Colorado offers cautionary lessons as Nevada studies legalizing recreational pot use

DENVER — Just beyond the Rocky Mountains, an industry that once conjured images of dank basements and back-alley deals is blossoming under state regulation.

After a sluggish start in sales following the 2012 vote to decriminalize marijuana, Colorado’s pot trade — and corresponding tax revenue — is booming as consumers from within and outside the state flock to cannabis shops.

Some predictions made during the campaign by legalization supporters have proved true: Fewer people are being arrested. And despite initial fears that legalization would cause a rampant increase in drug use among Colorado’s youth, teens aren’t smoking more weed, according to the state Department of Public Health and Environment.

But Colorado’s first-in-the-nation dive into a legal pot market also has come with unanticipated problems and failed predictions:

■ Rather than eliminate the black market, legalization of marijuana has helped it flourish, police say.

■ Citations for driving under the influence of pot have made up a bigger portion of DUIs every year since legalization, even as total DUI numbers have dropped.

■ Edible marijuana products were rarely talked about during the Colorado campaign, but they quickly became a headache for lawmakers and hospitals alike.

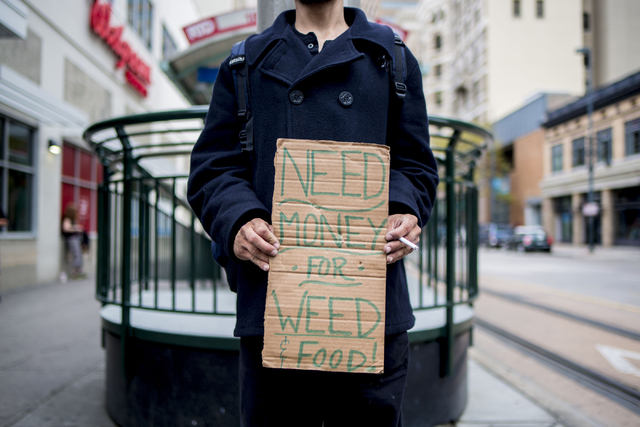

■ While Colorado’s tourism industry continues to boom, some are linking legal weed to an increase in the homeless population in Denver, which has drawn concerns from downtown convention groups.

■ And some residents of one Colorado community have had enough — and have forced a vote on whether to shut down recreational pot stores in their city.

“Neither side has been exactly right” about legalization’s consequences, said Colorado state Sen. Pat Steadman, who voted for it. “But by and large, all the horrible things that the opponents were afraid of have not come to pass. The sky didn’t fall.”

Still, Colorado’s experience provides plenty of lessons — some cautionary, some encouraging — for voters in Nevada and four other states considering legalizing weed in the Nov. 8 election. A Las Vegas Review-Journal reporter and photographer spent a week in Denver to find out how legalization has affected Colorado and how it might affect Nevada if Question 2 passes.

BLACK MARKET THRIVES

Much like their Colorado counterparts did in 2012, Nevada supporters predict legalizing pot will dry up the illegal drug market.

But after 2½ years of legal sales, Colorado law enforcement officials said the black market is not only still alive, but thriving.

“We’ve seen nothing but black market problems flourishing,” said Jim Gerhardt, vice president of the Colorado Drug Investigators Association. “Marijuana is something people can grow in their home. Little tiny amounts of that can be worth hundreds and thousands of dollars. And really, legalization hasn’t changed any of that.”

Part of the problem, Gerhardt said, is the high price of legal marijuana.

With all the sales, excise and other special taxes mixed in, recreational marijuana bought in Colorado typically carries around a 30 percent tax. So the purchase of a $150 ounce of marijuana at a retail shop can end up costing consumers close to $200.

Gerhardt said that same quality of pot sells for closer to $100 on the street.

Another issue involves growing marijuana. Colorado’s medical marijuana law allows cardholders to grow plants for their use. A cardholder also can act as a “caretaker” for other patients and grow up to 99 plants per patient.

