Mom advocates seat belt law

Kelly Thomas-Boyers watched a single tear roll down her son's cheek.

The tear came eight days after the crash.

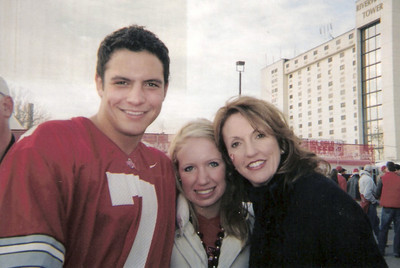

Adam Thomas was heading to see a movie premiere of "300" on a Friday night in March 2007. The 21-year-old had spent the day working as an intern for the Legislature in Northern Nevada.

Adam and a friend were in a Ford Expedition and had just driven onto Interstate 80 on their way to the theater. It's estimated the vehicle was only going about 50 mph.

There was something -- or someone -- in the middle of the freeway and the Expedition swerved. It flipped and rolled over.

The roof caved in and Adam was ejected. He was taken to a Reno hospital in critical condition.

His friend walked away from the crash.

Adam wasn't wearing a seat belt.

His friend was.

It's been two years since Adam's crash, but Kelly still weeps as she recalls the first time she saw the CAT scan of his brain.

Her 21-year-old son had looked his regular self in the hospital bed.

The CAT scan showed the bleeding. Adam had suffered severe head trauma.

To relieve the pressure on his brain, Reno physicians removed part of Adam's skull.

Five days after the crash, doctors told Kelly that Adam "was out of the woods." He would need rehab. Lots of it. They told Kelly to save her strength. This would be a marathon.

Kelly pondered how this could have happened.

In high school in Las Vegas, Adam was the teen all the other parents wanted at the wheel when the kids hung out. He was responsible and safe. He was a defensive driver, Kelly said.

But most of all, Kelly always knew her son to wear a seat belt.

Adam was a senior at the University of Nevada, Reno, where he studied journalism and political science. He had gained confidence about his future after landing an internship with state Sen. Mike Schneider, D-Las Vegas.

Maybe Adam suffered from a youthful sense of invincibility.

Maybe he hadn't worn the seat belt because the theater was close by.

If Nevada law was tougher on people who didn't wear seat belts, would he have buckled up?

Since the crash, Kelly has become an advocate for making failure to wear a seat belt a primary offense in Nevada. Not wearing a seat belt is currently a secondary offense, meaning motorists can only be cited if they are pulled over for another offense.

This past week, state legislators, including Schneider, introduced state Senate Bill 116 hoping to change the law. The same bill died in the 2007 session.

The bill would give law enforcement the authority to pull someone over for not wearing a seat belt. The offense carries a $25 fine.

Opponents of the primary seat belt law point to studies that indicate over the past several years more than 90 percent of Nevada's drivers wear a seat belt.

The problem with those surveys, annually conducted by the Nevada Department of Public Safety, is that they observe drivers between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. The fatality statistics show a much different number.

In 2007, 254 people were killed in passenger car and light truck crashes in Nevada. In those crashes, 124 people, nearly 49 percent, were not wearing a seat belt.

According to state traffic safety advocates, 199 people were killed on Nevada roads in 2008. Though total fatalities went down, the percentage of those who died without being belted in went up. Fifty-four percent were not restrained, according to the Nevada Seat Belt Coalition, a group advocating the primary seat belt law.

Still, if so many motorists are wearing seat belts, how could changing the law make a difference?

There is every indication that motorists respond to the fear of getting a ticket.

Take a look around and think about it the next time you see a motorcyclist not wearing a helmet. The state demands that motorcyclists wear helmets or they will face fines. As a result, most do.

Nevada's death rate for people who aren't buckled in during crashes is higher than that in 15 of 26 states that have primary seat belt laws.

According to a study by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the percentage of unrestrained people who died on roadways in California and Oregon in 2007 was 33 percent. In Washington, it was 37 percent.

Traffic safety advocates such as Kelly believe these lower percentages are due in large part to the primary seat belt laws in these states.

But preventing people from dying isn't the only reason to pass the bill, advocates say. There are millions of dollars at stake.

The Nevada Seat Belt Coalition estimates the state could save $2.7 million for fatalities prevented, $50 million in critical injuries prevented and $33 million for non-life threatening injuries prevented.

These extravagant dollar amounts are the costs associated with each serious or fatal crash. Normally these crashes call for a response by up to 30 emergency workers, including firefighters, police and medical personnel, as well as city or county employees. Then there's the costs for the hospital staffs, the morticians, and cleanup crews. And finally, all those drivers stuck in traffic means a loss of productivity.

Clark County could save more than $2 million in the first year of the law, according to a research project by the Preusser Research Group, a firm specializing in transportation and highway safety issues.

And in these tough economic times, the state could receive millions of dollars in funding through the federal Transportation Equity Act by making wearing a seat belt a primary offense. That's the old carrot leading the horse.

Kelly, along with other advocates -- including doctors from University Medical Center, traffic safety advocates, and law enforcement from throughout the state -- will present this case to state legislators as the bill moves to the state Transportation Committee in the coming weeks.

Kelly believes if Nevada had a primary seat belt law two years ago, it would have made the difference to her son.

"If not wearing a seat belt was his habit, a law would have made a difference," Kelly said. "If he had been ticketed one time, it would have changed his mind."

Eight days after the crash, Adam's condition had grown dire. The pressure from the bleeding in his head was affecting his brain stem, which controlled his breathing.

These days, Kelly fights through tears and her voice cracks recalling that day.

"I never was sure how much he was aware of what was going on," she said. "That afternoon he shed one tear. I knew that he knew. That was the only way I could tell he understood what was happening."

Adam died later that evening.

Kelly has cried many tears.

But she fights on, for a law she believes would have saved her son's life. She does it for him and so others won't suffer as she does.

"In the end, I'm still without a son, someone who was my best friend. That's something I will deal with forever. But I know he would have taken up this fight, too. I take this forward in his memory."

• • •

Next Sunday's Road Warrior column will focus on those who have concerns about changing Nevada's seat belt law.

If you have a question, tip or tirade, call the Road Warrior at 702-387-2904, or e-mail him at roadwarrior@reviewjournal.com. Please include your phone number.

Eastbound Twain Avenue will be closed under Interstate 15beginning at 8 tonight through May, the Nevada Department of Transportation announced. The closure is part of the ongoing I-15 express lane project, which will see the interstate widened from eight to 10 lanes from Sahara Avenue to Interstate 215. Motorists should watch for posted detours.

The California Department of Transportation announced that blasting on Interstate 15 at Mountain Pass, south of the Nevada border, will wrap up Wednesday. Officials originally believed that 15 days of blasting, scheduled for every Wednesday through April, would be needed for the interstate widening project. Apparently eight is enough.

The last blasting session will take place from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Wednesday. Northbound I-15 drivers will experience delays of about 15 minutes. During the closure, I-15 southbound traffic will be diverted to the Primm Valley properties for fuel, food and other services. Truckers are encouraged to exit I-15 at Jean. Motorists are advised to plan ahead and avoid traveling south on I-15 during those hours. Visit www.caltrans8.info or call (866) 383-4631 to learn more about this project.

New traffic signals have begun operating at the intersection of Grand Central Parkway and Clark Avenue. Motorists should use caution in the area until becoming familiar with the new signal. The traffic signals are needed for the ACE Downtown Connector and ACE rapid transit system.

Las Vegas Review-Journal