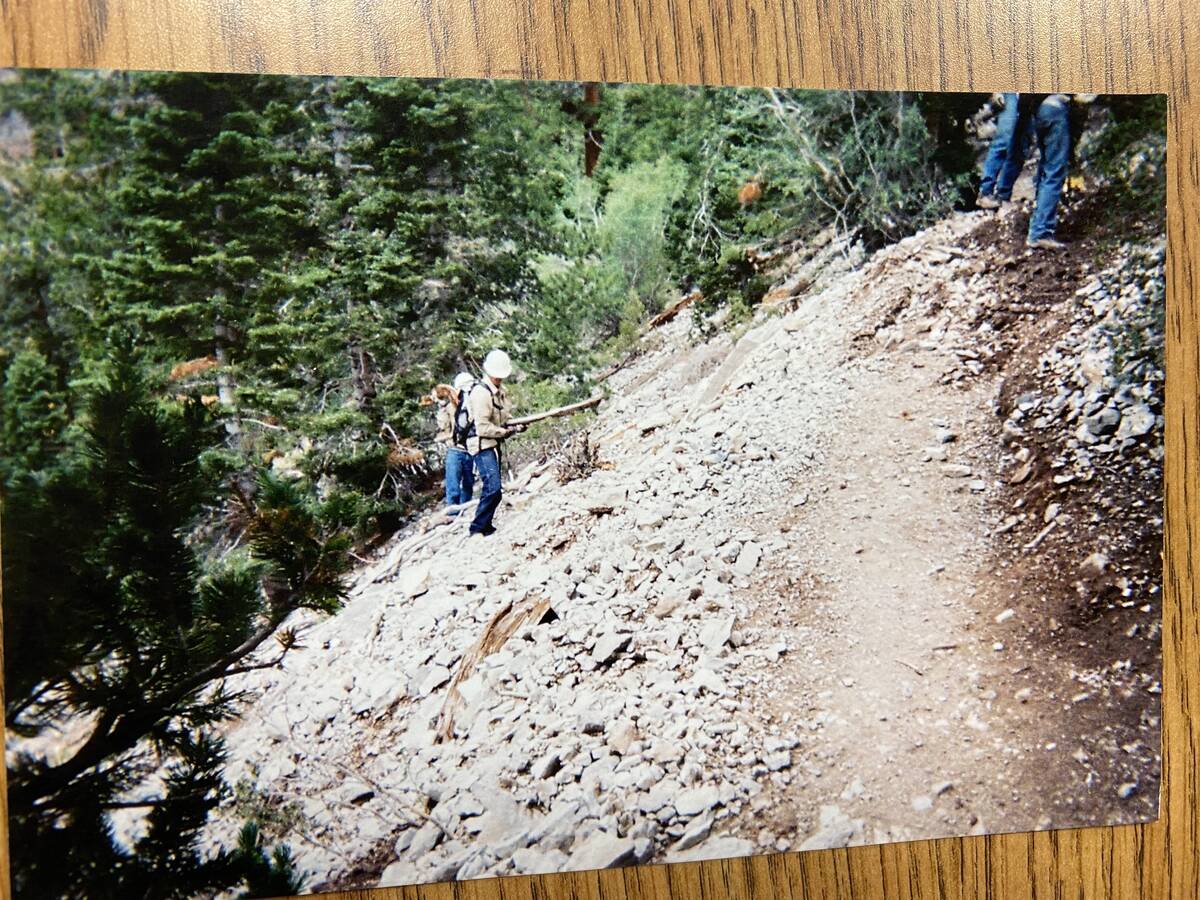

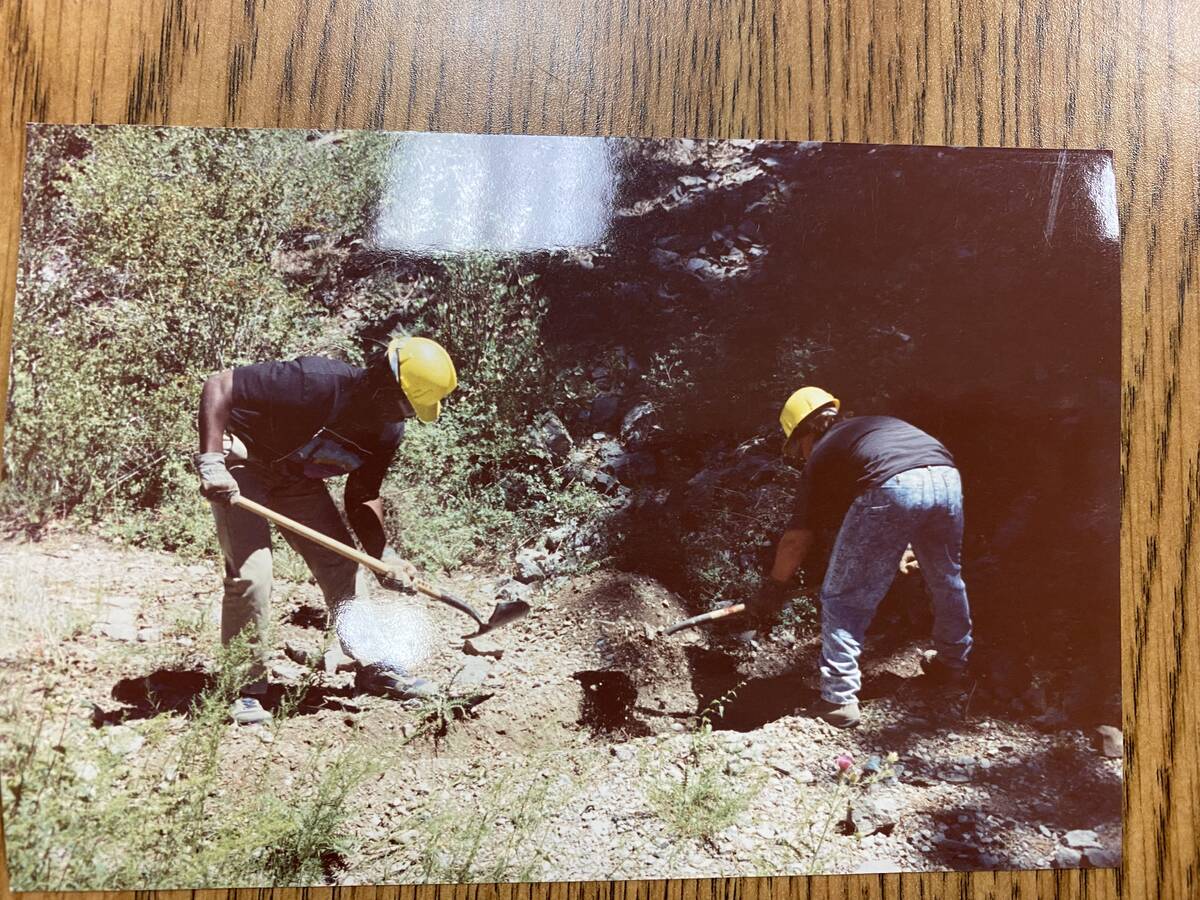

Boys serving time at Spring Mountain Youth Camp have filled that role through one of the longest interagency partnerships in the history of the U.S. Forest Service. Their work can include trail assessment and management, fire ring removal, trash removal and constructing rock walls or stairs.

Wednesday was the last day of the 52nd year the camp partnered with the Forest Service for a nine-week forestry program.

“With those kids, you got a couple crews of 10 kids, they can do a lot of things,” said Larry Benham, who retired in 2015 as a forest ranger after working for the Forest Service since 1968. “A lot of it wasn’t chainsaw work and stuff like that, but it was work that just took bodies and numbers. … They saved us a lot of time and effort because it wouldn’t have gotten done if they hadn’t been there.”

The detention center at Mount Charleston currently houses about 60 boys 13 and older. On Wednesday afternoon, a group of boys was playing cornhole on a turf field. Nearby, others played basketball on the camp’s courts.

Down the road that leads to the camp’s main office is a football field where the Spring Mountain High School football team plays every fall.