As a result, the amount of marijuana seized in illegal grow cases has skyrocketed.

Denver police seized 524 pounds of marijuana in 2013, the first year it was decriminalized, according to city data. The next year, when retail shops opened, they seized 9,504 pounds. Last year saw a 50 percent drop, with police seizing 4,738 pounds — still well above the 2013 level.

Denver District Attorney Mitch Morrissey said growers are moving to Colorado from across the United States and shipping their products out of the state.

“We’re seeing the products from this state go all over the United States,” he said.

The issue boiled over in December 2014 when neighboring states Nebraska and Oklahoma sued, alleging the flow of weed through their states was facilitated by legal marijuana sales in Colorado. The lawsuit was dismissed by the U.S. Supreme Court in March.

Whether Nevada will see a similar issue arise with home-grows is uncertain. Nevada doesn’t have the same “caretaker” law that has helped fuel the black and gray markets in Colorado.

POLICING POT

Much like the current Nevada campaign, marijuana supporters in Colorado pushed the idea that legalizing the drug would result in fewer people going to jail or prison for possession. And after initial returns, they were right.

Marijuana possession arrests in Colorado plummeted after legalization, dropping by 47 percent from 2012 to 2014, according to the Department of Public Safety. The state’s law allows for possession of less than 1 ounce of pot.

Meanwhile, court filings related to weed — mostly citations that can add up to big fines, bench warrants and often jail time — dropped by 81 percent in that same time.

“I think the real reason to talk about (legalizing marijuana) is for criminal justice reasons,” said Colorado’s Director of Marijuana Coordination Andrew Freedman. “It’s been heartening to see those numbers go down.”

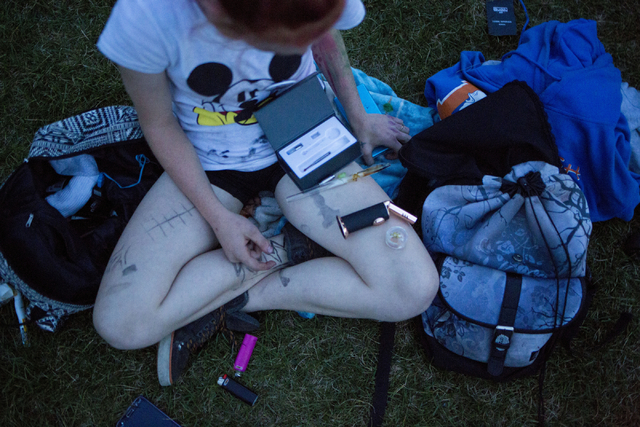

While growing and possessing pot are legal in Colorado, any form of public consumption remains illegal.

But that hasn’t stopped plenty of people from doing just that.

Anyone who takes a walk down the 16th Street Mall in downtown Denver — a mile-long, open-air pedestrian mall — won’t have to look, or sniff, for long before stumbling upon someone using marijuana. The parks, especially those near downtown, are notorious for public pot use.

Denver police cited about 760 people for using marijuana in public in both 2014 and 2015, the first years the city tracked that data.

Gerhardt said some of those cited are residents or tourists who are simply ignorant of the law. But others know full well that it’s not allowed, he said.

“There are a lot of those people who do it in open defiance of the law,” Gerhardt said.

Dan Rowland, a city spokesman speaking on behalf of the Denver Police Department, said police are actively enforcing the consumption law, but noted that it’s not the highest priority for police.

“Its obviously something that they’re aware of and keeping an eye out for,” Rowland said. “But it’s not something where our police are doing big, coordinated operations the way they would enforce more dangerous crimes that affect public health and safety.”

DRIVING WHILE STONED

One of Nevadans’ biggest concerns about legalizing marijuana involves driving while stoned. Opponents say the drug’s increased availability would cause more people to drive high and make the roads more dangerous.

