COVID-19 vaccine unlikely to be ‘magic bullet’ when it arrives

The COVID-19 pandemic has dashed many hopes for the fall — of returning to an actual classroom, office or even a football stadium.

One huge hope remains: that a COVID-19 vaccine will come as soon as October and with it, a return to life as we knew it before the coronavirus.

But is that hope based on reality? Many national experts suggest keeping expectations in check related to effectiveness and speed of delivery.

“I don’t think we’re going to get a magic bullet,” said Arthur L. Caplan, professor of bioethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, who wrote a 2017 book on vaccine ethics and policy.

“And I think we’re going to have to continue our behavioral efforts — the masking and distancing and quarantining and the testing and so on — in parallel with vaccination because it would be very, very surprising if we got a very highly effective vaccine first one out of the box.”

Great expectations

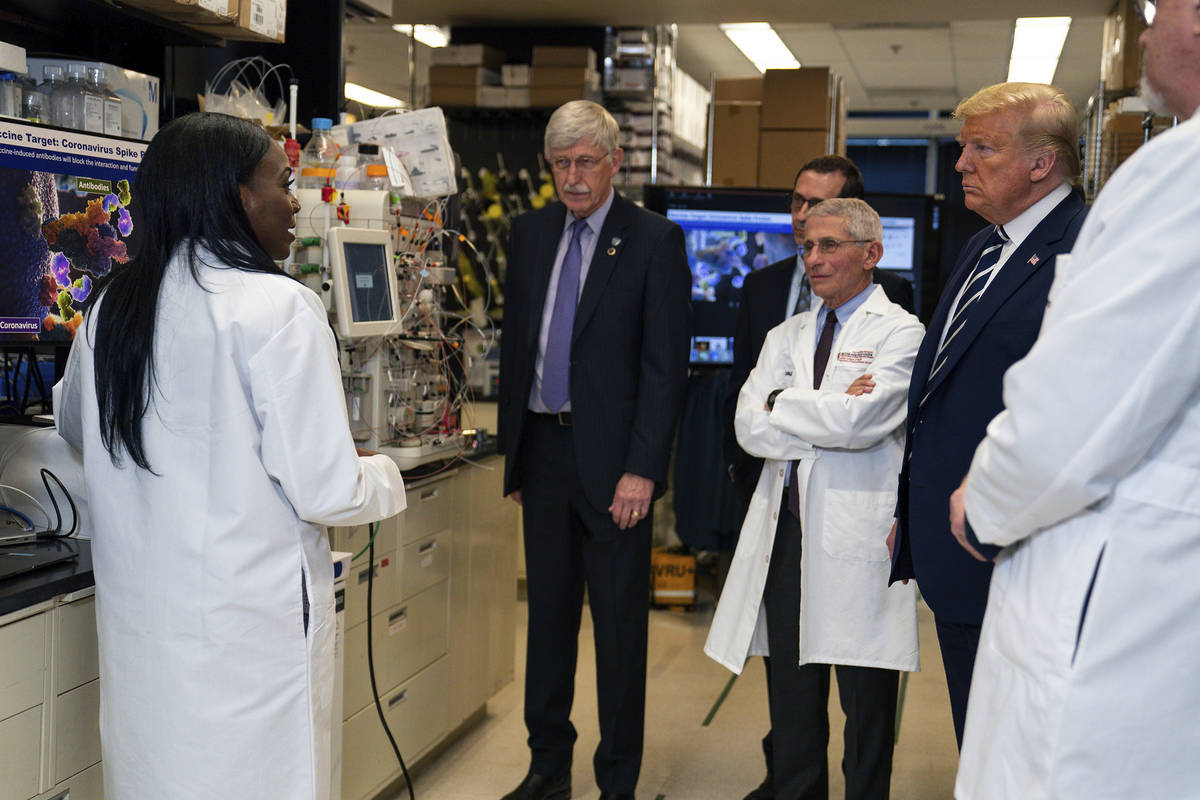

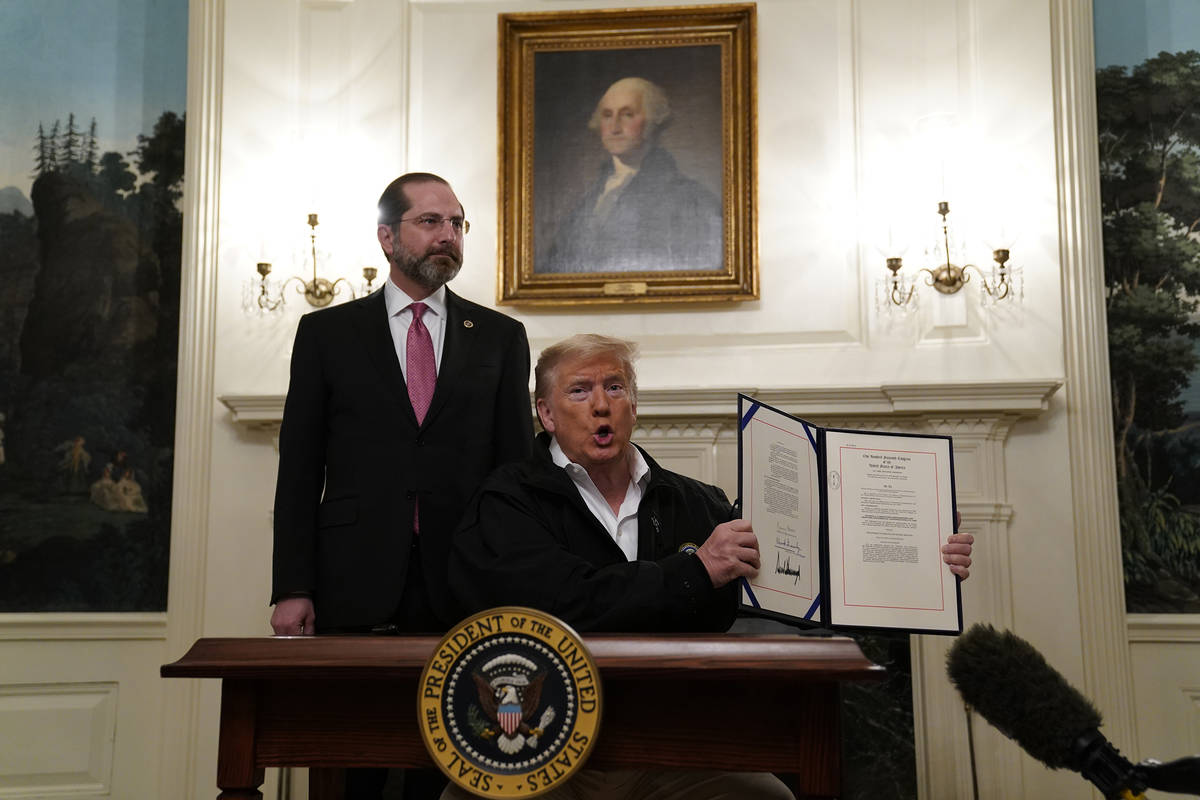

High expectations were set by President Donald Trump’s administration with Operation Warp Speed, a federal program created to hasten vaccine development. The program’s goal is to deliver 300 million doses of safe and effective vaccine, with the first doses available by January. Congress has directed almost $10 billion to the effort, funding development by private companies as well as public research.

“The administration is committed to providing free or low-cost COVID-19 countermeasures to the American people as fast as possible,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said.

Trump has predicted that a vaccine could come as soon as October, a timeline that has frequently been met with skepticism, in part because vaccines typically take many years — not months — to develop.

But there is a basis for optimism for faster results, not only because of the intense effort underway but because scientists have a head start. They already had researched vaccines for MERS and SARS, other diseases caused by the coronavirus, a family of viruses that includes the one that causes COVID-19.

