Tougher academic requirements changing the game

Andy Johnson needed a point guard. The Findlay Prep boys basketball coach scoured the country this spring and ultimately zeroed in on a pass-first playmaker from Louisiana named Skylar Mays.

Johnson was first drawn to Mays' leadership, his innate ability to know when teammates needed a kick in the tail or an arm around their shoulder. And he loved Mays' poise.

"He plays with a great demeanor and just an even keel to him," Johnson said. "He's kind of an old-school, throwback point guard."

Still, it wasn't the way the 6-foot-4-inch senior dropped dimes in transition or put teammates in the proper spot on the court that ultimately convinced Johnson he found his point guard for the upcoming season.

It was Mays' high school transcript.

"I was really impressed," Johnson said.

Mays, who transferred to Findlay Prep in June from University Laboratory High in Baton Rouge, La., is part of the first senior class to play its entire high school career under a new set of NCAA initial eligibility requirements.

With the week-long early signing period for many sports set to begin today, the effects of those standards, which make it more difficult for student-athletes to earn a college scholarship, are being seen for the first time in the Las Vegas Valley and across the country.

"Freshman year, I was kind of just excited being in high school, just being a normal kid. So I wasn't really reading into the academic requirements for something four years ahead," Mays said. "But Mom, she's always been on top of me. ... She's big on me understanding what it takes to be eligible academically for the next level, which is what I aspire to do."

The new initial eligibility standards were adopted in October 2011 by the NCAA Division I Board of Directors and came at a time when the NCAA's model of amateurism was increasingly being challenged.

The stricter requirements originally were set to go into effect with the 2015 graduating class, but after receiving complaints from coaches associations and high school and college administrators that students had only three years to achieve the new standards, the NCAA board voted in April 2012 to begin with the 2016-17 academic year.

The most notable change is to the minimum grade-point average. To be eligible to compete as a freshman at a Division I school, student-athletes now are required to carry a minimum 2.3 GPA in their core classes, up from 2.0, in addition to a qualifying ACT or SAT score.

According to the NCAA's sliding scale, which was revised in 2013 after another round of criticism, a student-athlete with a 2.3 core GPA must have a minimum ACT sum score of 75 or 900 on the SAT to be a full qualifier. A student with a 2.5 core GPA, for example, needs a 68 ACT sum or 820 on the SAT.

Recruits with a core GPA between 2.0 and 2.299, regardless of a qualifying test score, now are classified as an "academic redshirt" by the NCAA and may practice but not compete during their freshman year.

Nevada Interscholastic Activities Association rules require student-athletes to maintain a minimum 2.0 GPA to be eligible to play sports. The NIAA Board of Control two years ago examined whether to raise its requirement in conjunction with the NCAA's new standards but did not take action, according to NIAA assistant director Donnie Nelson.

"It's a big difference," Bishop Gorman boys basketball coach Grant Rice said. "You could get Cs throughout your high school career and be eligible for high school sports, and then you come your senior year and find out, 'Uh oh, I'm not going to make it to college.'

"That's a shame, and I think that 2.3 GPA, it gives them a little wake-up call that, hey, just staying eligible for basketball or football or whatever sport you're playing is definitely not enough."

In addition to the GPA requirement, students also must complete 10 of their 16 core courses before their senior year of high school, with seven of the 10 classes being in English, math or science.

Those 10 courses are then "locked in" to a student's transcript and cannot be repeated in order to improve the core GPA.

"I don't think the changes are that drastic where if someone's on top of what they're trying to do — qualify academically from the time they get to high school till the end — I don't see it as being a big change," Clark boys basketball coach Chad Beeten said. "What it will alleviate is last-minute type of trying to qualify and squeezing everything in at the end.

"We always try to counsel our kids that you can't wait till the last minute. If you do, it's just going to make you that much less appealing to any type of school that might be recruiting them."

While the increased GPA appears to be the most severe change, many believe it is the mandatory completion of 10 core classes before the start of their seventh semester that will trip up prospects.

The "10 by 7" requirement is intended to prevent students from scrambling to make up classes or taking cushy online courses to fulfill academic requirements in their final year of high school.

"I think with the way that society has changed over the last five, 10 years, I think an emphasis needs to be placed back on academics," Centennial girls basketball coach Karen Weitz said. "I think these kids are too much into their phones and all the social medias and all this technology that they've gotten away from what really helps them in life, and that's their academics."

'I see the truth. I see the struggles.'

The new standards apply to student-athletes in every sport. But critics such as the National Association for Coaching Equity and Development, a group of minority college basketball coaches formed this year and led by Texas Tech's Tubby Smith, Georgetown's John Thompson III and former Georgia Tech coach Paul Hewitt, believe the requirements disproportionately target men's basketball and football players.

According to a 2012 report by the NCAA, 43.1 percent of men's basketball players, 35.2 percent of football players and 15.3 percent of all Division I student-athletes who competed as freshman in 2009-10 would not have qualified under the new requirements.

"Without question, less kids are going to qualify," Beeten said.

The NCAA created a promotional campaign using slogans such as "2.3 or take a knee" along with a website (2point3.org) to publicize the impending changes.

But the disparities between Clark County School District schools and Las Vegas' transient nature often make it difficult to deliver the message, according to Desert Pines football coach Tico Rodriguez.

Students frequently transfer or come from out of state, and the new schools have no control over how students previously were being advised on their academics.

Coaching turnover also complicates efforts. Nine of the 20 Division I teams opened the prep football season with a new coach, and Cimarron-Memorial fired its coach after the opening week.