So far in Colorado, the picture is mixed: Total DUIs have declined since the start of 2014, but marijuana-related DUIs make up a slightly larger share.

Colorado State Police issued 18 percent fewer citations for DUIs in 2015 (4,546) than 2014 (5,546), according to department data.

Alcohol-related DUIs made up the vast majority both years, but the share of pot-related DUIs rose from 12.2 percent in 2014 to 14.6 percent in 2015.

And this year, marijuana DUIs are trending at a much higher rate, accounting for about one-quarter of all DUI citations in 2016, according to State Police Sgt. Rob Madden.

But Madden said he doesn’t think people are driving stoned more often. Instead, he said state police officers are better trained to spot marijuana impairment in drivers.

Madden said troopers have learned more advanced detection techniques, such as looking at breathing patterns and skin conditions.

“They’re missing less,” he said.

POT’S TOURISM IMPACT

Then there is the potential impact on tourism, Nevada’s biggest industry. Could legal pot turn away a significant number of the more than 42 million visitors who came to the Las Vegas Valley in 2015?

Visit Denver, the local government’s marketing arm, put together a scathing report in December 2015 after receiving several complaints from convention planners about the conditions in the downtown area.

Most of the complaints referred to the visible homeless population, public marijuana use and overall conditions at the 16th Street Mall.

In emails to Visit Denver, planners called the area “dirty,” “smelly” and “depressing,” and said they were taking their conventions elsewhere.

“The neighborhood had way too many vagrants. I don’t remember Denver being that bad,” one read.

“This client does a lot of business in Denver and was disappointed to see, in his opinion, how things have changed in the city since marijuana was legalized. He says he sees lots of people walking around looking ‘out of it’ and does not want to expose his attendees to this. I hope you don’t mind the honesty but I wanted you to know exactly ‘why,’” another email read.

Josh Gappelt, director of emergency services at the downtown Denver Rescue Mission near the mall, said there has been a marked increase in the number of homeless people coming through the shelter’s doors since the 2012 vote.

Gappelt believes that legalized marijuana has had a direct impact on the number of homeless people in downtown Denver. Many homeless living in surrounding states where pot is illegal have moved to Denver as a sort of self-preservation because simply carrying marijuana isn’t a crime, he said.

But legal weed is just one of several factors that has made the area attractive to the homeless population, Gappelt said.

“There’s a lot of reasons people in poverty are moving to Colorado,” he said.

For one, in 2014 Colorado expanded its state-funded Medicaid program, making it easier for indigent and homeless people to see a doctor and receive health care, Gappelt said.

While Denver has received anecdotal complaints about marijuana and downtown conditions, its tourism industry — as well as the state’s — has flourished since pot became legal.

Denver attracted a record 16.4 million overnight visitors in 2015, up almost exactly 1 million over the prior year. Meanwhile, Colorado — considered one of the top outdoor recreation destinations in the United States — drew 77.7 million visitors who spent $19.1 billion in 2015, up nearly 7 percent from the prior year.

POT OVERDOSE DANGER

If there is one aspect that took Colorado by surprise, it was the immediate draw of consumers to the edible marijuana market.

Because people can’t smoke in public and tourists can’t smoke in their hotel rooms, being able to eat the drug “became a sort of easy way for them to get around that problem,” said Sam Kamin, professor of marijuana and criminal justice law and policy at the University of Denver.

Lawmakers crafted some regulations for edible products on packaging, dosage recommendations and THC strength, but those proved to be insufficient, Kamin said. THC is the substance in pot that gets people high.

The result? A significant spike in hospitalizations related to marijuana.

According to the Colorado Hospital Association, the state had 1,440 pot-related hospitalizations per 100,000 people from 2010 to 2013. That rate jumped to 2,413 per 100,000 for 2014-15. But unlike other drugs such as heroin, prescription painkillers or even alcohol, there have been no deaths reported from marijuana overdoses.

