Amid tree deaths, Mount Charleston residents want to ‘halt the salt’

It sprouted from the rocky soil of Mount Charleston before the birth of George Washington and grew to the height of a 10-story building.

Rose Meranto can hardly believe it’s gone.

For the past 30 years, Meranto lived in the shade of the towering ponderosa. It filled the small yard of her cabin on Yellow Pine Avenue, where its lowest branches cradled lights and ornaments at Christmastime.

All that’s left of it now is a stack of wood along the street and a 6-foot-tall stump a few steps from her front door.

“I’m sorry that I get emotional over the tree, but this was no insignificant thing that took place,” the 87-year-old said, fighting back tears. “It breaks my heart to see this tree gone.”

Meranto isn’t alone.

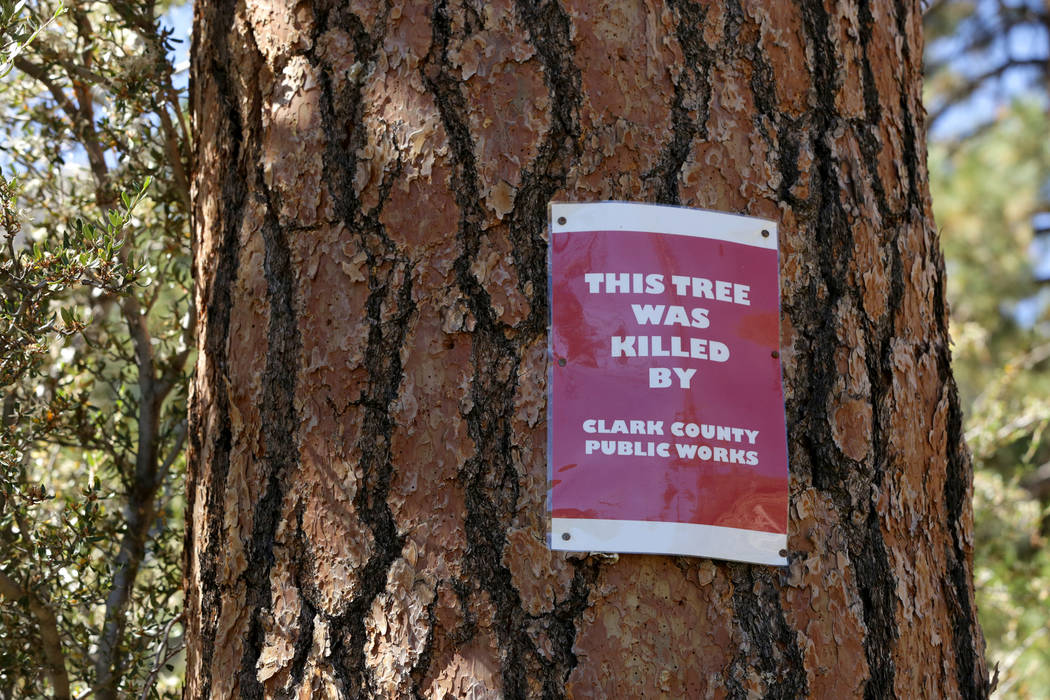

All around the Old Town neighborhood, people are lashing out over the loss of their trees. Signs nailed to some of the still-standing trunks identify the suspected culprit: “This tree was killed by Clark County Public Works.”

‘Halt the salt’

Mount Charleston residents blame salt-based, road de-icing chemicals used by county crews for poisoning their trees. If the salt doesn’t kill them outright, it weakens them, leaving them susceptible to beetles and disease. Other signs posted around Old Town urge the county to “Halt the salt.”

Jeffrey and Cynthia Silver have lost three trees so far from their 5,000-square-foot lot across the street from Meranto’s place. It cost them almost $3,000 to have the dead fir and two pines carefully cut down so they wouldn’t topple onto nearby homes, including their own.

“They were about a hundred years old. I counted the rings,” Jeffrey Silver said.