Kelly Storla, juvenile probation supervisor for Clark County, which operates the camp, said every boy has the opportunity to apply for the forestry program, which Storla also supervises. The boys earn money for their work that can go toward paying restitution to victims.

“They have to treat it like a job; they have to be prepared with all their safety equipment,” Storla said. “We provide them with everything.”

School first

The program starts every June with a week of training for the camp staff followed by training for the boys who apply to the program.

“We physically condition them to get them ready,” Storla said.

Boys work Monday to Thursday and start each day with two summer school classes. Then they are directed by the Forest Service to work on whatever tasks are needed for that day. This year, 32 boys took part in the forestry program.

The camp is operating at a reduced capacity because of staff vacancies that have to be filled before two more dorms can open, according to Storla. A normal year has about 50 boys in the program and a camp capacity of 100.

Participants in the program also earn points for their work and behavior that can go toward credit for an earlier release or special privileges such as video game time or buying snacks.

“It’s positive reinforcement that we use to encourage kids to do the right thing,” camp manager Cesar Lemos said.

Storla said being in a work program gives the boys a better chance of maxing out the number of points they can earn in a day.

Wednesday was the last day at the camp for a boy who was named this summer’s forester of the year. He spent six months at Spring Mountain and said he applied to join the forestry program because had experience in construction and landscaping. The Review-Journal is not publishing his name.

“I thought it would be cool to be able to put that work and skills into action,” he said in a phone interview.

He described working on trails and building a rock wall. He called the program “phenomenal.”

“I learned how to build trust with my peers, with the POs (probation officers) there, and I also learned to be honest,” he said.

Now that he’s back home, his goal is to work and make enough money to get into community college and then a university. He said he’s interested in pursuing mechanical or electrical engineering.

“The atmosphere with the kids and with the POs, it’s a friendly vibe,” he said of the camp. “Everybody gets to know each other for a while and we all build a bond.”

Juvenile justice system

District Judge David Gibson Jr. sends minors to the camp after they have exhausted resources available to them at home.

Many kids sent to the camp have stolen cars or assaulted people. Gibson said some of them are products of broken-home environments.

“The background of the juvenile justice system in the United States at its root is an acknowledgement that the individuals that are involved in what we call delinquent behavior are kids,” he said. “That they don’t have adult capacities to understand completely the consequences of their actions.”

The goal of the system is rehabilitation, rather than punishment, that weighs public safety and the best interest of children.

“It’s just a practical recognition from the people who write the laws that some of these kids didn’t start at the same starting line as others,” Gibson said. “And instead of just throwing them into prison, instead of just treating them like a criminal, let’s at least take a chance and try to make them productive.”

The camp is the middle ground between formal probation and being confined by the state, according to Gibson.

“It’s almost like they’re at home on formal probation, except they’ve been removed out of our community,” he said.

The camp is less restrictive than being committed to state confinement run by the Division of Child and Family Services.

Gibson said the average stay at the camp for a minor is five to six months. Some can go home in four or five months, but if a resident is there for closer to eight months, the camp typically will ask the court to commit the minor to the state.

He said the majority of boys who come back from Spring Mountain are less of a risk to the community because of their experience at the camp.

Mutually beneficial

Ray Johnson, fire prevention officer with the Forest Service, said the partnership benefits not only the camp and the agency, but also visitors.

Boys in the program help maintain more than 135 miles of trails in the Spring Mountains National Recreation Area, according to the program’s website.

He said the usage of trails by the public has exploded. The Mary Jane Falls Trail would have about 400-500 people per day on busy weekends 20 years ago, Johnson said. It’s now three times that on busy days, he estimated.

Storla said more than 1 million people visit the recreation area’s trail system every year.

More visitation means more problems, including trash and people causing more erosion by taking shortcuts off the main trail.

Johnson said keeping trails maintained makes it easier for emergency crews to maneuver them to fight fires and to reach hikers in need of medical attention.

“The real people who are benefiting is the public who uses the trails,” Johnson said. “So it’s kind of a three-way partnership. Anyway you look at it, it’s helping somebody.”

Contact David Wilson at dwilson@reviewjournal.com. Follow @davidwilson_RJ on Twitter.