Steve Aoki embodies Las Vegas’ core principle: Always put on a show

There is no rabbit hole to plunge down, just a nondisclosure agreement to sign. Scrawl your name on a digital tablet, promise not to reveal this place’s exact location and, with that, a wonderland awaits.

It’s not one of the Lewis Carroll variety: In place of hookah-huffing caterpillars, this 16,000-square-foot fantasia is populated by G.G. Allin bobblehead dolls — two of them! — Jabba the Hut figurines and a Banksy sculpture of a python devouring Mickey Mouse.

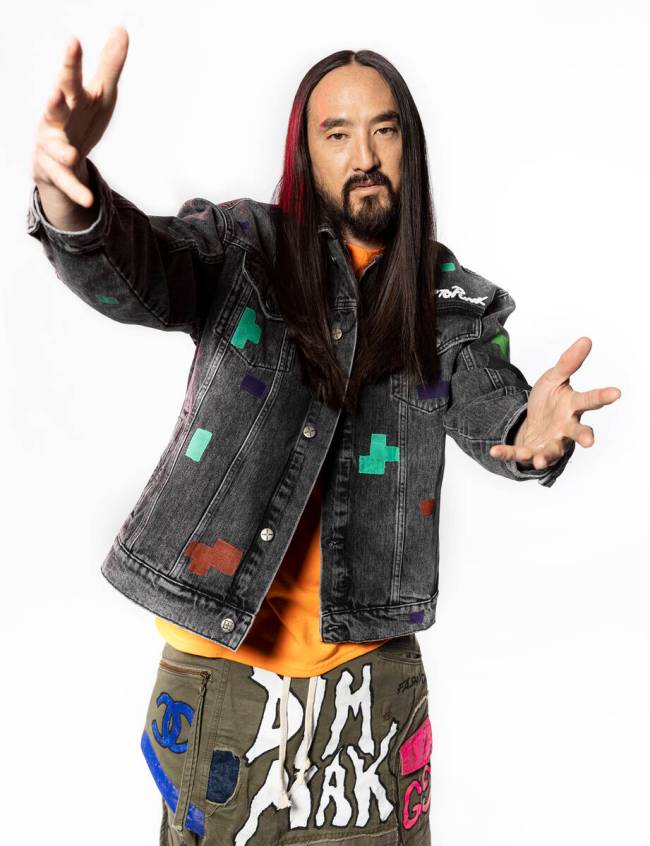

There is a Mad Hatter of sorts here, a long-haired DJ-producer and entrepreneur who may be the only musician to have collaborated with the Backstreet Boys and British anarcho-punks Crass while also overseeing his own fashion line, designing a $3,000 watch with Bulgari and becoming an ambassador to the World Poker Tour.

Turns out he owns the place.

“My house is a collector’s house,” Steve Aoki explains, though he hardly needs to, his words rendered redundant by walls lined with a Footlocker’s worth of sneakers; a room dedicated to the 3D work of graffiti artist Kaws, and enough Bruce Lee memorabilia to open a museum. “Everything in this house has a story,” the 44-year-old Aoki notes on a Thursday afternoon in January, clad in a jean jacket adorned with a logo patch from NFT collection CryptoPunks.

Aoki’s story is just as far-out as the Lego sculpture of himself that keeps watch over the living room. The son of Benihana’s founder Hiroaki “Rocky” Aoki, he has built an empire as a top-drawing DJ-producer and label owner and businessman of many stripes — of course he designed his own Topps baseball card line, co-owns Vegas-based esports organization Rogue and recently opened anime-inspired Japanese restaurant Kuru Kuru Pa with his brother Kevin at Resorts World Las Vegas. A relentless road dog, he plays as many as 300 shows a year, setting a Guinness World Record in 2012 as the world’s most traveled musician after performing in 41 countries.

According to Forbes magazine, he earns more than $20 million annually, and he’s been ensconced near the top 10 of DJ Mag’s influential Top 100 DJs poll for the better part of a decade. “He’s become a global brand,” says Carl Loben, editor in chief of DJ Mag. “It took him quite a bit of hard work to get there in the first place, and it also takes a lot of time and effort and resources to stay somewhere in the upper echelons of the DJ Top 100 chart.”

In Vegas, which has steadily ascended into a destination market for high-end nightclubs and the superstar DJs who perform in them, Aoki has played a leading role in propelling this city into an EDM capital, now performing 40 to 50 shows here annually at his residencies at Hakkasan, Omnia and Wet Republic. “He’s the epitome of a Vegas act,” says James Algate, senior vice president of entertainment and brand strategy for Tao Group, which operates all of the aforementioned venues. “He’s full-on entertainment.”