Their cabin sits next to a low spot in the road where the salty runoff from melting ice and snow collects and flows downhill to a nearby drainage channel. They want the road crews to use something more friendly to the environment like sand or cinders, even if it costs more and is less effective.

“They act like they’re doing us a favor, when it’s costing us money and the trees,” Cynthia Silver said of the county’s salt treatments. “What’s the point of living up here if you’re just sitting on a hot rock in the sun?”

County cites safety

Roughly 300 tons of de-icing salt has been sprayed on the mountain each winter since state and county road crews began using a more concentrated form of the product about six years ago.

Since then, Kyle Canyon’s water supply has experienced seasonal spikes in chloride levels, which has caused lead to leach from old plumbing fixtures in some mountain homes.

The Las Vegas Valley Water District, which operates the water system on the mountain, responded to the problem late last year by adding an anti-corrosion agent to the community’s well.

The move freed county workers to continue using salt-based chemicals on residential roads in Kyle Canyon, and that’s exactly what they intend to do this winter, said county spokesman Dan Kulin.

“Clark County, in concert with the Nevada Department of Transportation, is responsible for keeping the roads open for all motorists, including first responders like the Mount Charleston Fire Protection District, Metro and Nevada Highway Patrol,” Kulin said in an email. “As a result of extensive testing and research, it has been determined that the product currently being used on the roads provides maximum safety during and after a snow event.”

Bending to the mountain

Longtime Mount Charleston resident and advocate Tom Padden doesn’t buy it. He thinks some road departments choose salt-based chemicals because they are quicker, easier and cheaper than other snow-removal methods, though he said any honest cost analysis should also include the back-end expense of cutting down trees killed by salt along the roadway.

Right now, there is a multiyear effort underway to remove about 700 trees at risk of falling down near roads, structures and utilities on Mount Charleston. That work is expected to cost about $750,000.

“They’re spending our money to damage the forest, and they’re spending our money to clean up the damage,” said Padden, who has been calling on officials to stop using road salt on the mountain since 2012.

If protecting the public is the primary concern, he said, transportation officials should take steps to control the volume and the speed of traffic on the mountain, require chains or four-wheel-drive vehicles with snow tires when necessary, and close down the roads altogether when the weather gets bad enough.

“Don’t try to bend the mountain to your convenience. Bend yourself to the mountain,” Padden said.

It took a work crew almost three days to cut down and haul away Meranto’s dearly departed ponderosa pine. They had to take it down in sections, and someone had to scale the trunk to reach the tallest parts.

Meranto expects the final bill to come in at around $5,000. “It’s an expense I really didn’t need at my stage of the game,” she said, though the money is almost beside the point. No amount of money could ever replace what she’s lost.

“We cherish our trees on this mountain. These trees, they’re family to us, which is why we’ve been so upset to lose as many as we have,” Meranto said. “It’s just so uncalled for. We’re supposed to protect these trees.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.

Salt-free in Flagstaff

Coconino County, Arizona, stopped using salt-based de-icing chemicals on its roads in 2013 to protect the area's signature ponderosa pine trees.

Coconino County Public Works spokesman Marc Della Rocca said the county tested road salts on about 13 miles of pavement near Flagstaff as part of a five-year pilot program.

Once tree damage was documented in the test area, the county's board of supervisors voted to discontinue using road salts and go back to putting cinders on roads covered in snow and ice.

As it happens, black cinders are plentiful in Northern Arizona, which used to be one of the most volcanically active regions in the United States.

The Arizona Department of Transportation still uses brine and other salt-based products to melt snow and ice on highways in Coconino County and elsewhere in Northern Arizona.

ADOT spokesman Ryan Harding said the department employs computer-controlled spreaders and extensive operator training to limit the amount of de-icing product used and avoid environmentally sensitive areas.

The Nevada Department of Transportation also uses salt-based chemicals to clear ice from the highways on Mount Charleston, but state road crews stopped using such products last year upstream from residences in Kyle Canyon after elevated levels of chloride were detected in the community's water supply.