School program inspires students to be ‘like Josh’

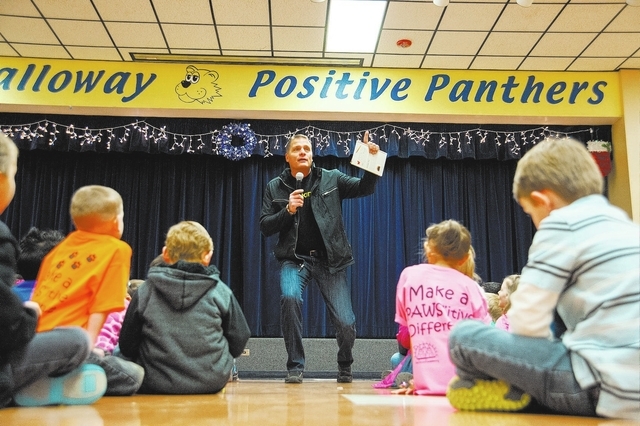

It’s a Friday morning at Galloway Elementary School in Henderson, and Drew Stevens waits as students file into the room and sit cross-legged on the floor.

Many have heard him speak before so, after an introduction by the principal, he doesn’t dwell on the event that led to this assembly: On Sept. 5, 2008, his 12-year-old son, Josh, died in a terrible accident.

Drew chokes up on the word “accident.” In five years, this hasn’t gotten any easier.

He shares an anecdote about the kindness Josh once showed to another boy on the football field, then transitions into what he has come to discuss with these third-, fourth- and fifth-graders: their legacy.

“Your legacy is being created — whether you know it or not — right now, by the way you treat other people,” he says.

He asks fifth-graders, specifically, to consider how they will be remembered at Galloway after they go to middle school.

“What will they say about you?”

He asks how many want to be remembered for making Galloway a better place, and hands shoot up in the air. Many wear T-shirts that read, “Be Kind … like Josh.”

Drew Stevens has given versions of his talk more than 700 times since he and his wife, Barbara, created the Josh Stevens Foundation in 2009. He estimates that 300,000 people have heard his message.

After their son’s death, the Stevenses were struck by the number of people who came forward with stories about Josh’s big heart. Those stories inspired the foundation’s mission: “to recognize and reward heartfelt kind acts, and to inspire more kindness, more often.”

Miller Middle School and the Paseo Verde Little League immediately embraced the concept. Josh, who loved sports, was a seventh-grader at Miller when he died.

Since then, about 350 schools in Nevada, California, Oregon, Washington, Minnesota, Florida and Mississippi have joined. In Clark County, 155 schools have welcomed the program, which is also used in the Henderson Parks and Recreation Department.

A year ago, the foundation, which has an annual budget of $350,000, hired Jennifer Morss as executive director.

“Up until that point, it had really been family and friends that had been running the organization,” Morss said. “I have never seen a nonprofit where there is this total outpouring of love.”

She said Drew Stevens was tickled to learn a Google search for “be kind” shows the Josh Stevens Foundation as the top result.

Schools cover the cost of the program by selling $10 T-shirts with the “Be Kind” message to their students.

At Galloway, T-shirts were flying off the shelf before school started on the December day that Drew Stevens spoke. Students are urged to wear them every Monday.

The school mascot is a “positive panther,” so the slogan on the back of Galloway’s “Be Kind” shirts reads, “Make a ‘Paws’itive Difference,” and shirts come in several bright colors.

“Our whole theme is colors this year; that’s why we have all the different colors,” principal Maureen Langenbach said.

This is the third year Langenbach has used the “Be Kind” program at Galloway. She likes it because it is “genuine.”

“It’s just not something that’s scripted. It’s real talk with real kids.”

While the issue of bullying has become a prominent topic at schools, Langenbach said, she prefers “to look at the positive side of things.”

She might ask a student: “Was that kind?” or “What can you do that would be kind?”

“It’s actually transitioning over to real-life experiences and how we expect others to behave in the real world,” Langenbach said.

Drew Stevens always conducts the kickoff assemblies himself.

Schools then are armed with lime green “BE KIND … LIKE JOSH” bracelets. Students caught being kind throughout the year are rewarded with a bracelet and a call to a parent. Hundreds of thousands of children have been caught committing acts of kindness.

“I’m telling you, since this (started), I have the kindest kids,” Langenbach said.

Morss said Drew Stevens initially spoke twice a year at each school, first at a staff meeting and then at a student assembly. As participation increased, that became more emotionally and physically difficult for Drew, who has two other children and also is part owner of Glove Connection, a safety supply business based in Henderson.

“He would be speaking 600 times a year and sharing the story of Josh,” Morss said.

Drew reluctantly agreed to appear on a DVD now shown at staff meetings conducted by Morss. “We had to look at it realistically as we continued to grow. Drew’s just one person.”

During a recent interview at his Glove Connection office, Drew explained why he continues to deliver the “Be Kind” message to students in person.

“I want these kids to attach a story to the meaning of these words,” he said.

He believes the story of the way Josh lived his life, and of his family’s struggle with his loss, resonates with children.

“I don’t know why, but I’ve seen it, and it’s beautiful,” he said.

Asked to share his favorite “Be Kind” story, Drew described an encounter with an eighth-grader in Northern Nevada who approached him after an assembly.