He’s also a full-on local, having bought his palatial spread in Henderson a decade ago and spent millions remodeling it. (That’s all we can reveal of its location; see the NDA). “It’s incredible to feel like I’m part of the Las Vegas ecosystem,” Aoki says. “I am a Las Vegan,” he notes with a grin. “Is that what you call it?”

How’d he get here? By internalizing the core principle of the city he now calls home: always put on a show.

Oh, and cake. Lots of cake.

Tumbleweeds on the Dance Floor

Before the $150 million nightclubs, before Electric Daisy Carnival began drawing nearly half a million party people, before DJs started having their faces appear on the video marquees of big casinos like the MGM Grand — where Aoki’s visage keeps intermittent watch over Tropicana Avenue — Las Vegas’ dance music scene was nearly as barren as the desert.

When Aoki came to Vegas for his first local gig in 2006, for which he was paid a cool $1,000, there were only a few clubs in Strip casinos — Ra at Luxor, Studio 54 at the MGM Grand, Pure at Caesars Palace — and the big-name DJs tended to avoid them for fear of being reduced to playing Britney Spears remixes for indifferent tourists.

“There was never really a dance scene there. I was so shocked about that,” superstar DJ-producer Tiesto recalled in October. “Even when I did my residency at the Hard Rock (which began in 2011), it was amazing, but it was not easy to fill that place, to try to find 5,000 people in Vegas who like dance music.” It was definitely a journey.

“Nobody knew back then, that’s for sure,” he adds of Vegas’ rise to nightlife pre-eminence. “Some weekends you literally have, like, five top headliners playing different clubs in Vegas — and everything is packed. It’s amazing, because it wasn’t like that back in the day. You had one club, maybe two and that’s it — and they weren’t even full.”

What’s more, the clubs were the primary attraction in those days, not the DJs. “The DJ in Vegas was, like, hidden,” Aoki recalls. “I’d play these very small rooms, these side rooms. It was like, you’re in the corner and you’re just playing music.” I remember going to see (DJ) AM, DJ Vice, these other bigger names at the time in Vegas, and you don’t even know where they are. You can hear their music and their mixes, ‘Oh, (expletive), that’s AM. I have no idea where he is, though.’”

A major turning point came in 2008, when Paul Oakenfold — arguably the first superstar DJ — inked a one-year residency at Rain at the Palms. Two years later, Aoki and fellow star DJ Kaskade were among the first acts to sign on for residencies at Wynn Las Vegas when Surrender and Encore Beach Club opened and Vegas’ club boom began in earnest. “I got paid 10 grand,” Aoki says. “That was a lot of money in 2010. A lot of money. The shows, they were good, but it was still brewing.” Hakkasan, new to the market, came calling in 2014.

“With Steve, we definitely saw something,” Algate says. “He was an artist who was on the rise, was probably not getting his dues where he was performing before. His performance really captures everything you want from a headliner in Vegas. Not only do people come in and fly from all over the world to see him, when he gets them in the room, nobody leaves.”

Basement Beginnings

Aoki gazes up at the ceiling. It gazes back at him, in a way, the swirls of color a reflection of the man sitting beneath them. “I wanted this room to have this kind of feeling of paint falling on top of you,” he explains while reclined on a couch in his library. “This is like an art room, like a living art piece — an experiential art piece. I wanted to feel like we’re kind of, like, in another world.”

We kind of are. To Aoki’s left: a large collection of vinyl records, ranging from The Beatles to Marvin Gaye to Paula Abdul; all around us, hundreds of books, encompassing everything from the forensics of airline crashes (“Beyond the Black Box”) to the science of war (“Grunt”) to artificial intelligence as it relates to the future of humanity (“The Singularity”) to, of course, a quartet of books by Bruce Lee.

On one hand, Aoki is an extremely meticulous man: He oversaw the design of this room, of his home, right down to the depth of the pools outside (“Everything in this house is purposeful; I like to have purpose with everything I do”). He’s relentlessly big on the little things. On the other, he’s an impulsive thrill-seeker prone to learning on the fly, running before he can walk.

Perhaps it’s in his blood.

There’s a scene in Aoki’s 2016 Netflix documentary, “I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead,” in which he describes his father’s zeal for risk-taking, both in business and in pleasure. “He didn’t know what he was doing; he just did it.”