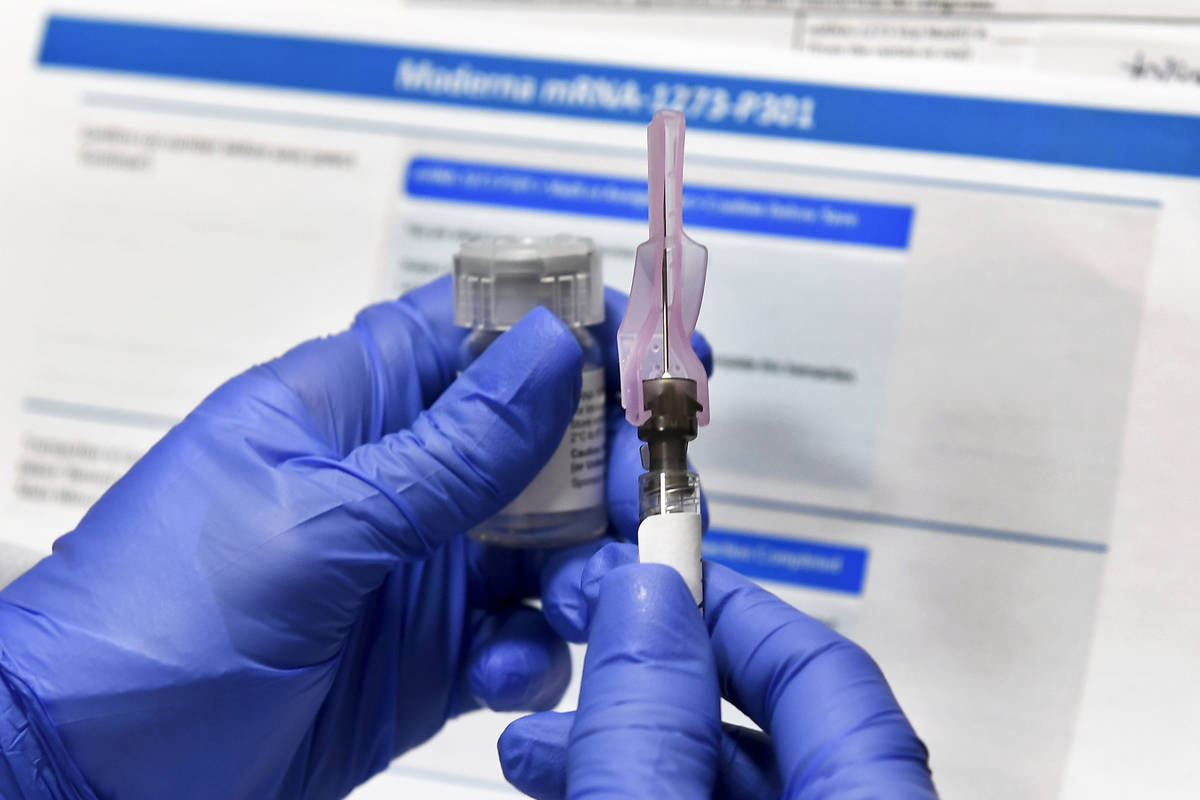

Furthermore, new technologies that rely on injecting DNA or RNA into cells, prompting the body to develop antibodies, may provide speedier routes to developing a vaccine.

“There’s never been more money or more interest or more ideas on how to make a vaccine,” said Dr. Paul A. Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and a professor of vaccinology at University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

Still, there’s no guarantee that an effective vaccine will be found.

“For those of you who’ve been on the science beat, you’ll be aware that we’re very good at curing cancer if you’re a mouse,” Caplan noted at a recent forum on vaccines conducted by the National Press Foundation. “Most of the treatments, however, do not work in humans unfortunately. So not everything pans out that looks promising in animals.”

Some COVID-19 vaccines in development have progressed to being tested on thousands of people.

At least three promising vaccines are in late-stage clinical trials. One developed by Moderna Inc. with the National Institutes of Health is being tested on 30,000 volunteers across the country, including in Las Vegas. Another is from Pfizer and BioNTech. A vaccine from AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford will resume trials following a safety review after a volunteer in a U.K. trial developed unexplained neurological symptoms.

Many winners

Rather than one single vaccine emerging from the crowd of more than 100 vaccines under development, it is more likely that multiple vaccines will roll out in a staggered fashion, some experts say. Just as there is a more potent flu vaccine for older people, there may be separate COVID-19 vaccines that work better for certain segments of the population.

“We need multiple, multiple winners here. We need vaccines for 7 billion people on this planet,” said Dr. Leonard Friedland, vice president and director of scientific and public affairs at GSK Vaccines, which has a vaccine in clinical trials. “No one manufacturer is going to be able to scale up and make enough doses for 7 billion people. So I hope they all work, and then over time, we figure out which works better in certain situations.”

The federal government has set the bar for the effectiveness for a vaccine at 50 percent, meaning it will need to prevent the disease or decrease severity in half the people receiving it. This is similar to that of the flu, another respiratory virus.

“In all likelihood this vaccine, I think, will be effective against moderate to severe disease,” Offit said. “I’d be surprised if it was highly effective against asymptomatic infection or mildly symptomatic infection.”