"You step on our campus at Centennial versus some of these other schools, I mean the difference is, honestly, night and day," Weitz said. "So, you are going to have a few (at-risk) kids that I think will slip through the cracks and then may struggle a little bit. That's kind of where you get the inequity, I think, even within our school district. ... With that being said, then that's up to the coaches to provide that extra support."

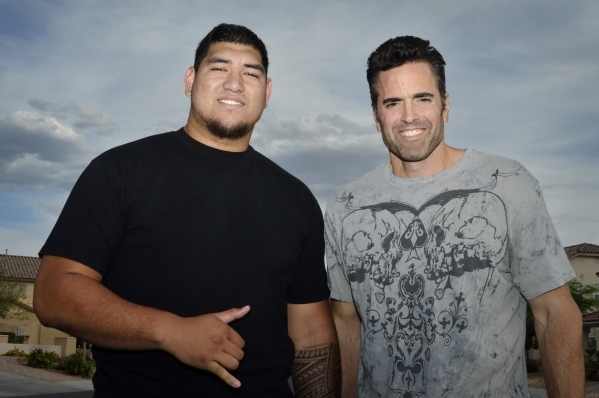

Rodriguez cited 2012 Desert Pines graduate Jeremiah Poutasi as an example of a player who would not have qualified under the new NCAA requirements. Poutasi struggled academically early in his high school career, Rodriguez said, before he earned a scholarship to Utah.

The offensive lineman started 10 games for the Utes as a true freshman and was selected in the third round of the 2015 NFL Draft by the Tennessee Titans.

"I don't like anything that penalizes a freshman that's still maturing," Rodriguez said. "You don't know the back story of a kid. I've got kids that have been homeless. I have kids whose parents are incarcerated. I see kids that have difficult situations. I see the truth. I see the struggles. I see kids that can't get to school.

"My thing is, I just want to help them. I want to get them to college. I want to give them an opportunity, and everybody has a different story and a different path. Not everybody is going to have the two parents and the stability, and I've seen it firsthand.

"I've seen great kids that started their career struggling, and then once they got stability with a program and they had mentors in their life, I saw them reach for the better. But when you don't give them an opportunity, that's just setting them up for failure, and I think we're here to help kids and not do them harm. You've just got to identify kids that need help earlier now."

'They want to minimize their risk'

The academic redshirt option could prove beneficial in the long run to many football players, as they are able to mature physically and acclimate to the rigors of college academics during their freshmen year.

For sports that rarely see athletes leave school early for the professional ranks, such as women's basketball, volleyball or soccer, the rule simply delays the start of their playing career.

All student-athletes in good academic standing at the conclusion of their academic redshirt year retain four years of eligibility under the new requirements, according to Eric Toliver, UNLV's associate athletics director for administration and compliance.

But the new eligibility requirements figure to have a major impact on elite athletes in other sports, especially baseball and boys basketball.

"I think it is different (for girls) only because what some of the top-level boys reach for, coming out of especially our city, and what the top-level girls out of our city, it's drastically different," Weitz said.

In the case of baseball, the new standards could alter a prep prospect's negotiating leverage heading into the Major League Baseball draft. For instance, a full qualifier will have much more bargaining power with the team that drafted him versus a player facing an academic redshirt year.

Boys basketball players expecting to go the "one-and-done" route now must have their academics in order to avoid sitting out as freshmen. Whether that means more players heading to junior college or playing overseas for a season before being eligible for the NBA Draft remains to be seen.

"How that's going to affect the next level and those kids, I don't know the answer," Beeten said. "Maybe in the long run it will strengthen (Division I men's basketball), and maybe it will hurt. It's just hard to tell."

Since 2010, Findlay Prep has produced six players who left after their freshman year of college and were taken in the first round of the NBA Draft. Johnson said the program, which is able to recruit unlike local public and private schools, will not waver on its commitment to only pursue players serious about their education.

Mays, who is set to sign with Louisiana State, is a full qualifier, as is Findlay Prep teammate and UNLV commit Carlos Johnson.

"Due to the new NCAA rules, there will be some student-athletes we might not be able to accept that we could in the past," said Andy Johnson, who is in his second year as the Pilots' coach after five seasons as an assistant. "Us being at a very good educational school, the Henderson International School, we try to take true student-athletes that want to succeed in the classroom first and realize if you want to play in our program, you're going to be a student first."

Rodriguez, whose squad is stocked with Division I recruits, already has noticed the impact of the new requirements as college coaches have visited Desert Pines this fall.

Instead of the first question being about a prospect's size or 40-yard dash time, recruiters ask for his ACT or SAT score.

"If he's not a qualifier, they're not going to waste their time," Rodriguez said. "I see that's the new trend. They want to minimize their risk, giving a kid a scholarship and he can't do the work and he's back in six months."

Mays knows that he is fortunate.

One of eight children, Mays comes from a family that emphasized the importance of academics. His hope is the NCAA's new initial eligiblity requirements will motivate younger athletes to pursue their education.

"At the end of the day, the percentages of college athletes making it to the pro level is very low," Mays said. "If you take care of what's going on in the classroom, then the chances of you getting a degree is very high. That's how I look at it. Unfortunately, not everyone has the resources to thrive in the classroom always. I honestly feel like it's very important guys strive to be better in the classroom and always strive to do their best."

— Contact reporter David Schoen at dschoen@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5203. Follow him on Twitter: @DavidSchoenLVRJ.