Loved ones recall vet’s struggle with PTSD

In his mind, Stanley Gibson rode down the Highway of Death time and time again until that chilly December night when he came to a dead end.

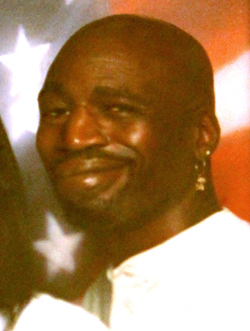

Gibson, a 43-year-old disabled Gulf War veteran suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, was shot dead by Las Vegas police in the early morning of Dec. 12. He was shot in the back of his head "with the same damn gun," Rudy Gibson said, describing the AR-15, the civilian version of the military's M-16 assault rifle.

That was the same weapon that Stanley took with him 20 years ago when they were both deployed in Saudi Arabia for Operation Desert Storm.

Rudy came home with experience as a combat engineer who fixed radios in tanks and tested global positioning gear.

Stanley came home with memories that gave him a serious case of post-traumatic stress disorder as well as cancer he blamed on exposure to depleted uranium shells used in combat.

He was let down by the "system," according to his wife, Rondha, and brother, Rudy, who told the Review-Journal on Friday about the battle he was fighting.

In the end, his death has made a case that steps need to be taken to prevent other veterans like him from falling through the cracks of the VA's health care system and the Police Department that was supposed to protect him.

•••

As a cook, Stanley was not on the front lines of the assault to stop the armed retreat of Iraqi army convoys fleeing from Kuwait City to Basra, Iraq, in February 1991.

Instead, his bout with anxiety from PTSD began in the aftermath of combat when he and other soldiers of the 327th Infantry Regiment were sent in five days later to clean up hundreds of scorched corpses and carbonized bodies that littered Iraq's Highway 80, his wife said. That's where U.S. warplanes had bombed fleeing convoys of tanks and trucks.

"They'd pick them up, put them in body bags, throw them on a truck, take them to an undisclosed location, bury them in the dirt (and) burn that dirt," Rondha Gibson said, describing Stanley's role on the cleanup crew.

"And as you know, once a body is hot like that, you start breathing in fumes. They didn't give him personal protection equipment or none of that. They said, 'Go in and clean it up, and you guys will be OK.' "

Years later, flashbacks would spring to life.

"He'd start screaming and say, 'Why did I do that? What did those people do to us? They didn't deserve it,' " she said, "He'd talk about seeing the bodies. He'd say, 'You know what it's like seeing a dead child and a dead woman melted together?'

"Come on now. No man should have to go through that, and if you do, give them the help they need for that. Don't let them just come back and being a vegetable walking around seeing that in their head over and over again."

The flashbacks from the sights, the smells and toxins from burning oil and perhaps cancer-causing depleted uranium fragments from U.S. anti-tank rounds persisted.

"The system let Stan down," she said. "Within the last year, it really, really started getting bad."

He got to the point he couldn't handle the anxiety any longer, especially after the medication prescribed by doctors at the Department of Veterans Affairs had run out and his appointment to get a new evaluation and another prescription was canceled by the VA.

He sometimes flew into fits of rage and twice slashed his wrists in suicide attempts.

"He thought everybody is trying to kill him. Everybody's conspiring against him," she said, fighting back tears.

"Everybody asked me, 'Well why did you stay and put up with that bullshit.' Well why do you think I did it? I did it because I love that man."

•••

In late October, Stanley and Rondha Gibson came to the Review-Journal and talked about his experience along the Highway of Death and the problems he was having with the VA.

He described the five surgeries for adenoid cancer that left his jaw disfigured and damaged nerves in his face. And he told how the VA's regional office in Reno had reduced his cancer rating, significantly cutting his disability compensation. In addition, officials there concluded he was fit for employment.

But doctors in the VA's Southern Nevada Healthcare System argued he was not.

"It is necessary for him to have a constant guardian for his safety," Dr. Robert Sarazen, of the VA's clinic in North Las Vegas, wrote on Aug. 9.

Over the course of surgeries on his face and roller-coaster ride from having his disability rating reduced, then reinstated, then reduced again, Stanley lost trust in the VA.

"A veteran comes in and says, 'I know what's wrong with me, can you help me?' And you get these people who just don't care," Rondha Gibson said. "When one of the veterans calls and says, 'Hey, can you help me out?' don't be rude. Don't say, 'Hold on a minute,' like it's bothering you."

Rudy Gibson, who works as a state veterans representative for Nevada Job Connect, said he "was doing everything I could to try and find him help," but getting him to trust the VA after all his denials was the toughest hurdle to overcome because of the mindset he observed.

