Pro-plaintiff judge picked apart by high court

You can’t prove that a rear-end collision didn’t cause injuries when the trial judge refuses to allow evidence that might show an accident was too minor to cause such harm.

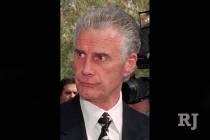

Clark County District Judge Jessie Walsh issued such a pro-plaintiff ruling, not once, but again and again in a case brought by the Eglet Wall law firm.

In one extraordinary action, Walsh became so angry at a defendant’s attorney, Stephen Rogers, she ended a two-week jury trial. She sanctioned Rogers for misconduct, threw out his defense, dismissed the jury and ordered a $5 million judgment against his client, Jenny Rish.

In March, the Nevada Supreme Court ruled Walsh had made so many errors in a 2011 trial that a new trial was warranted.

A 19-page opinion authored by Justice James Hardesty and signed by Justices Michael Douglas and Michael Cherry detailed Walsh’s errors and said she abused her discretion when determining whether to admit or exclude evidence.

By pointing out all her errors in a factual manner and explaining why she was so wrong so many times, the justices essentially filleted Walsh for her poor judgment.

Records from Westlaw show that since January 2000, out of 35 Walsh cases that have been appealed, she has been reversed in 13 of 25 published cases and 4 out of 10 unpublished cases. Simao v. Rish is just the latest to be overturned.

What is not disputed: On April 15, 2005, Jenny Rish was driving on Interstate 15 near the Cheyenne Avenue interchange behind a van driven by William Simao, 41, who owned a floor and tile cleaning business. In stop-and-go traffic, his van moved forward a few feet. Rish, then 60 years old, hit her brakes, but not hard enough, and rear-ended his van.

Simao testified the back of his head hit the steel cage behind his seat. An ambulance was called, but Simao refused treatment. Later that day, Simao complained of head, neck and shoulder injuries and went to an urgent care facility. Over the years, he claimed nearly $200,000 in medical expenses.

Neither Rish, a retired bank teller from Arizona, nor her passengers were injured.

What is disputed: Did a seemingly minor rear-ender cause Simao’s subsequent medical woes and require numerous treatments?

Two years later, Simao and his wife, Cheryl Ann, filed a personal injury lawsuit against Rish.

During pretrial hearings, the Simaos’ attorneys, former District Judge David Wall and Robert Eglet, sought to limit testimony that might convince a jury it wasn’t possible for a low-impact accident to cause Simao’s subsequent injuries. Walsh agreed to limit such testimony and evidence, relying on a previous court ruling that didn’t say what she thought it did.

Among Walsh’s legal errors identified by the Supreme Court:

— She misunderstood a prior case, Hallmark v. Eldridge, and erroneously decided Rish’s attorney should have hired a biomechanical engineer to prove the accident didn’t cause Simao’s injuries. The justices decided she abused her discretion by blocking Rish from presenting evidence and testimony from a doctor or witnesses regarding the nature of the accident.

— She erred in striking Rogers’ answer, entering her own judgment and conducting a hearing setting the $5 million judgment, which included more than $1 million for attorney fees for Eglet Wall. “The district court imposed a case-ending sanction by striking Rish’s answer, entering a default ad conducting a prove-up hearing,” Hardesty wrote.

— Her pretrial order prohibiting the low-impact defense lacked specificity. Rogers repeatedly asked for clarification, and she refused to clarify it. She “appears to broadly construe the term low-impact defense to include the facts before, during and after the accident,” Hardesty wrote.

— There was no clear violation of her order, let alone misconduct by Rogers, because Walsh “never described how the alleged instances of misconduct violated the pretrial orders,” the justice wrote. She had claimed eight violations by Rogers.

— There was no misconduct by Rogers to cause Walsh to sanction him by striking his defense. “We note that the district court never described how the alleged instances of misconduct violated the pretrial orders,” Hardesty wrote.

The $5 million judgment Walsh ordered included $194,390 for past medical expenses, $2,518,761 for past and future pain and suffering and loss of enjoyment of life, and attorney fees of more than $1 million. Cheryl Simao was awarded $681,286 for loss of consortium. The justices vacated that order, stating that $1 million in legal fees won’t be going to Eglet Wall.

Despite all this, the Supreme Court justices didn’t find bias on Walsh’s part, so she will try the case a second time. The trial is now set for March 2017, about 12 years after the accident.

The case has evolved into a battle of the legal titans of Las Vegas with Eglet and Wall on one side and Rogers on the other. But Rogers pulled in some big guns to help with the appeal — attorneys Dan Polsenberg and Joel Henriod.

In the next trial, Walsh, long one of the lowest-rated judges in Review-Journal judicial performance surveys, won’t be able to keep so much information from the jury. The Supreme Court put a stop to that.

Jane Ann Morrison’s column runs Thursdays. Leave messages for her at 702-383-0275 or email jmorrison@reviewjournal.com. Find her on Twitter: @janeannmorrison.