Pat McCarran

For 20 years, Pat McCarran ran Nevada through his political machine.

It replaced the machine of George Wingfield, which existed mostly to enrich Wingfield and his cronies. McCarran believed his served the interests of all Nevadans.

He helped bring heavy industry to Southern Nevada and keep it here. He was one of those responsible for Nellis Air Force Base and civil aviation. He helped keep Nevada silver in every American's pocket money until after his death in 1954. He helped keep Franklin Roosevelt from packing the U.S. Supreme Court with New Deal Democrats. McCarran was a second-generation Irish-American. During the Potato Famine of the 1840s, "his father came over at the age of 14, his family having starved, and his mother came over in steerage," wrote McCarran's daughter, the nun Sister Margaret P. McCarran.

Nevada's first McCarran became a sheep rancher. Patrick McCarran, born in 1876, grew up on his father's ranch on the Truckee River about 15 miles east of Reno.

He had no childhood playmates, and as an adult never developed a social life. Even though the ranch's isolation afforded few opportunities to formally practice his Catholic religion, it remained important to him. The few mandatory Masses gave him an opportunity to converse and roughhouse with others his age. He remembered those occasions with special fondness in a letter to his daughter:

"We would together kneel and examine the conscience and read the prayers before Confession, then to the dear little Confessional where the freckled faced boy told all the terrible sins which a freckled faced boy with only a dog for a playmate might be guilty of committing."

He didn't start grade school until he was 10, and never caught up to others his age. But being more mature than classmates had its payoffs; graduating from Reno High School at nearly 21 years of age, he was valedictorian and had broken school records for both the 50- and the 100-yard dash. At the University of Nevada he excelled in debate, wrote for the school newspaper, and had tolerable grades. However, he dropped out when his father's ill health required him to take over the family ranch.

McCarran was as respected as it is possible to be in Nevada while remaining a sheepherder.

In 1902, Silver Democrats recruited him to run for the Nevada Legislature. Though silver was primarily a national issue, the silver crowd needed to control the upcoming Legislature because it would select a new U.S. senator to represent Nevada. McCarran's platform also included eight-hour day, pro-labor and anti-trust planks. He won.

McCarran soon was recognized as an able and particularly hard-working legislator, largely because he cleverly got himself appointed correspondent for a Reno newspaper, and wasn't shy about mentioning himself in his stories.

McCarran married in 1903. He ran for the Nevada Senate in 1904 and lost decisively. He educated himself in law by private reading and passed the bar exam in 1905. He moved to Tonopah the same year.

Tonopah had sprung up in 1900 around an important silver strike, and another strike in 1902 spawned nearby Goldfield.

One of McCarran's biographers, Jerome Edwards, thinks McCarran realized "the political center of Nevada had gravitated to the mining-boom towns. Tonopah was new; there was no established element jealously guarding its political and financial prerogatives. Everyone was in on the ground floor; everyone was a carpetbagger." Central Nevada was thus a good stage on which to play out his plans, which at the time included both becoming famous politically and getting rich.

He did neither in Tonopah. He proved himself a brilliant defense lawyer, good enough to get elected district attorney. But he was not as successful at prosecution. "His heart was with the sinner," explains Edwards.

It was during his Tonopah years he ran afoul of George Wingfield, who sometimes was called "owner and operator of Nevada." McCarran represented Wingfield's wife in a divorce. Wingfield won annulment instead of divorce.

During labor troubles that began in 1907, McCarran alienated Wingfield and his mine-owner allies by criticizing the Nevada governor for calling in troops and, later, forming a Nevada State Police Force.

"The plan of Governor Sparks to equip a body of Texas Rangers and vest these horsemen with power to use their shooting irons at will in the settlement of labor controversies would be more than a state disgrace," he said. Such statements may have been directed at the state's usurpation of local authority more than against management, but Edwards says they got McCarran a reputation as a dangerous radical. When he ran for Congress in 1908, Democratic Party bosses shunned him like a leper.

In 1912 McCarran was elected to the Nevada Supreme Court, an office usually considered the crowning achievement of judicial careers but the terminal act of political ones.

McCarran, however, tried to beat the system in 1916 by running for a seat in the U.S. Senate. He thus completed his alienation of Sen. Key Pittman, who wasn't through with the seat, and their feud eventually split the Democratic Party. Pittman won the nomination handily. In retaliation, Democrats refused to work for McCarran two years later when he sought re-election to the Supreme Court. Court incumbents almost never lose, but McCarran managed to do so.