Kamin recalled one of the first edible products he saw on the market: a gummy bear loaded with 60 milligrams of THC.

“At 10 milligrams per dose, you’re supposed to cut the gummy bear into six pieces,” Kamin said. “No one is actually doing that.”

But Kamin said lawmakers have worked to increase the awareness of the dosages. Colorado Attorney General Cynthia Coffman approved a series of new rules in November 2015 that forced all edibles to be broken up into 10 millogram pieces.

“That’s a much more user-friendly product,” he said. “People can still take too much of that, but they have to be a lot more willfully blind to the information that’s coming at them.”

The other issue with edibles came in the form of children getting their hands on a tasty looking brownie that wasn’t intended for them.

A study in the Sept. 6 edition of the Journal of the American Medical Association looked at 163 marijuana exposure cases reported at a single pediatric hospital in Aurora, Colorado, from Jan. 1, 2009, to Dec. 31, 2015. Aurora is a Denver suburb of more than 346,000 people.

The study found that nine cases were reported in 2009. By 2015, that number was 47.

More than half of those cases involved children eating an edible marijuana product, the study found.

Kamin said it’s hard to know for sure if this is really a new development. Because edible marijuana is legal, Kamin said, parents may be more willing to admit that their child got into their pot brownie than they were in the past.

Nevada state Sen. Patricia Farley, R-Las Vegas, is aware of this danger and plans to introduce legislation in 2017 that would be stronger than Colorado’s. Farley said manufacturers of edibles in Nevada have agreed to stop making foods that could “in anyway seem attractive to kids,” such as gummy bears or packaging that uses cartoon characters.

WEED IN THE WORKPLACE

In the months after legalization, employers big and small scrambled to figure out how to deal with it.

Companies across the board were drug testing more often but mainly focused on the pre-employment test, said attorney Curtis Graves at Mountain States Employees Council, a Denver organization that provides human resources help to more than 3,000 companies.

Since then, several companies have softened their position, especially those in the hospitality and tourism field at the state’s massive ski resorts, Graves said.

A majority of the seasonal tourism workforce is made up of younger employees who would struggle to pass those pre-employment tests, he said, so companies needed to adjust or risk being short on workers.

Some have found drug-testing companies that don’t screen for THC, while others have stopped the pre-employment test all together.

“The economic reality is that employers have had to loosen up because they have business to run,” Graves said.

But other industries have gone the other way and have strengthened their zero-tolerance drug policy, said Tiffany Baker, co-owner of the Denver DNA and Drug Center, which provides drug testing services to dozens of companies in the Denver area.

Baker’s company handles drug testing for approximately 70 different driving companies, from school bus drivers to long-haul logistics. Those companies, Baker said, have gone beyond the pre-employment tests and are conducting random drug tests on drivers every three to four months to ensure that they are not a danger.

If the tests come back positive, the employee typically gets fired, even though the drug is technically legal under state law, she added.

That is because a Colorado Supreme Court decision last year held up Dish Network’s firing of a quadriplegic customer service worker in 2010 for failing a company drug test.

The worker, Brandon Coats, sued to get his job back, but his bid failed at both the trial court and state Supreme Court. The courts cited the fact that the drug is still illegal on a federal level, and employees can be fired for having it in their system.

LEGALIZATION NOT A PANACEA

Kamin believes the rollout of legal marijuana has been a relative success, but he cautioned that people from other states should not vote to legalize pot solely on the idea of a tax revenue windfall.

“You shouldn’t do it to get your state rich,” he said.

Marijuana sales in Colorado are heavily taxed, hovering around 30 percent depending on the individual municipality.

In 2014, the first year of legal pot, tax revenue fell far below the numbers projected by legalization supporters, bringing in just $76 million.

But the numbers have been climbing in the years since. Sales reached almost $1 billion in 2015 and generated $135 million in tax revenue, according to the state. And through the first seven months of 2016, Colorado had collected $105.8 million in taxes, according to the state Department of Revenue.

