Declining Lake Powell water level sparks concern in Arizona town

PAGE, Ariz. — The signs of drought appear almost immediately on the way to Lake Powell’s Wahweap Bay.

Rocks that were once underwater now appear on the lake’s surface. A band of white on the canyon walls behind the Glen Canyon Dam marks where the lake level once reached.

People who are familiar with Lake Powell are not strangers to water level fluctuations. But this year, the lake level decline brought the country’s second-largest reservoir to a historic low, and with it, several challenges for those who manage the Colorado River and depend on Lake Powell for their livelihood.

“It’s really dramatic,” Heiji Klotzbach said of the decline this year. “You know, because before, when you’d look across here, this is all water.”

The 70-year-old Prescott, Arizona, resident looked out at the expanse of exposed rock from the top of Wahweap’s last remaining boat ramp, a steep grade he had to hike down to reach his family for a day on the water.

It’s up here that sits a sign of the most recent threat of a two-decade drought on the reservoir that straddles Northern Arizona and Southern Utah.

“No launching houseboats,” an electronic message board reads.

Economy ‘falling off the edge’

It’s that message that has forced Bill West to keep his inventory of houseboats away from the water. The boats now sit dry-docked in a yard behind his company’s office in Page, a small town that serves as a hub for Lake Powell tourism.

Since the last day he could launch in mid-July, West’s business, Laketime, which specializes in shared-ownership houseboats, has been missing out on an estimated $300,000 a week during his peak season, he said.