Drew said the boy was his size, about 6 feet 3 inches tall and 200 pounds, and looked disheveled. Wanting to talk in private, he waited for dozens of others to disperse. Then he began to cry.

“The bullying at this school stops today,” the boy told him. “It’s over.”

Drew wondered how he could make such a statement, and the boy told him, “I’m the guy.”

Even his teachers feared him, he said.

Then the confessed bully told Drew, “I hit the reset button on my heart today.”

They cried together, and Drew told the boy he would check on him in the future. School administrators later told Drew the boy had become a “different kid.”

Drew has plenty of other stories about meaningful moments experienced with children during his school visits.

“I don’t want anybody to ever think that I don’t recognize the blessing in this,” Drew said. But he dispels any notion that his foundation work has helped him heal. He remains, by his own description, “broken.”

“This journey is just incredibly difficult, every minute of every single day,” Drew said.

Yes, he must relive his son’s death daily during school appearances, but he constantly thinks about the loss anyway. Speaking about Josh’s death is like thinking out loud, he said. “I’m covered in it. I’m consumed by it.”

Josh had tears in his eyes as he headed off to school for the last time. He was having difficulty adjusting after returning to school that fall.

His father wanted to give him something to look forward to, and asked what he could do. Drew already knew what the answer would be. Josh had enjoyed riding around their new neighborhood, Anthem Country Club, in a borrowed golf cart and wanted the family to have one.

Drew already had bought one and told Josh it would be waiting in the driveway when he returned from school.

After dark that night, the father and son cruised around the neighborhood. As they reached the top of a hill, neighbors called “hello,” and they turned to wave.

Drew recalls having his eyes off the road for a “fraction of a second too long.” When he turned back, he saw an illegally parked boat in front of him and swerved left to miss it. Josh was thrown out of the right side of the cart.

Drew expected to find his son with a skinned elbow or a bruised knee, but there wasn’t a mark on his body, just a lump on his neck.

Yet Josh wasn’t moving. He had hit the boat’s swim deck, severing his carotid artery and causing internal bleeding.

Josh died in his father’s arms, one month before his 13th birthday. “I still just sit in my house and think: How the hell did this happen?” Drew said.

Mehdi Zarhloul, owner of Crazy Pita restaurant, was looking through the newspaper’s obituary section when Josh Stevens’ picture caught his eye.

“The whole restaurant, when I showed them, all my staff stopped,” he recalled.

Despite the lunch rush, he and his manager left to visit the Stevenses, who were regulars at his restaurant since he opened on Horizon Ridge Parkway in 2006. He moved it to The District at Green Valley Ranch in 2007.

Zarhloul recalls Josh coming through the door with a big smile, calling out, “Hey, Mehdi,” and starting in on one of his stories.

“He brightens the room,” Zarhloul said. “As soon as he walks in, the staff starts smiling. I start smiling.”

And Josh always was jumping in to help others at the restaurant.

“That’s how I connected with him, because that’s what I do for a living. I’m in the service industry,” said Zarhloul, who expected Josh to someday want a part-time or summer job.

Zarhloul donated most of his office space on Green Valley Parkway to the foundation and began selling T-shirts in his restaurant. All the proceeds go to the foundation, for which he is treasurer.

Zarhloul said he also has incorporated the kindness philosophy into his employee standards, encouraging his workers to smile and make eye contact with customers, for example.

He sponsors an annual Josh Stevens Day in honor of the boy who loved kefta pitas, donating proceeds of that day’s kefta pita sales to the foundation.

Barbara Stevens prefers to work behind the scenes as president of the foundation’s board.

“She approves everything to make sure that it represents Josh,” Morss said.

Josh’s sister, Shelbie, 19, attending college in Nashville, Tenn., and brother, Sam, 11, also are involved. Recently, Sam was caught being kind at his school.

“Sam has a lot to live up to because his brother has the reputation of being the kindest kid in the world,” Drew said.

Morss said the foundation has started doing corporate programming and is working on putting patches with the “Be Kind” logo on youth sports uniforms.

Josh was known not only as a good athlete but a good sport, the kind of kid who liked to pick those with the least talent when forming a team at the park.

“He liked to look for kids and make them feel important and included,” his father said.

Morss said the foundation tries to represent Josh appropriately in everything, “because we never want to lose him, regardless of how big we get.”

Though Morss never knew Josh, she has come to care deeply about his family. “It’s not just Josh. … He didn’t become kind out of the blue. This family is incredibly magnetic. They are incredibly genuine, and you quickly realize where Josh got his kind heart from.”

Drew Stevens said he wants 1,000 schools to embrace the Josh Stevens Foundation, and he hopes to see it inspire one million acts of kindness.

At the Galloway Elementary School assembly, Drew Stevens asked students to consider Josh’s legacy and to think about their own actions.

“I stand here as living proof that your legacy impacts many,” he said.

Josh wasn’t perfect, he told them, just kind. And that is how he is being remembered. That is his legacy.

As far away as Uganda, Africa, a classroom and playground have been named after Josh, his father told the boys and girls seated before him. “He will forever be known as the incredibly kind kid who started a kindness revolution in the Las Vegas Valley that is now spreading across the globe.”

Contact reporter Carri Geer Thevenot at cgeer@reviewjournal.com or 702-384-8710.