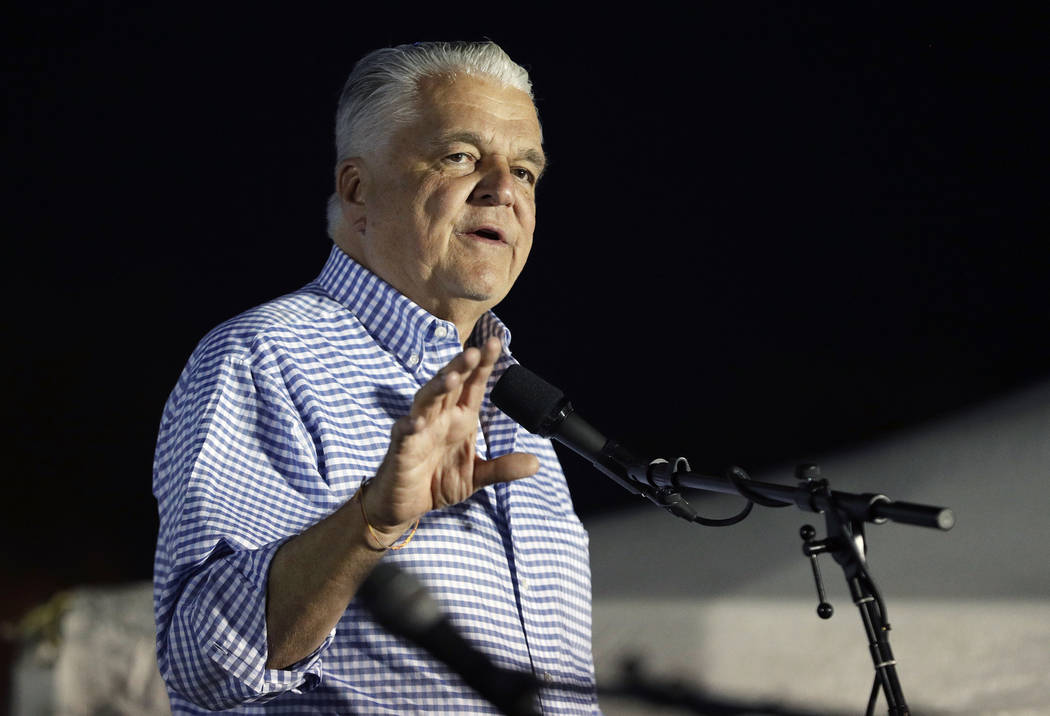

Gov. Sisolak’s campaign vow to ban assault weapons came up empty

CARSON CITY — As a candidate, Steve Sisolak promised to stand up to the powerful gun lobby and pass a slew of legislation — including banning the sale of assault rifles.

“When I’m governor, we’re going to ban assault rifles, bump stocks, silencers. We need to take action. And now’s the time to take action,” Sisolak said in a campaign ad in April 2018 that aired in Nevada’s urban cores of Las Vegas and Reno.

That call for a ban came a little over six months after the Oct. 1 shooting in Las Vegas that left 58 people dead at the Route 91 Harvest Music festival. The gunman in that shooting was armed with more than a dozen military-style semiautomatic AR-15 rifles, which were also equipped with bump stocks allowing them to simulate automatic fire.

Some of Sisolak’s promised gun control policies did become law this year, like implementing the stalled background check initiative and banning bump stocks.

But despite that promise of swift action, Sisolak’s first legislative session as governor, which saw Democrats in control of the governorship and both houses of the Legislature for the first time in 28 years, came and went without even a proposal for a ban on assault-style weapons.

The guns have once again leaped to the forefront of the national gun control debate after a week that saw three public mass shootings that left 34 people dead and dozens more wounded in Gilroy, California, El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio. Authorities said that the gunmen in the attacks legally purchased the military-style assault weapons that were used in the shootings.

In the Gilroy shooting, authorities say 19-year-old Santino William Legan evaded California’s strict gun laws by crossing into Nevada, where he was able to legally purchase a WASR 10 semiautomatic rifle, a knock-off of the military-grade AK-47.

‘Divisive’ issue in Nevada

Despite Sisolak’s campaign rhetoric, University of Nevada, Reno political science professor Eric Herzik said that he does not know “if, politically, Democrats wanted to go there during the session,” referring to an assault weapons ban.

“The issue wasn’t ready,” Herzik said. “It would have been so divisive they probably would have lost some of the other gains they made.”

But that lack of action on assault weapons from Democrats angered some gun control activists in the state, especially in the wake of the recent shootings.