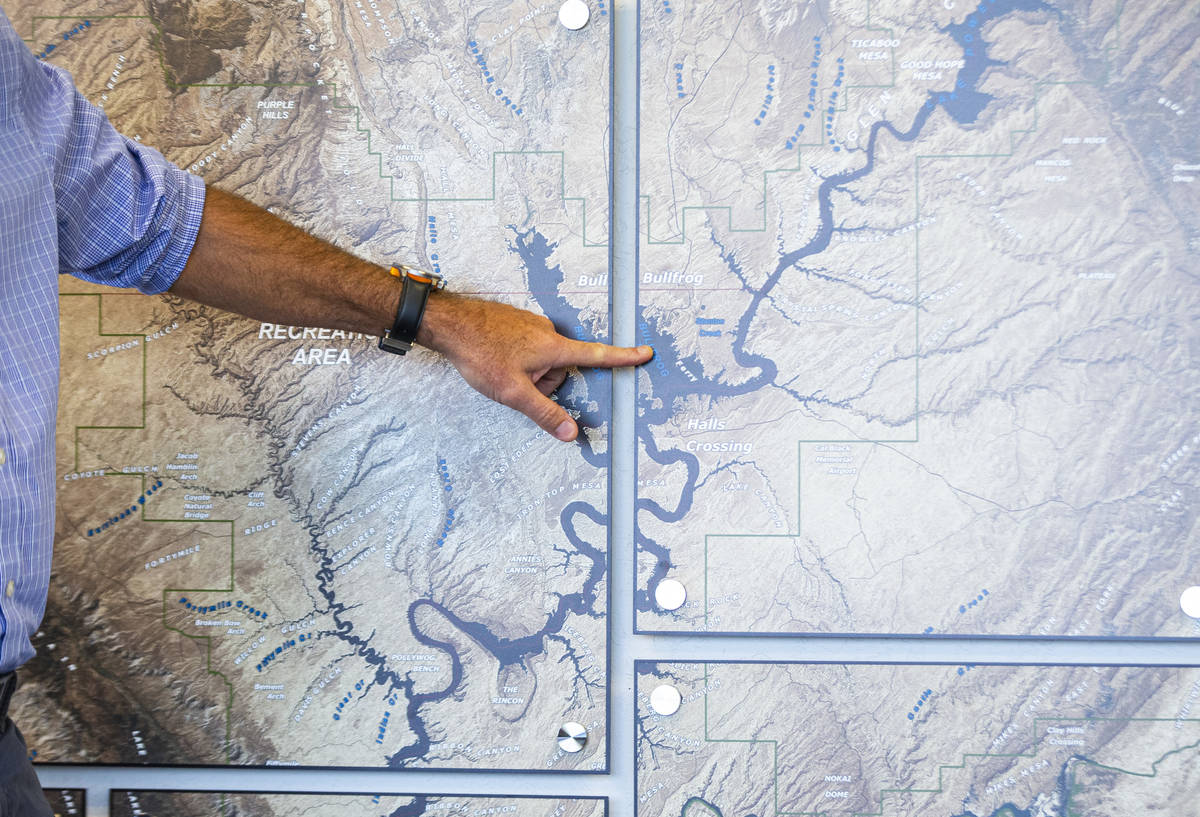

At its full elevation of about 3,700 feet, Lake Powell has 11 launch ramps. The lake now has only one fully functional ramp in Bullfrog Bay, about five hours away from Page.

In Wahweap Bay, the busiest visitor area, only one public ramp remains open, but large houseboats may not use it.

There’s still water here, but it’s getting harder to access it.

The water level is expected to drop to a level that would make the main launch ramp at Wahweap Bay completely unusable in about two weeks.

And maintaining access at Wahweap Bay is crucial for Page.

“The hotels, the restaurants, the grocery stores, the gas stations, everything depends on visitors going to the lake,” West said.

The National Park Service, which manages Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, said it is working on a permanent solution, but access to Wahweap Bay soon will be even more limited for boaters.

Even if a solution were to come quickly, Laketime would still take a hit because many who canceled their August trips cannot reschedule, co-owner Belinda Hunter said.

Randy Sherbrook, owner of the boat rental company Carl’s Marine Rentals, said Thursday that the uncertainty has led him to turn away reservations. The declining water levels, he said, are hitting Page hard.

“Our economy is falling off the edge as we speak,” he said.