McCarran was a good justice whose decisions are still admired and cited 80 years later.

His political career, however, did not seem so brilliant. For 14 years he was a perennial loser.

In 1932 McCarran challenged U.S. Sen. Tasker Oddie. The Republican Oddie was popular and had lots of money. McCarran ran on a shoestring, but the Democratic Party allowed him to coast into the race without a primary opponent, because nobody else would risk getting slaughtered by Oddie in the general.

Most folks thought it would take a miracle to beat Oddie, but a bank failure sufficed. The chain of banks run by Wingfield failed a few days before the election. Most of Nevada's state funds were in these banks. Oddie, who was closely associated with Wingfield, got some of the blame.

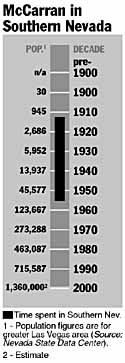

Two other factors helped McCarran. Franklin Roosevelt won the presidential election by a landslide, and the same voters who turned out for him supported other Democrats. Also, Clark County's population had boomed with the construction of Hoover Dam. Nearly all newcomers were working folk, disproportionately from the South, and Democrats for both reasons.

McCarran went into the Senate by 21,398 votes to 19,706. He was already 56, yet would serve more than 20 years.

McCarran, who had learned a great deal about political machines in 30 years of being trampled by one, promptly began building his own. McCarran's machine eventually replaced Wingfield's and enlisted some of Wingfield's veterans. Even Wingfield eventually became friendly.

Despite recent Democratic backing, he couldn't count on continued support, because the party was led by his sometime enemy, Sen. Pittman. So McCarran devised a machine that would be only secondarily loyal to the Democratic cause but primarily loyal to him.

McCarran wrested control of many federal appointments in Nevada from the senior senator who normally would have made them. He did it by threatening to oppose Pittman's important appointments on the Senate floor, unless he was allowed to appoint underlings in the same office.

Each McCarran appointee knew part of the deal was working for McCarran in federal elections. This was already illegal, but the Hatch Act was ignored in Nevada. McCarran got Pete Petersen, a Danish-born labor leader who had never worked in the postal service, appointed postmaster of Reno. In turn, Petersen served openly as McCarran's right-hand man.

McCarran also controlled many state appointments and even city appointments. He controlled federal funds and was not above suggesting some person -- a future political ally -- needed a particular job.

About 1937 McCarran made an alliance of convenience with gubernatorial candidate E.P. "Ted" Carville. Pittman remained theoretical head of Nevada's Democratic Party, but was falling into complete alcoholism and was more interested in national and international issues. McCarran became the real power, and soon fell out with Carville.

Pittman died in 1940 and Carville, by then governor, appointed Las Vegan Berkeley Bunker to replace him in the Senate. Bunker served out the term, but lost the next Democratic primary to a McCarran-backed man. In 1945, when Bunker's successor died in office, Carville named himself to the Senate. McCarran got Bunker to run against Carville, and Bunker beat him in the Democratic primary, then lost to a Republican dark horse, George "Molly" Malone, in the general.

If McCarran was deeply disturbed about losing a Democratic seat in the U.S. Senate, he never showed it convincingly. Carville, too independent for McCarran's taste, was out of his hair. In 1950, McCarran backed Republican Charles Russell for the governor's seat against Vail Pittman, brother to the late senator and the candidate of McCarran's party. Russell won.

McCarran, however, knew Jesse James' secret: You can kill a few people if you're nice to everyone you don't yet need to kill. Most Nevadans were in the latter category, and therefore loved the nice man in Washington.

Young Harley E. Harmon wanted a job in civilian aviation, and went to McCarran's office to ask for a contact. Harmon described the meeting in an interview, nearly 60 years later, with the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

"He got on the phone and said, 'Get me the chairman of the board of Pan American Airlines.'

"Somebody told him, 'He's in a meeting.'

"He said, 'I don't give a damn where he is, I want to talk to him.' "

Half an hour later, the chairman of the board of Pan American Airlines was on the phone, offering an unknown young Nevadan a meeting with the airline's personnel director himself. All Harmon had to do was get to New York.

"No, no," said McCarran. "You have him come down here and we'll interview him in my office." The personnel director did come to Washington, and Harmon, not surprisingly, was hired.