“If you fear to do the thing, with regard to gun violence, that you promised to do when you were trying to get elected once you are elected, then you shouldn’t be there in the first place,” said Christiane Brown, co-president of the Northern Nevada chapter of the Brady Campaign To Prevent Gun Violence.

Brown praised the other gun control measures signed into law this year in Nevada, but said the Gilroy shooting demonstrates the “need for a national assault weapons ban.”

“States with worse gun laws can impact other states,” Brown said.

In a statement, Sisolak did not directly answer questions about an assault weapons ban, but said that since taking office “Nevada has made tremendous progress by passing the most consequential gun violence prevention legislation in our state’s history.”

“I’m proud that we passed common-sense reforms that keep guns out of the hands of those who wish to do harm,” Sisolak added. “I will continue working with law enforcement, elected and community leaders, and subject matter experts to explore different ways we can keep Nevadans safe.”

Previous bid to ban assault rifles

The federal government instituted a 10-year ban on the sale of assault rifles in 1994, but failed to extend it when it expired in 2004. Currently six states, including California, and the District of Columbia, ban the sale of assault rifles.

The most recent national poll on the issue, conducted by NPR/PBS/Marist in mid-July, showed that 57 percent of Americans support banning “the sale of semi-automatic assault guns such as the AK-47 or the AR-15,” while 41 percent oppose it.

On the national stage, many Democratic presidential candidates have voiced their support for a federal ban on the sale of the types of weapons used in the recent shootings.

In Nevada, the last attempt to ban assault weapons came in 2013 through a bill sponsored by then-Sen. Tick Segerblom, who is now a Clark County commissioner.

The bill never got a hearing and died halfway through that session.

“When you look at the list, it’s not at the very top,” Segerblom said when asked why a law banning assault weapons hasn’t passed in Nevada.

Segerblom’s comments echoed those of Democratic Speaker Jason Frierson, who told the Nevada Independent in October 2018 that he didn’t “see there being a chance” to pass such a ban, while adding that he was “open” to it.”

Frierson did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Assemblyman Ozzie Fumo, D-Las Vegas, who helped push the stronger gun storage laws that eventually became law under Assembly Bill 291, said that he was told that after passing the revamped background checks law early in the session, lawmakers “didn’t want to push too much gun legislation.”

Do bans work?

It’s impossible to say whether a ban on assault weapons in Nevada would have prevented the suspect in the Gilroy shooting from purchasing a weapon, said Adam Winkler, a UCLA law professor who studies constitutional law and gun policy.

“You can’t take any one particular act and say this law would have definitely prevented it,” Winkler said.

The effectiveness of assault weapons bans is an oft-debated topic, and data on the issue is limited.

One study from 2015 found that such bans significantly reduced deaths from mass shootings. But the nonpartisan think tank Rand Corp. wrote after reviewing the study that it didn’t meet their analysis criteria and claimed that there was “inconclusive evidence for the effect of assault weapon bans on mass shootings.”

But another study from this year, which analyzed deaths from mass shootings from 1981 to 2017, concluded that there was a significant reduction in deaths in such events during the 10-year federal ban from 1994 to 2004 as compared to the periods before and after.

Winkler said it’s still premature to say that banning assault weapons would do anything to reduce the number of mass shootings in America.

“The ultimate issue is that if you ban these weapons then clearly these weapons will show up less often at shootings. The question is if you ban them will they reduce the number of mass shootings?” Winkler said.

Pragmatic politics

Despite Sisolak’s promise, passing an assault weapons ban in Nevada would have been “an incredibly heavy lift,” according Herzik, the UNR political science professor.

Part of that reason is Nevada’s part-time Legislature, which meets for 120 days every other year.

“I don’t think they could have gotten it through, given the time constraints. … So they went for other changes, I think the most significant being the red flag warnings,” Herzik said, referencing laws that allow law enforcement to confiscate guns from people deemed to be a threat to others or themselves.

Another reason, Herzik said, was that while Democrats did control both houses and the governor’s mansion, not every Democrat may have been on board with an outright ban.

“That assumes all Democrats are on board with a very strong anti-gun agenda. I don’t think that is a safe assumption,” he said.

And just because the governor vowed to ban those weapons, he doesn’t have the power to do so on his own, Herzik added.

“It was a promise made by the governor. It wasn’t a promise made by the Legislature.”

Contact Capital Bureau Chief Colton Lochhead at clochhead@reviewjournal.com or 775-461-3820. Follow @ColtonLochhead on Twitter.