all it the opposite of a rainy-day fund.

Valley water managers opened the community’s first water savings account 20 years ago, literally banking on the day the valley could no longer live on its Colorado River allotment alone.

That day may come sooner than expected. The Southern Nevada Water Authority faces cuts to its annual Colorado River entitlement next year to help slow Lake Mead’s decline. Even before that, the seven Western states that draw water from the river face a March 19 federal deadline to submit plans to voluntarily trim their use on top of the looming mandatory cuts.

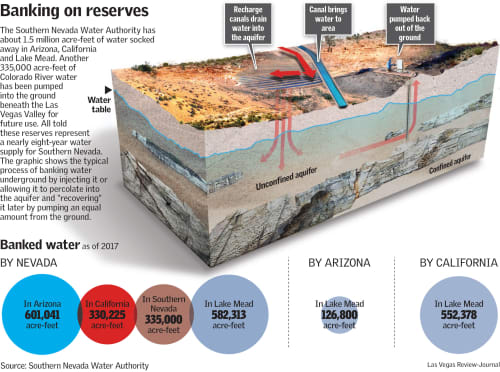

The Southern Nevada Water Authority now has about 1.5 million acre-feet of water socked away in Arizona, California and Lake Mead. Another 335,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water has been pumped into the ground beneath the Las Vegas Valley for future use.

These reserves represent a nearly eight-year water supply for Southern Nevada, though they would never be depleted so quickly. Depending on local conservation and regional drought conditions, water officials expect the community to be able to live off its savings for several decades at least — long enough, they hope, to allow permanent new water resources to be developed and brought online.

A surge in population coupled with unexpectedly deep shortages on the river could force the community to start dipping into its water savings account as soon as 2022, according to the latest 50-year resource plan approved by the authority’s board in November. Or, under the sunniest (and least likely) scenario, the authority could make it through that period without touching its reserves, assuming growth stays at projected levels and conditions on the Colorado improve enough to avoid water shortages altogether.

In either case, that water savings account represents an important safety net for a community that gets 90 percent of its supply from a single, fickle source.

“And where did all that banked water come from? Conservation,” said Doug Bennett, conservation manager for the authority. “People say, ‘Well, what do I get for conserving?’ … (We’re) banking that water for future use by you or whoever may come after you. That’s critically important.”

Accounts in several states

The community built up its savings account relatively quickly by using less than its annual river allotment and squirreling away the rest.

Colby Pellegrino, head of water resources for the authority, said most of the reserves were banked between 2001 and 2010. In recent years, she said, Nevada has largely left its unused water in the river as part of a multistate effort to slow the decline of Lake Mead, which has seen its surface drop 130 feet over two decades of drought in the mountains that feed the Colorado.

California, Arizona and Mexico also have been parking water in the reservoir. Without those contributions, officials say, Lake Mead would be as much as 30 feet lower than it is.

Watch: Banking on the future

The authority’s largest reserve account is in Arizona, where it has paid more than $122 million to bank 601,000 acre-feet since 2001. Arizona took that water off the river and injected some of it into underground aquifers near Phoenix and Tucson for future use.

When the time comes for a withdrawal, the authority will simply pump extra water out of Lake Mead, subtracting it from Arizona’s annual share.

Nevada has a similar arrangement with California, thought it took on new urgency in 2015. That’s when the authority sold about 125,000 acre-feet of water from its reserves in Lake Mead to the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California to help it weather a historic drought in the Sierra Nevada that significantly affected its water supply. In return, the authority received more than $44 million, along with an option to buy the water back and pull it from the lake in the future.

“Who would have thought that we’d go from overusing our allotment during surplus times to loaning water to our neighbors in California because we had conserved so much?” Bennett asked.

Since 2004, the authority has banked more than 330,000 acre-feet with California, including the water it sold to the Golden State in 2015.

In the lake and underground

Nevada has another 531,000 acre-feet stored in Lake Mead, where the authority has earned credits for everything from investing in a water-saving reservoir in California near the Mexican border to buying rights on the Virgin River and allowing the water to flow into the lake.

How much water Nevada can pull from each of its bank accounts in a given year is governed by a tangle of rules, but the authority expects to have access to at least 128,000 acre-feet annually from the reserves.

One account lies beneath our feet.

Las Vegas water officials started injecting excess river water into the local aquifer in the 1980s. Pellegrino said the groundwater bank now holds about 335,000 acre-feet. She expects that reserve account one day to provide about 20,000 acre-feet a year on top of the roughly 45,000 acre-feet local utilities already pump from the ground annually to help meet peak summer demand.

But Southern Nevada’s reserves won’t last forever. So what happens when the community drains its savings account?

By then, local officials hope to be drawing from one or more so-called “future resources,” which include such expensive and so far unproven ideas as large-scale ocean desalination and importing groundwater from arid basins across eastern Nevada.

