In Las Vegas and U.S., undocumented bear brunt of health care gap

When Kathia Sotelo Calderon found out that the lump on her neck was thyroid cancer, she wondered how she’d pay for treatment.

The 19-year-old undocumented immigrant from Mexico, who was brought to the U.S. by her parents when she was 7, had no health insurance. As a noncitizen, she didn’t think she was eligible for Medicaid, and she couldn’t buy a plan on the state or federal health care exchanges.

So the UNLV junior majoring in political science, now 22, did what many undocumented immigrants facing major health problems do: She got creative with fundraising and solicited family members for loans to cover the $25,000 surgery and follow-up care that she credits with saving her life.

“It’s crazy to think you could have actual cancer and not receive help,” said Sotelo Calderon, who has a scar across her neck that serves as a daily reminder of her so-far successful battle with the disease.

Health care netherworld

As lawmakers debate the best way to make health insurance affordable and available to as many Americans as possible, undocumented immigrants continue to inhabit a netherworld where health care is generally limited to emergency services and nonprofit-run clinics.

While the 2010 Affordable Care Act substantially reduced the number of Americans without health insurance — from nearly 50 million in 2010 to 28.8 million in 2017, estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed Friday — it specifically excluded undocumented immigrants from participating.

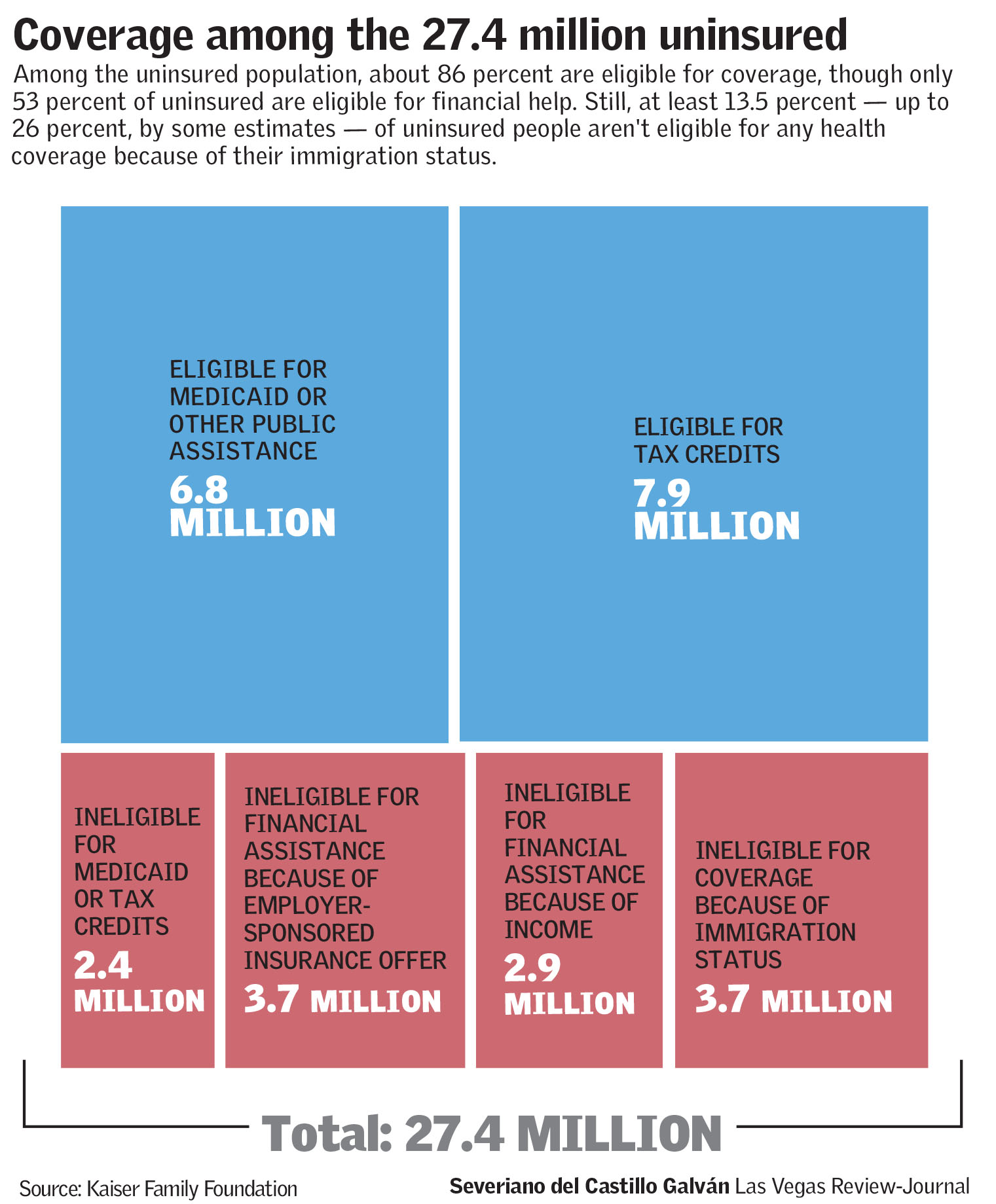

As a result, estimates by the Commonwealth Fund and the Kaiser Family Foundation now suggest that 13.5 to 26 percent of the remaining uninsured, from 3.9 million up to 7 million individuals, are foreign-born and likely undocumented.

