Dwindling band of Pearl Harbor survivors hope attack’s lessons outlive them

As they prepare to mark the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor on Wednesday, Las Vegas veterans who lived through it say they fear the lessons of the surprise raid by Japanese warplanes and the global war it helped set in motion are being forgotten as their numbers dwindle.

“After World War II and all that the country and ourselves have been through, I thought we had accomplished a peaceful world, and peace for our nation,” said Lenoard Nielsen, 94. “Today, 75 years later, I question any part of that being the truth.”

Ed Hall, one of the last presidents of the disbanded local chapter of the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association, said members used to give talks at Clark County schools “to keep the children updated on history.” That ended a few years ago when he never received a response from the Board of Education to the annual offer.

“I think it’s a darn shame,” he said. “I was very hurt by that.”

While roughly 20,000 U.S. military personnel made it through the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Nielsen and Hall, 93, are among the last few survivors living in the Las Vegas Valley and members of a shrinking band estimated at several hundred nationally.

Because they are too frail to travel, they won’t be among the 200 survivors gathering at the 75th commemoration events in Hawaii.

But as they’ve done every year since the attack, they will remember friends they lost and the tragedy they experienced on that “date which will live in infamy,” as President Franklin D. Roosevelt described it the next day when he asked Congress to declare war on the Empire of Japan.

‘IT BOTHERS ME GREATLY’

They also will undoubtedly reflect on the irony of the world slowly forgetting such an important milestone in U.S. history and an event forever seared into the memories of those who witnessed it.

“It bothers me greatly,” Nielsen said, referring to “the turmoil and the problems that we have within our own country let alone the world. … I’m not sure we have gained an awful lot from that experience.”

Nielsen, then a 19-year-old sailor, recalls watching in disbelief from the deck of a hospital ship as swarms of Japanese warplanes swooped down on Pearl Harbor and unleashed bombs and torpedoes. He saw the final bomb hit his former ship, the USS Arizona, engulfing it in flames before it sank.

“We couldn’t come to realize what was really happening. It was such a terrible thing before our eyes,” he said recently at his Las Vegas apartment.

Hall, an 18-year-old Army Air Corps soldier at the time, stood outside a mess hall at nearby Hickam Field while a Zero flew at him, its machine guns kicking up chunks of asphalt.

“I’m staring at him in awe, not believing what I’m seeing,” he recalled. “He couldn’t have been more than 25 to 30 feet off the ground. He had to pull up to miss the building and telephone wires.”

Richard Hackett, another local veteran, was lined up in formation that Sunday morning outside the Naval Station barracks when a Japanese plane flew so low over Honolulu the 20-year-old sailor could see the pilot’s face.

“I thought he was lost,” he said. “We didn’t know what was going on until one of the officers told us Pearl was under attack.”

DIVING INTO WAR

From their respective perches, the men were witnessing the first wave of “Zero” fighters, “Kate” torpedo planes and “Val” dive bombers launched in a 90-minute span from six Imperial Japanese Navy aircraft carriers beginning at 6:05 a.m.

There were 183 in the first wave and 167 in the second, according to Las Vegas military historian Bill McWilliams, a former fighter pilot and author of “Sunday in Hell,” a minute-by-minute account of the attack.

The first target hit was Kaneohe Bay Naval Air Station at 7:48 a.m. based on the account of a sailor in the barracks who had glanced at his watch when he heard gunfire. Eleven Zeros strafed the tarmac and hangars where 30 Navy PBY-5 aircraft were parked. Japanese bombers followed to essentially destroy the Navy’s long-range patrol capability.

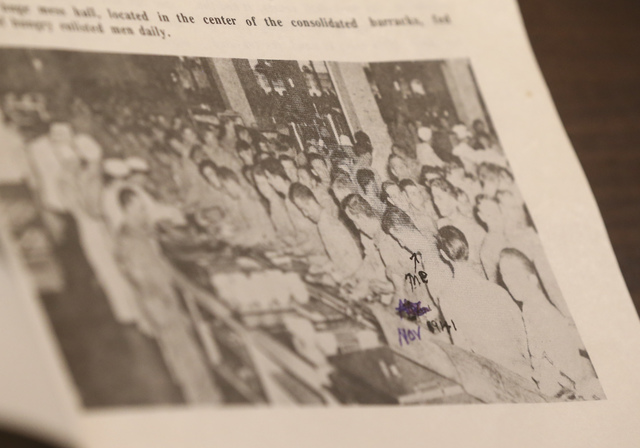

Seven minutes later, at 7:55 a.m., the assault on Pearl Harbor and Hickam Field began. Historians estimate 50 Japanese dive bombers and fighter planes struck the airfield, killing and wounding many in its 3,200-man barracks.

