Nevadans with misdemeanor pot convictions want records expunged

Nevadans with past misdemeanor pot convictions can have their records sealed away, but the Clark County district attorney isn’t ready to wave a magic wand to make it happen.

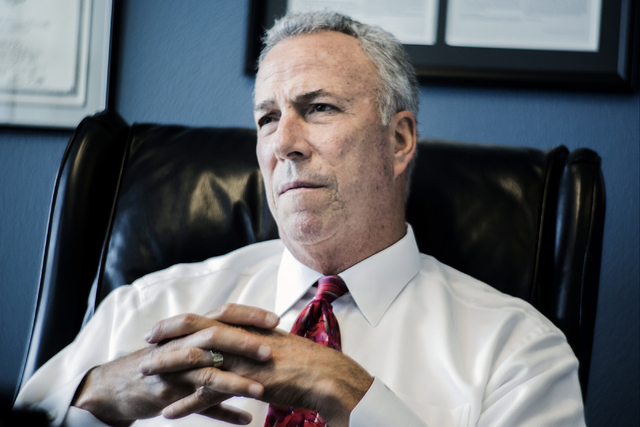

“I’m not going to take an active role in seeking the vacation or seeking the dismissals,” Clark County District Attorney Steve Wolfson said in a recent interview.

That’s a different approach than several other jurisdictions have been taking.

Since January, a cascade of cities and counties up and down the West Coast, including San Francisco, San Diego and Seattle, have announced plans to erase or reduce nonviolent marijuana convictions.

The argument for such moves is that in states that have legalized recreational marijuana, people are still stuck with past pot convictions, hurting their employment and housing opportunities, for the same thing that now rakes in millions for businesses and states.

“The district attorney clearly has more than one option at his fingertips that would allow him to establish justice for these people,” said Myesha Braden, director of the Criminal Justice Project for the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “It’s most unfortunate that he is not willing to do so.”

The Lawyers’ Committee this month sent out a call to action urging prosecutors in cannabis-legal states to expunge the records of people convicted on misdemeanor marijuana possession charges.

“Individuals with marijuana convictions, particularly for amounts that are now legal to carry, are carrying a tremendous burden when it comes to finding employment, finding housing,” Braden said. “They are paying a cost that they will continue to pay as long as that conviction is on their record.”

Wolfson said he came to his decision on the issue after researching what communities such as Seattle and San Francisco did, speaking to people within his office and reviewing recent changes to Nevada laws regarding record sealing.

Two laws passed in last year’s Legislature that shortened the amount of time someone convicted of a misdemeanor must wait before being able to ask the court to seal their record, reducing that timeframe to just one year after the sentence is completed.

“What I’ve found and experienced is that the single most important reason people want their cases sealed is employment,” Wolfson said. “Now our Legislature has made it much easier and quicker to have records seal.”

“If someone files such a petition or motion, we will review those on a case by case basis,” Wolfson added, noting that his office routinely handles such requests on varying types of cases.

State’s take

The lawyers for the Nevada Legislature say that district attorneys in Nevada don’t have the authority to do what Holmes and other prosecutors have done, however.

State Sen. Tick Segerblom asked the Legislative Counsel Bureau last month if prosecutors in Nevada had the ability to mass-petition courts on behalf of convicted Nevadans in order to vacate or seal those old marijuana convictions.

The answer?

No.

“They looked into the issue and found that, while Nevada’s and California’s laws are somewhat similar in that both allow a person to request a court to seal their past criminal records relating to marijuana crimes, nothing in Nevada’s laws would authorize a district attorney to seal those records on their own,” Segerblom told the Review-Journal.

Part of the reasoning was Gov. Brian Sandoval’s vetoing of Assembly Bill 259 from the 2017 Legislature.

That proposal, sponsored by Assemblyman William McCurdy, D-Las Vegas, would have allowed people with convictions for possessing less than an ounce of marijuana — the limit that is now legal to possess — to ask Nevada courts to clear and seal those records.

The bill passed on party lines, with every Republican in both chambers voting against it. Sandoval vetoed the bill, but said in doing so that there “is much to commend” in the proposal.

“Individuals with prior convictions for possession of marijuana in amounts now legal in Nevada should be able to get their criminal records cleared expeditiously,” Sandoval wrote.

But Sandoval argued that the overall bill was too broad, noting that it made other changes to state laws dealing with record-sealing and minimum prison sentences.

The governor noted that the Legislature had already passed laws reducing the amount of time that must pass to seal records, and that Nevadans looking to clear marijuana convictions could use that process — a view that seems to line up with Wolfson’s.

“To the extent that there are individuals suffering under criminal records for conduct now legal in Nevada, those cases are best handled on a case-by-case basis,” Sandoval added.

McCurdy’s bill still has a chance to become law in 2019, because it was one of 15 bills vetoed after the session ended that has the chance to return in next year’s Legislature.

Contact Colton Lochhead at clochhead@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4638. Follow @ColtonLochhead on Twitter.