“While the number of uninsured Latinos has fallen dramatically because of the ACA, (the undocumented) now comprise a greater share of the remaining number of uninsured adults,” according to Michelle Doty, vice president of survey research and evaluation at the Commonwealth Fund, who has studied the issue extensively.

Undocumented immigrants can legally purchase private health plans, but the expense rules that out for many. Because they aren’t eligible for ACA subsidies, the least expensive, minimum-coverage private plan a Nevadan could buy would cost more than $9,000 annually including premiums and deductibles.

There are costs to leaving a large slice of the populace without insurance.

Uninsured immigrants are often turned away by private doctors or urgent care clinics, which fear that their lack of insurance means they won’t be able to pay their bills. That means they frequently end up in hospital emergency rooms.

When they can’t pay their bills, a fairly frequent occurrence given that many undocumented people have low incomes, their treatment is generally uncompensated. That means hospital operators absorb some of the cost but pass on the rest to patients and insurers.

Some support available

Governments and taxpayers also bear some of the burden.

A Wall Street Journal survey of the 25 U.S. counties with the largest unauthorized immigrant populations in 2016 found that 20 of them, including Clark County, have programs that pay for the low-income uninsured to have doctor visits, shots, prescription drugs, lab tests and surgeries through local providers. The services usually are inexpensive or free to residents, who are told their immigration status doesn’t matter, it said.

In some states, including Nevada, undocumented individuals also are eligible for Medicaid coverage when they’re pregnant or have a life-threatening emergency. State health officials estimate that Nevada spent $39.6 million in 2015 providing such emergency Medicaid assistance to undocumented immigrants, 23 percent in state funding and the rest from the federal government.

But the government can be fickle when determining what constitutes an emergency, as Sotelo Calderon discovered when the lump on her neck began bothering her. She qualified for Medicaid emergency coverage for the tests that led to her diagnosis, but the cancer surgery wasn’t considered an emergency under Medicaid’s provisions and, as a result, wasn’t covered.

“They were telling me, ‘This cancer you have in your body isn’t an emergency,’” she recalled. “I was just kind of disgusted with the health care system.”

Instead, she turned to her community for help. With her family, Sotelo Calderon hosted a “kermes,” or festival, a 12-hour cookout in her case. That raised $4,000. Other fundraisers and borrowing eventually enabled her to pay for the operation and follow-up care.

“You never realize how big your Mexican family is until you ask for help,” she said.

Medicaid expense

About $2 billion was spent nationally on medical assistance for undocumented individuals in 2015, less than half a percent of the nation’s total health care spending of $526.7 billion that year, according to statistics from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

“For sure it is the case that some undocumented immigrants are getting services,” said Leighton Ku, director of the Center for Health Policy Research at George Washington University. “It’s not free; $2 billion is something. On the other hand, as a share of all Medicaid expenditures it’s pretty darn small.”

The cost of adding undocumented immigrants to the U.S. public health care system has pre-empted any political solution being put forward. But just what that cost would be is open to debate.

The Center for Immigration Studies, a nonprofit that supports lower levels of legal immigration, estimated in 2010 that it would cost $8.1 billion a year to cover the 3.1 million undocumented immigrants that it calculated would be eligible for Medicaid at the time.

Ku, however, said that estimate is likely “way too high.” It assumes 100 percent Medicaid participation, which is unrealistic even among citizens, it doesn’t count the $2 billion already being spent, and it estimates per capita costs based on Medicaid enrollees, though research shows immigrants’ health costs per capita fall below those of U.S. citizens.

Wendy Parmet, a law professor at Northeastern University in Boston and director of the Center for Health Policy and Law there, said it’s important for lawmakers to devise a solution to bring at least DACA participants into the health care system.

Doing so could even help stabilize the Affordable Care Act’s health care exchanges, said Ku. If undocumented immigrants were given access to the insurance exchange sans subsidies, that could bring down costs for citizens purchasing off the marketplace, he said.

Funding at risk

For now, the undocumented population as part of the uninsured faces a more immediate threat: an uncertain future for the nonprofit community health centers, which provide about 28 percent of care nationwide to uninsured individuals, according to the National Association of Community Health Centers. Federal funding ran out Sept. 30 and has not yet been renewed.

Sotelo Calderon is one of the millions of undocumented immigrants nervously watching events unfold in Washington.

Her health care situation has improved since her health crisis. Being able to participate in DACA provided her with employer-sponsored health care when she landed a full-time job in August. But with the Trump administration’s subsequent decision to rescind DACA as of March 2018, she’s not sure what she’ll do from there if no political solution emerges.

“There comes a point in time when you’re going to need (health insurance), and life is really scary when you find out how important it is,” Sotelo Calderon said.

Contact Jessie Bekker at jbekker@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow @jessiebekks on Twitter.

Public insurance available in some states

Some states, including California and New York, make public health insurance available to DACA participants and undocumented individuals, though Nevada does not.

Under California's state Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, DACA participants with qualifying incomes can receive full coverage. Those who are undocumented and have qualifying incomes also can get limited or emergency Medi-Cal.