The greatest number of casualties occurred on Battleship Row, where most of the Pacific Fleet was moored. Of the 2,403 men and women who died in the attack, almost half — 1,177 — were on the USS Arizona. Among the 335 on board who survived was Clarendon Hetrick, who lived to 92 before dying in Las Vegas in April and was among the last seven USS Arizona survivors.

He had just finished busing dishes after breakfast on the ship and had taken a shower when he heard explosions.

He ran to his battle station, the third-deck ammunition magazine, where he started handing up shells for topside guns. “We took a hit. It knocked us all off our feet. We started smelling smoke, and somebody said, ‘Get the hell out of here!’” he said in his last interview with the Review-Journal a year ago.

He survived by plunging into the briny water as the ship sank. Then he dog-paddled to Ford Island, even though he had flunked the Navy’s swim test.

RESCUE AND RECOVERY

Nielsen, an apprentice seaman from Salina, Utah, was aboard the USS Solace hospital ship recovering from an emergency appendectomy. He had been assigned to the USS Arizona out of boot camp, but was granted a transfer to serve with a childhood friend aboard a heavy cruiser, the USS Pensacola.

That ship left Pearl Harbor on Nov. 29, 1941, to take Marines to Midway Island, but Nielsen was too sick to make the trip.

Instead, eight days later, he joined other volunteers to rescue fellow sailors from the fiery oil slick created by the air attack. They hopped in longboats and gigs and rushed toward the black smoke billowing from the Arizona.

“We had a hard time making our way through the oil,” he said, shaking with emotion as he described hauling “badly burned people and badly injured” into the boats. “I don’t know for sure how many trips we made but at least a half-dozen.”

Ray Turpin — a young Marine from Waterloo, Alabama, who had lived in Las Vegas for decades before dying in 2009 at age 88 — saved five men with the help of a chaplain, pulling them through a porthole on the capsized USS Oklahoma as the ship filled with water.

He recalled in 2008 how he tried to save the chaplain, Father Aloysius Schmitt, of St. Lucas, Iowa, as well.

“I was looking in his eyes and he said, ‘I’ve already tried. I can’t get out.’ He walked away and he said, ‘I’m going to look around and see if there are any more guys that I can help get out of here.’ So I waited a few minutes. He never came back. I never saw him again,” Turpin said of Schmitt — one of 429 from the Oklahoma who died in the attack.

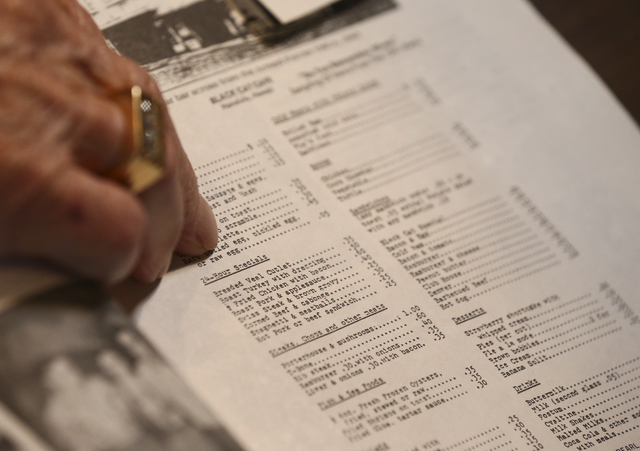

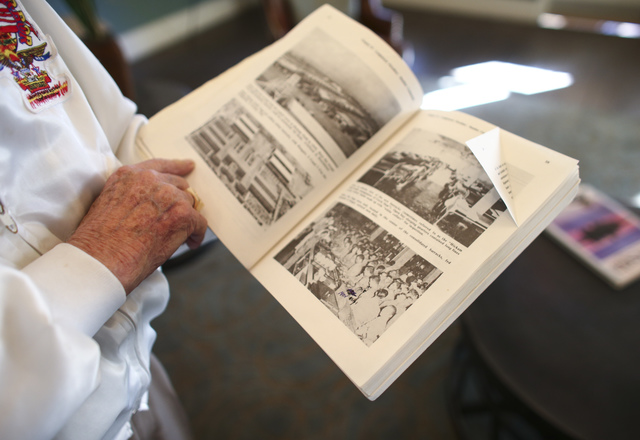

At Hickam Field, the duties of Hall — an Army private from Greenwood, South Carolina — quickly changed from scrubbing a frying pan to driving a makeshift ambulance.