“This isn’t the totality of all of the future resources. These are the ones we feel the most confident that we can rely upon if we needed them,” Pellegrino said.

Ultimately, the decision about which new water supplies to pursue will come down to reliability and cost. “We know ‘desal’ technology is advancing, and today it might not be the cheapest of the things on this list,” Pellegrino said. “But certainly 10 or 20 years from now … it might be.”

Saving for the future

John Entsminger, general manager of the authority, said recent agreements between the United States and Mexico provide a framework for Nevada to invest in a major desalination plant on the Mexican coast in exchange for some of that country’s 1.5 million acre-feet of Colorado River water. Such a facility could provide drinking water to the cities of Tijuana and Rosarito Beach, allowing them to reduce their dependence on the river and “leave that water in Lake Mead,” he said.

A convenience store in the tiny White Pine County town of Baker sells anti-pipeline bumper stickers in September 2018. (Henry Brean/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Entsminger sees similar opportunities among the seven states that share the Colorado, “as we continue to break down some of the old 20th-century dogma around interstate cooperation.” Cities can help farms pay for efficiency improvements that will allow them to grow more food with less water, freeing up more of the river for municipal use, he said.

In the meantime, the authority continues its controversial, decadeslong campaign to tap groundwater in parts of rural Clark, Lincoln and White Pine counties and pipe it to Las Vegas.

The project, first proposed in 1989, is expected to cost $15 billion or more — assuming the authority ever wins all the approvals it needs to build it.

The agency has already spent more than $100 million on studies and prep work, including almost $79 million to buy ranches and water rights at the business end of the proposed pipeline.

Rural residents, ranchers, American Indian tribes and conservation groups have united against the project, which they say would ravage the target valleys and the livelihoods of those who live in them, while producing too little water to justify the enormous expense.

“The water that SNWA wants doesn’t exist, and they have failed to prove that it does time and time again,” said Kyle Roerink, executive director of the Great Basin Water Network, an advocacy group that has been fighting the pipeline from the tiny White Pine County town of Baker for more than 15 years.

Gov. Steve Sisolak isn’t crazy about the idea, either.

“Any policies we choose to move forward with to solve our water crisis must be statewide solutions, not ideas that benefit one locality over another,” he said in a written response to questions from the Review-Journal. “There are multiple alternatives to the pipeline that we should pursue before we even consider spending that much money on a pipeline, including increased conservation and desalination projects.”

The cheapest option

Former U.S. Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev., offered a very different take in a recent interview with the Review-Journal — one that probably won’t sit well with many rural residents.

“If you go up to Lincoln County, there is greenery on the both sides of the highway: farms growing alfalfa,” the 79-year-old said from his offices at Bellagio. “How many jobs do those farms create? You could put every one of those jobs in this office here.”

Water in an alfalfa field on the Great Basin Ranch in Spring Valley in August 2017. (Review-Journal file)

“That water could be used to flush toilets on the Strip,” Reid said.

Entsminger said he hopes the pipeline to eastern Nevada never has to be built, but he wants it permitted and ready to go, just in case. “When you have limited options, you don’t take options off the table 30 or 40 years before you might need them.”

To him, though, the community’s cheapest and most responsible option is to use less of — and do more with — the water it already has.

“I think our first resource is conservation. Being able to manage our demand is the No. 1 way we’re going to prevent needing to bring new resources on,” he said.

Bennett thinks so, too.

“There’s not a huge desire to go out and implement gigantically expensive resources when we’re still wasting water,” the authority’s conservation manager said. “Certainly you can’t say those (new) resources will never be needed in Southern Nevada, but you want to say that you didn’t reach for them when you didn’t have to.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.

The intake towers at Hoover Dam at Lake Mead National Recreation Area in October 2018. (Richard Brian/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Bank statement

Here’s a breakdown of the temporary resources the Southern Nevada Water Authority has socked away for future use. (One acre-foot is enough water to supply two average Las Vegas Valley homes for just over one year.)

Southern Nevada Water Bank

Account balance: 335,000 acre-feet stored in the ground beneath valley.

Withdrawal limit: 20,000 acre-feet a year, pending state approval.

Arizona Water Bank

Account balance: 601,000 acre-feet, stored in the ground in Arizona

Withdrawal limit: 40,000 acre-feet a year from Lake Mead, unless Arizona cities are taking mandatory cuts under Colorado River shortage.

California Water Bank

Account balance: 330,000 acre-feet, delivered to California with buy-back option.

Withdrawal limit: 30,000 acre-feet a year from Lake Mead under any conditions.

Intentionally Created Surplus

Account balance: 531,000 acre-feet stored in Lake Mead, some of it subject to evaporative losses of 3 percent a year.

Withdrawal limit: 100,000 acre-feet a year from the lake, unless the river is in shortage.