The first $40 million collected from a 15 percent excise tax is earmarked for education, which was one of the biggest promises supporters made. But 2016 is the first year the state is actually expected to hit that mark.

In the grand scheme, tax revenue from marijuana makes up a fraction of Colorado’s budget, accounting for just over 1 percent of the state’s $10.36 billion general fund.

“It’s not game-changing money for a state given the size of our state budget. That’s a relatively small piece,” Kamin said. “But it is $135 million in tax revenue that wouldn’t have otherwise come in.”

About $8 million of that goes back to fund the agency that regulates and licenses marijuana businesses. But bigger chunks of $30 million each have gone back into the community, helping fund youth drug and alcohol prevention programs and subsidizing some of the state’s substance abuse programs.

In Nevada, legal pot supporters are projecting smaller tax gains. The Coalition to Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol has said legalizing weed would bring in roughly $20 million annually for schools through a similar 15 percent excise tax and $60 million in total taxes annually — just over 1 percent of the state’s general fund.

IMPACT ON YOUNG USERS

Opponents of legalization in Nevada argue that decriminalizing marijuana will make the drug more accessible to children and cause more teenagers to smoke it.

But those fears, which opponents also raised during the 2012 campaign in Colorado, have not manifested.

Colorado has tried to monitor teen marijuana usage as part of its biennial Healthy Kids Colorado survey, an anonymous, voluntary survey that received 17,000 responses in 2015.

The survey found that teen use has remained nearly unchanged and has been trending down since 2009.

In 2015, 21 percent of Colorado teens reported using marijuana in the past 30 days, which was slightly below the national average. In the 2009 survey, that number was 25 percent.

Meanwhile, the rate of expulsions for drugs in Colorado schools has fluctuated since 2008, thus giving no definitive data, according to a report from the Colorado Department of Public Safety.

But as Steadman, the state senator, notes: “Its not like marijuana legalization is what caused marijuana to be found on a school playground. It was there before.”

OTHER STATES, OTHER VOTES

Nevada isn’t the only state voting on legalized marijuana in November. California, Arizona, Maine and Massachusetts have similar ballot measures. And all five states are eyeing the effects in Colorado.

A different vote will take place in one southern Colorado community whose residents will decide whether or not to close up the recreational pot shops. Under Colorado law, individual communities have the power to opt-out of the marijuana industry and ban pot shops, cultivation and manufacturing facilities.

The group Citizens for a Healthy Pueblo, gathered enough signatures to put the issue on November’s ballot for both the city and unincorporated communities in Pueblo. If the measure passes, recreational marijuana shops would have one year to close, but residents still would be able to grow, possess and use pot.

Pueblo County Commissioner Sal Pace argues that the move won’t rid the county of marijuana and would only kill an industry that brought life back into an industrial community that has ranked last in jobless and poverty rates among the state’s six major Metro areas in most years since the Great Recession.

“Realistically, marijuana’s gonna be here whether this passes or not,” he said.

Pace said the marijuana industry — whether it’s the 1,300 jobs in the cannabis industry or jobs in construction where marijuana projects make up 40 percent of all work — has helped cut the county’s jobless rate by more than 50 percent. “We can’t afford to go backwards,” he said. “It’d be devastating.”

But Paula McPheeters, a member of Citizens for a Healthy Pueblo, said it feels like her town has become inundated by the marijuana industry, and she doesn’t want her community to be known for it.

For her, the issue came to a head when she saw a marijuana store less than a mile from her son’s school.

“We want our say. We know we have that option,” McPheeters said. “But whatever the outcome of the vote, it’s been a success.”

McPheeters also believes that voters didn’t know what they were getting themselves into when the amendment legalizing marijuana passed in 2012.

“We didn’t know what we were voting on, to be honest.”

Contact Colton Lochhead at clochhead@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4638. Follow @ColtonLochhead on Twitter.