Temporary solutions

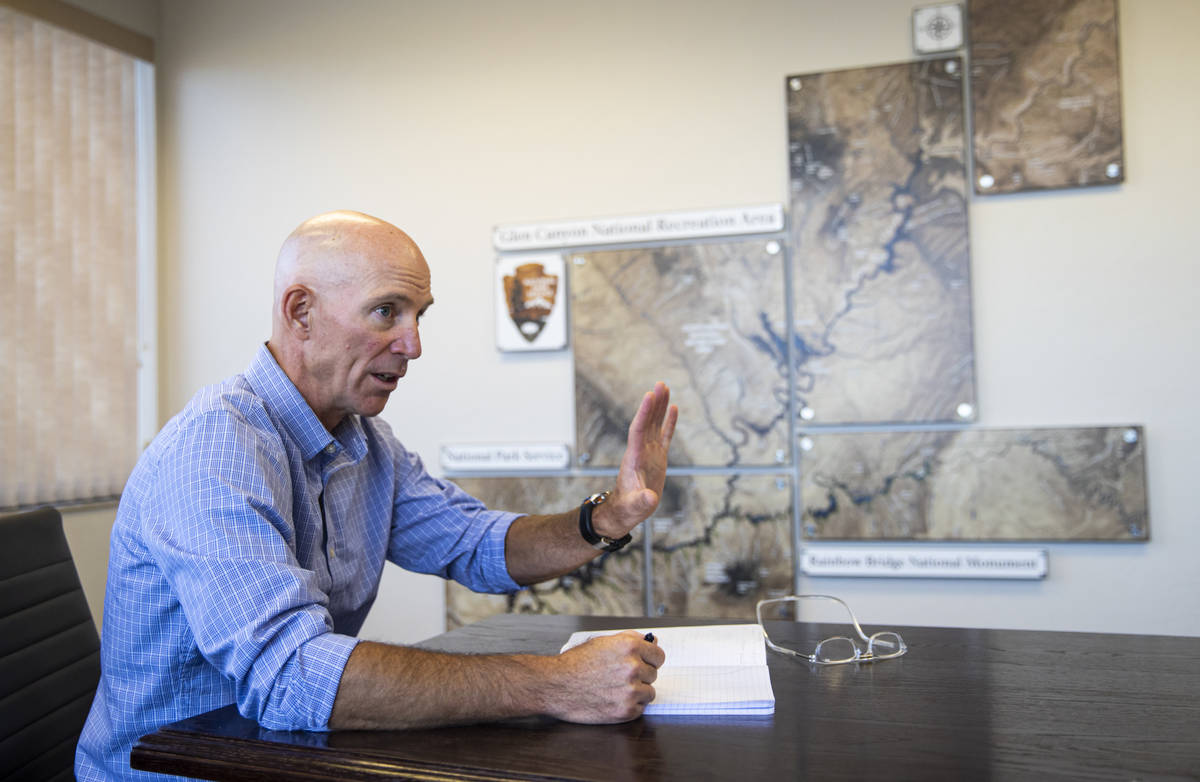

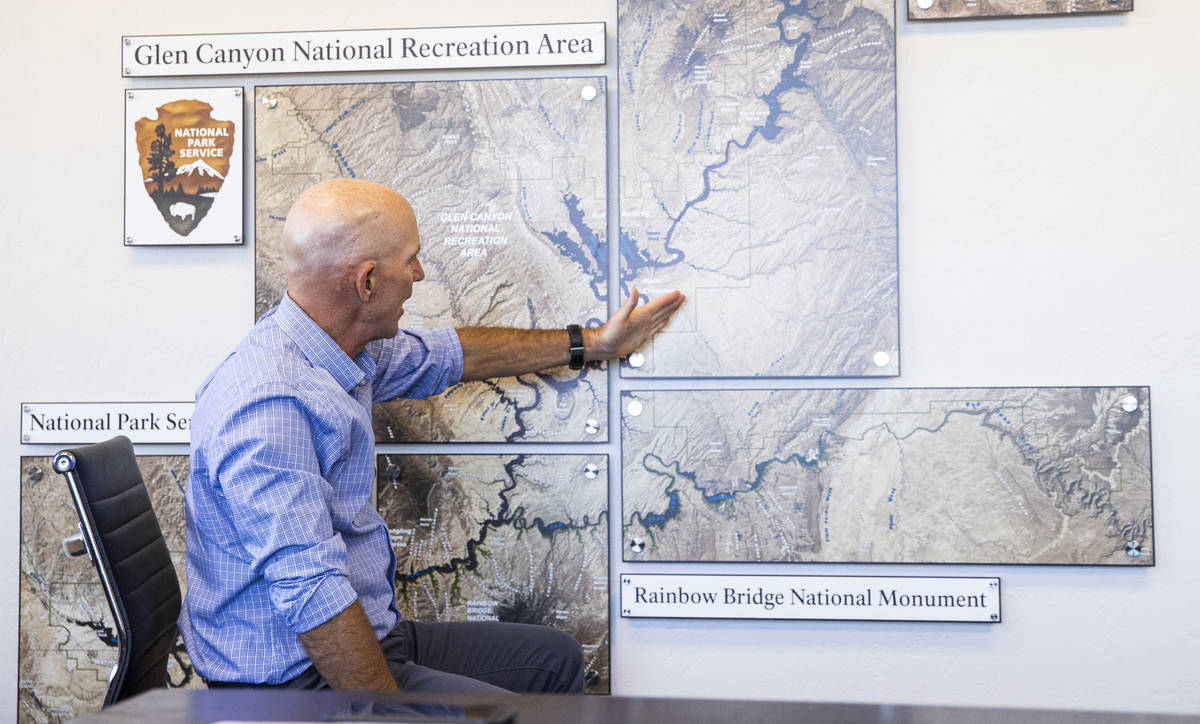

William Shott, superintendent for Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, knows the prospect of losing the main ramp at Wahweap Bay is causing consternation in the community.

All of the concrete at the ramp is now out of the water, so temporary pipe mats are extending the launch area.

Just a few more feet of lake level decline, and the ramp won’t be able to be extended because the area drops off into a canyon, Shott said.

He said once it became clear this year that the water level projections were worsening, the park service identified one goal: maintain minimum access to Lake Powell. That means having one usable ramp uplake in the Bullfrog Bay and Hall’s Crossing area and one downlake in the Wahweap area.