The senator juggled his Senate staff to require more part-time workers than full-time, so more Nevada kids could work there while attending Washington-area law schools. Some of these men, such as Grant Sawyer, Jon Collins and Harvey Dickerson, became the next generation of leaders for Nevada.

McCarran believed that nearly anything could be accomplished through politics. Joe McDonald Jr., son of a Reno newspaper publisher, was captured when Wake Island fell. McCarran tried to get the young man released by declaring him a working journalist, which was at least arguably true. He contacted the Vatican. Some say he even asked his friend Francisco Franco, the fascist but neutral dictator of Spain, to pull strings in Japan. McCarran never gave up until nuclear weapons ended the war and brought freedom for surviving POWs, including McDonald.

McCarran worried about money and had a bad reputation for not paying even ordinary expenses, such as gasoline bills and mortgages. Yet, while some of his appointees used their offices for personal gain, most believe McCarran never did.

Eva Adams, his office manager and later director of the U.S. Mint, remembered an incident in which McCarran asked her to find somebody a job on Capitol Hill. In an oral history collected by the University of Nevada, Reno, she explained that she found a job, and all was fine until the candidate's father showed up to cement what was already a done deal.

"Normally the door was always open, between my office and the senator's. This man closed the door. All of a sudden that door flew open; the senator had him by the back of the neck and the seat of the pants propelling him out of the office.

"And it was tragic because he was trying to give the senator $2,000 to get his son this job, which the senator had already gotten for him. But oh, he was insulted!"

The senator was involved in bringing war industries to the site that eventually became Henderson, and after the war helped make sure they were converted to private production instead of dismantled.

After the Kefauver Committee hearings in 1951 gave gambling a new black eye, a bill was introduced in Congress to place a 10 percent tax on all gaming transactions. Not the profits, but individual bets. That would have killed casino gaming. McCarran fired his ammo and then threw the pistol, trading votes on important national issues for those that would save casinos, which he did.

McCarran fought obsessively for the remonetization of silver, which endeared him in the Silver State but appeared small-minded to much of the country. Ironically, Adams, his protege, would be director of the U.S. Mint a decade after his death, when the final blow was struck and the government quit using silver in coins.

McCarran International Airport is named for him, not merely because he was a senator from Nevada, but because of what he did for aviation. McCarran wrote the Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938, the Federal Airport Act, and the National Aircraft Theft Act. He was the first to introduce a bill for a separate air force, in 1933.

McCarran considered himself a conservative Democrat, and opposed many of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal programs. He got out of a sickbed in 1937 to speak against Roosevelt's transparent plan to expand the nine-justice Supreme Court to as many as 15 seats. Of course, the expansion would have allowed Roosevelt up to six lifetime appointments, giving him a decisive and lasting liberal majority.

His anti-Communist fears led McCarran into an ill-advised red-hunting alliance with Sen. Joseph McCarthy. McCarran had the best-organized staff in the Senate and trusted its research. He once rose on the Senate floor to denounce a Justice Department lawyer for foot-dragging on a prosecution for subversive activity. The accusation proved unfounded. Adams figured out that one of McCarthy's ambitious aides had slipped McCarran a note, advancing the McCarthyesque rumor in the guise of fact, and that McCarran reasonably believed the note came from his own careful staff. McCarran made a public retraction.

His alliance with and defense of McCarthy, remembered today only as a lipshooting bully, permanently tarred McCarran's own reputation.

McCarran came out second-best in his feud with Las Vegas Sun publisher Herman "Hank" Greenspun. In March 1952, most important casinos simultaneously withdrew advertising from the Sun. Greenspun sued, then located a key witness to support the proposition that McCarran ordered the boycott. That forced an out-of-court settlement in early 1953. All the settlement money came from casino owners, but it cost McCarran politically. Greenspun had challenged his power, and won.

In September 1954, McCarran spoke at a Democratic rally in Hawthorne. He hammered his favorite themes of fighting Communism, and the necessity of maintaining a Democratic Senate so he could retain the chairmanship of the Judiciary Committee.

Toward the end of his speech he asked that everybody "support the Democratic Party from top to bottom."

A few moments later, he dropped dead, clutching a tiny gold box of nitroglycerine pills. The nameless International News Service correspondent who covered the speech noted that some of his last words "urged united support of the Democratic ticket, something he seldom did in the 15 years he ruled the Nevada branch of the party."

That speech was too much for his 78-year-old heart.

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full