From the mess hall he “heard the loudest explosion.”

“I thought, ‘What in the world is going on?’” he said. “I went to the back door, looked up the street and Hangars 7 and 9 were blowing up” and “all these guys running out” of Hangars 2 and 4.

Seconds later, Hall saw “puffs of asphalt kicking up” as a warplane barreled toward him strafing the ground before pulling up.

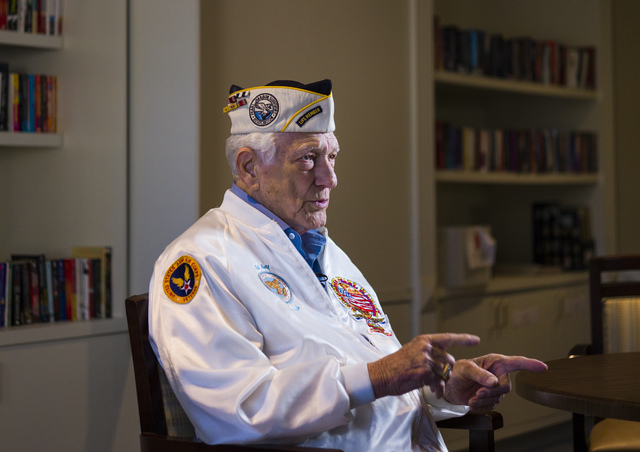

“I’m looking up, and he’s looking down, the damn pilot. That’s when I saw the red balls, and I said, ‘Holy mackerel. It’s the Japs,’” Hall said recently, sitting inside the library at the senior living complex in northwest Las Vegas where he lives.

Minutes later he hustled to the motor pool and drove off in a pickup. He was flagged down by a medic and they spent “quite a few hours” taking wounded soldiers to medical facilities and recovering the dead.

Hall said he still gets “choked up thinking about how we picked up those terribly wounded people, arms missing, stomachs ripped open, faces shattered. … It was a terrible day.”

Hackett, an electrician’s mate from Madison, Wisconsin, was on shore patrol in Honolulu during the attack. His job “got to be practically a blur,” the 95-year-old Navy veteran said, sitting in an easy chair at his Henderson home.

While he later enforced martial law, his first assignment was “running around whorehouses” to roust servicemen back to ships and duty stations.

“I was sent in there to make sure they were gone,” he said. “If there’d been any in there I’d run them out.”

Later Hackett was sent to the USS Utah to recover live rounds for reuse. “It was laying on its side,” he said. “We went down in there in water up to our necks and groped around and got 3-inch ammunition.”

‘THEY MISSED’

Jack Leaming, a Las Vegas Pearl Harbor survivor who died in 2013, was one day past his 22nd birthday when he and Navy pilot Dale Hilton took off in a Douglas scout/dive-bomber from the deck of the USS Enterprise at 6 a.m., shortly before the sneak attack. He was manning the plane’s machine gun and the radio while scouting for Japanese boats south of Pearl Harbor.

As they flew ahead of the Enterprise with an open canopy, he said he and Hilton could smell smoke from the USS Arizona even before Oahu came into sight.

As they drew nearer, Japanese planes opened fire on them.

“They missed,” Leaming, of Wildwood, New Jersey, told the Review-Journal in 2010. “Hilton put that thing in a diving turn. We leveled off barely over the top of the sugar cane.” Of 18 scout planes dispatched from the Enterprise, Leaming’s was one of nine that landed safely.

Three months later, their plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire and forced to land on the water near Marcus Island. He was captured shortly after it sank.

He not only survived the Pearl Harbor attack but also more than 3½ years in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps. He was liberated at Osaka, Japan, on Sept. 6, 1945, four days after representatives of the Japanese empire formally surrendered on the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2.

RELATED

Remembering the USS Nevada's daring run for the sea during attack on Pearl Harbor