Park officials found an area on Wahweap Bay that could support a ramp, Shott said, so they began investigating further and found records for a ramp that was likely built sometime in the mid-1960s.

Shott suspects it was the first ramp that was built to access the rising Lake Powell.

Now plans are in place to build that ramp out, and Shott hopes it can open by Labor Day. As recently as Tuesday, the park service thought most boaters might not be able to access Wahweap Bay from a launch ramp for weeks.

Page Mayor Bill Diak has expressed frustration that plans to deal with the declining water levels have only recently been developed.

“How long have we been talking about a drought for Lake Powell and Lake Mead?” Diak said Wednesday. “Twenty years? And nobody saw this coming?”

Shott said the park service understands the importance of the lake as an economic driver for the community, and his employees are doing everything possible to maintain access.

Diak said a meeting on Wednesday among businesses, park officials and representatives for elected leaders led to the development of some “Band-Aid solutions” to get his community through a period of limited access to the lake.

On Friday, the park service announced that an asphalt auxiliary ramp will be able to provide limited access while the other is constructed. The asphalt ramp has been submerged under water for years, so use is limited to boats under 36 feet.

Additional releases

Less than a year ago, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation projections indicated that Lake Powell would be in the middle of a normal year, Shott said. But bit by bit, the water level projections began to show a grim picture.

“If you were to tell me Jan. 1 of this year that we’d be having this conversation today, I would be genuinely shocked,” Shott said.

Becki Bryant, a spokeswoman for the bureau’s Upper Colorado Basin region, has said a combination of smaller snowpack, hotter temperatures, less precipitation and dry soils soaking up runoff led to less water flowing into the Colorado River system.

For Lake Powell, that meant 2.5 million acre-feet less water than was expected in the first six months of the year. The reservoir is about a third full, and lake levels are projected to continue declining until runoff season starts next spring.

The falling water level led federal officials to announce in mid-July that the government would take the unprecedented step of releasing additional water from upstream reservoirs to prop Lake Powell up.

Those upstream releases from Flaming Gorge Reservoir, Navajo Reservoir and Blue Mesa Reservoir will boost Lake Powell’s water level by about 3 feet.

The goal is to maintain a buffer from the minimum lake elevation that allows electricity generation at the Glen Canyon Dam, a major power source for the West.

Losing power generation at the dam means losing the flexibility to support demand on the grid, according to Bob Martin, the Glen Canyon field division manager for the Bureau of Reclamation.

At full elevation, the dam is capable of producing 165 megawatts of electricity, but it is down to 111 megawatts, Martin said. Less power generation at the dam means less income to support upkeep and repairs, he said. It also means less money to support environmental programs.

“It’s a big ripple effect for sure,” he said.

Operational changes

Even with the additional water being released into Lake Powell this year, federal projections show the reservoir’s water level hitting a low of 3,516 feet in April. Those levels will start going up when spring runoff begins.

Water level projections that will be released on Aug. 16 are expected to trigger changes along the Colorado River.

In the Upper Basin, Lake Powell is expected to scale back its releases to the Lower Basin by 750,000 acre-feet. One acre-foot of water is about what two Las Vegas Valley homes use over 16 months.

And in the Lower Basin, users also are expected to have their allocations of river water cut under a shortage declaration. Nevada will have its allocation of 300,000 acre-feet cut by 21,000 under two river agreements.

Collectively, the Lower Basin will scale back its allocation of river water by 613,000 acre-feet, according to the Bureau of Reclamation.

While unfavorable drought conditions have strained the Colorado River, Martin said the focus needs to shift to how much water is being used.

The original agreement that established Colorado River allocations overestimated how much water the river would be able to provide, he said.

Over-allocation downstream is apparent, he said, because Glen Canyon Dam continues to release the mandated amount of water, but Lake Mead’s water level continues to decline.

But it shouldn’t fall on one state or group to change course, Martin said.

“We all need to pull together to fix this,” he said.

Contact Blake Apgar at bapgar@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5298. Follow @blakeapgar on Twitter.