"They've got better things to do. It feels that way," he said.

•••

The VA's regional office in Reno didn't return calls seeking comment on Stanley Gibson's case, but a spokesman at the VA's office in Los Angeles said the agency is not able to comment because of privacy laws.

Although he couldn't comment on Gibson's case, Dr. Ramu Komanduri, chief of staff for the VA Southern Nevada Healthcare System, offered some general insights on the system's growing program for dealing with PTSD.

The number of Southern Nevada veterans with mental health problems has doubled, from 5,000 to 10,000, in the past six years. And the number of vets diagnosed as primary PTSD cases has risen from 724 in 2005 to 3,600 -- nearly a fivefold increase.

During the same time, the VA's mental health staff of psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, nurses and case managers has nearly doubled from 60 to "well over 100," Komanduri said.

The VA Southern Nevada Healthcare system is trying a variety of techniques from one-on-one counseling for the most severe cases to group counseling and cognitive processing to help vets with PTSD to gain a sense of control over their lives.

"We're hiring additional personnel," he said. "It's likely that we are going to see a significant rise with veterans as they move to our community, reporting more of their PTSD experiences.

"The biggest challenge for us is to convince the veterans they need to come in."

The Southern Nevada system has no control over how benefits are decided. That is left up to VA officials at the regional office.

"My goal is to make the health care the best possible," Komanduri said.

Like exposure to Agent Orange that affected Vietnam War veterans, the VA is still grappling to find a link between what is known as Gulf War syndrome and suspected mental and physical illnesses.

"There has been discussion of Gulf War syndrome from oil wells and oil fires. There was also talk about vaccinations and talk about (depleted uranium) exposure. All of that has been discussed, but there hasn't been definitive proof," he said. "Agent Orange and diabetes wasn't conclusively linked until years later after the Vietnam War. It took years to prove a definitive link."

•••

Over past several months, a series of events and miscues built to the tragedy that left Stanley Gibson dead.

Already distraught over having his disability rating reduced, someone poisoned his dog, Shalifi, a loyal companion who had helped him cope with stress, on Oct. 12.

Two weeks later, when he tried to find out why his cancer rating had been reduced, he became loud and boisterous and was apprehended by security officers for aggressively confronting a doctor at the VA's Southwest Clinic. He later pleaded guilty in U.S. District Court to one count of assaulting a federal employee.

On Nov. 12, he called the Review-Journal saying he was a "desperate man," because the couple's rental home went into foreclosure and they were being evicted. They moved a few weeks later to a northwest apartment complex, not far from where he was shot.

His medications were running out on Dec. 7, when staff at VA Southern Nevada Healthcare canceled the appointment to renew his prescription. The doctor's husband had been hospitalized, so clerks canceled all her appointments for the day though she showed up for work, his brother said.

Komanduri said he couldn't comment on the canceled appointment. But he noted that the VA system has a back-up plan to deal with such incidents, and there is no reason for anyone to run out of medication.

"We have a walk-in appointment for any day when a veteran can walk in and see a mental health provider," he said. "That is available for any veteran any day. If they need refills of medication, that's there. We can give you same-day mental evaluation."

Stanley's mental outlook took a turn for the worse.

Two days before he died, he was taken to the Las Vegas jail after he was stopped by police during a mental breakdown. He was supposed to be put on a 72-hour psychiatric hold but was released less than eight hours later.

The next night, he got lost on his way home and turned into the wrong apartment complex. Mistaken for a burglar, police responded and wedged his car between two cruisers. After a half-hour, they tried to flush Gibson, who was unarmed, from his car by firing a nonlethal beanbag shotgun blast. They planned to use pepper spray to get him to leave the car.

Hearing the blast, Las Vegas police officer Jesus Arevalo fired seven rounds into the car, killing Gibson.

In the aftermath, police said it wasn't clear why Arevalo discharged his semiautomatic rifle. But sources said a breakdown in communication might have contributed to the shooting.

•••

Stanley LaVon Gibson will be buried Friday with full military honors at the Southern Nevada Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Boulder City.

Rondha Gibson said she will never forget his after-surgery smile and how his disfigured face bothered him.

"He was always saying, 'Boog, why are you with me? Why are you being with the ugly person?' " Rondha said.

"And I'd say, 'Because I don't see nobody ugly in front of me. I see a beautiful man in front of me.' That smile he had, to me, could raise the sun for me and put the moon to bed for me as far as I'm concerned."

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@review journal.com or 702-383-0308.

Related column

Stanley LaVon Gibson a name to remember

Deadly Force

When Las Vegas Police Shoot, and Kill