The bar of 50 percent effectiveness has been “roundly roasted from both sides,” said Dr. Peter Marks, a top official with the Food and Drug Administration who will play a key role in approving a potential vaccine.

“We picked that because it was a reasonable place to come out, knowing that seasonal influenza on a good year has an efficacy of about 50 percent,” said Marks, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. “It’s not perfect, but it’s something to start with.”

Some critics say that any level of effectiveness would help, while others point to the difficulty of achieving herd immunity — where enough people have immunity to a disease to significantly slow its spread — with a vaccine that only works on half of those receiving it.

‘October surprise’

When asked by the Review-Journal when he thought a vaccine might be delivered, Marks first joked that he would consult a crystal ball.

“If I had to take a wild guess, we’re looking at things probably in late fall at the earliest,” he said. “… I’m not trying to be flip about forecasting. The problem … is that there are so many variables that are going on here,” including the amount of disease circulating in areas where trials are being conducted.

“It will probably be a little bit later,” he said.

Marks, who spoke to journalists on the topic in early August, said the FDA had no intention of using an emergency use authorization “to take a vaccine of suboptimal effect or an unproven vaccine and bring it forward.”

“People need to feel confidence,” he said.

But he said the agency is relying upon expedited review times for submissions from vaccine developers and “regulatory convergence” with global counterparts to possibly shorten development timelines. But any shortcuts to bring a vaccine to market “can’t compromise safety and efficacy standards,” he added.

Offit said there has been concern expressed about an “October surprise,” where a vaccine would be unveiled by the Trump administration before Election Day, though he thought it “extremely unlikely” that there would be clear evidence of a vaccine’s efficacy by then.

“Nevertheless, President Trump has said that he expects fully that we would have a vaccine by Election Day,” he said. “I don’t see how that’s possible, unless what happens is that the administration dips their hand into Warp Speed, pulls out a couple of vaccines and says, ‘Look, we’ve tested these on thousands of people, it looks to be safe. The immune responses are great. I think that people are dying and we need to get this vaccine out there.’

“I think that would be a mistake. You want to make sure that we have clear efficacy data before we put this vaccine out there because there is a fragile vaccine confidence in this country.”

Supply chain issues

Other considerations for delivery of a vaccine include the reliability of the supply chain, which has plagued efforts to test for COVID-19.

“The nation needs to be concerned about not just the vaccine being made, but how do you get it?” said Dr. Georges C. Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “Who’s going to buy it? How do you procure it?”

In terms of transport and delivery, some vaccines require deep refrigeration of 112 degrees below zero.

“Supply line management has been a big issue,” Benjamin said. “It’s been a challenge for us around testing, around personal protective equipment. The same thing’s going to happen with this, because clearly this vaccine will require some special conditions.” Adequate supplies of syringes, vials, stoppers and alcohol swabs could become a challenge, for instance

“Remember, we’re going to be vaccinating everyone in the world, so that means just like testing, there’s going to be supply chain issues that we’ve got to work through early in the process.”

If and whena vaccine is delivered, it won’t be widely available right away.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is deliberating over “high-risk groups that should be prioritized for immunizations if a vaccine becomes available,” said Dr. Jose R. Romero, the committee’s chairman. The initial limited supply probably will be prioritized to groups such as health care providers and essential government workers, similar to recommendations made for flu pandemic vaccines, he said.

The committee, a nongovernmental group with 15 voting members, will make its recommendations to the director of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as well as the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Who gets it first?

Meanwhile, the nonprofit National Academy of Medicine recommended this month that the first to receive a vaccine should be high-risk workers in health care fields, first responders, people with certain underlying conditions that put them at significantly higher risks, and older adults living in group or overcrowded settings.

Compounding the logistics of vaccinating large numbers of people are questions of how many doses will be needed and how long protection will last. Both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines require two doses.

“Will this be a flash in the pan vaccine, a vaccine that lasts only a month or two or three or four and goes away?” Romero asked. “Or is this going to be like the flu vaccine that maybe will last six months or so and they have to get one for the next iteration? Will we need to boost periodically?”

There also is the question of whether the unknowns combined with the rush to deliver a vaccine might temper the public reception.

“You have to ask yourself even now … if the vaccine was ready today, do I want to be in line first to get it?” Benjamin said. “That’s the question we’re all going to be asking.”

Editor’s note: Many of the comments in this article were made during a series of forums on vaccines held recently by the National Press Foundation.

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0336. Follow @MaryHynes1 on Twitter.