That’s how Aoki’s career in music began: At 15, he picked up a guitar. He didn’t know what he was doing. He just did it, learning how to play in six months. He also learned how to do the same on bass and drums and recorded his first demo, on which he played all the instruments and sang.

He started a band shortly thereafter, cutting his teeth in the hardcore punk scene of his native California, self-releasing numerous albums. At the University of California, Santa Barbara, he threw shows in the student housing co-op and started his own record label, Dim Mak, named after Bruce Lee’s death punch. Everything was DIY — everything had to be. There were no other options.

By the time he was 21, he’d completed 14 U.S. tours, a precursor to the rigorous roadwork he still engages in, traveling in a van, crashing on strangers’ couches, in basements, wherever. He recalls a time when one of his bands drove 10 hours to play a gig in Albuquerque, NewMexico, for $18 — split four ways — in front of fewer than 10 fans.

He was less disappointed, he says, than stoked that that many people cared to begin with.

“I go into the room not saying, ‘Oh, (expletive), there’s only eight people,’ ” Aoki recalls. “I go into the room saying, ‘There’s (expletive) eight people here. We’re going to have a great time,’ because I don’t really care about anybody else who’s not in the room. Those eight people are there, so let’s make the most of it.”

Decades later, those shows still inform his approach. “I just need one person to really care,” he says. “If I can find that one person, I’m good.”

We’ve Got to Talk About the Cakes

If there’s one lesson Aoki took from his early gigs in Vegas, it was one of the most important — and intuitive — ones, one that’s come to define his career ever since: If you want to make it as an entertainer, be entertaining.

“Vegas is a place where I really had to learn how to entertain an audience,” Aoki explains. “When you play a concert to your fans, you could just stand there and play, and they’re all going to go crazy because they love your music already.

“In Vegas, it’s the opposite. They know your name. They might know a song, maybe. But they need to be entertained. They’re coming to be entertained. And if you don’t bring the goods, that’ll matter. So, I learned to entertain here.”

There was also an epiphany Aoki had while performing at Coachella for the first time in 2007, when he saw robot-helmeted French electronic duo Daft Punk perform — and steal the festival with a stage design that included a massive pyramid of lights. “I’m like, ‘That’s a show. That’s a stage production,’ ” he recalls. “I heard what happened: They got 300 grand to play and they spent the whole 300 grand building out that stage. And I’m like, ‘These people care more about the show than the money. This is exactly what needs to happen.’ ”

Two years later, Aoki was invited back. He was paid $4,000 to perform. He spent $7,000 building his production, which featured illuminated cubes spelling out his last name, dancers in brightly colored, custom-designed cloaks and a simple yet ingenious prop that would become one of his trademarks: inflatable life rafts that he’d toss into the audience and crowd-surf in.

“Boom! I got into Rolling Stone because of that, because I was in a raft in the crowd,” Aoki says, his pride undiminished 13 years later. “At the same time, I was talking to Kanye West. I was working on music with him, and he mentioned that to me, ‘Yo, man, I saw you in the raft. That was crazy.’ I was like, ‘Wow, people remember that more than me actually DJing.’ That was a moment that people never forgot.”

Neither would Aoki: More than any other DJ, he focused on putting on a show. Goodbye to the days when the DJ simply pogoed behind a laptop with his arms in the air. Hello, baked goods.

In 2011, Aoki got the idea of going to a bakery, designing a cake, then filming himself tossing it into the face of a willing fan at one of his shows.

“We put it on YouTube. It blows up, goes viral,” he recalls. “I started doing it every show. I had the raft out. I mean, my show was by far the most engaging, entertaining show in the DJ space.”

The caking became a calling card — for better or worse. “People who go to see one of his shows now expect there to be some cake throwing,” Algate says. “He did try and stop doing it at one point, and people were like, ‘Hey, where’s the cake, dude?’ It’s kind of his trademark, I suppose.”

Of course, the backlash was inevitable: He’s elevating style over substance! Dessert hurling over art! “‘He doesn’t even DJ; he’s just caking people,’ ” Aoki chimes in, parroting his critics. “They don’t even come to a show. They just see a video of me caking someone. Of course I’m not DJing at that moment.

“The actual act of DJing, a 6-year-old child can do it,” he continues. “It’s not difficult. It’s like with any instrument. Anybody can pick up a guitar — anybody — and you give them four months or six months or whatever, and they could probably play one of their favorite songs very generally. Anyone can DJ. If that’s your insult, that’s pretty weak.”

OK, so what makes Aoki special?

He points to his ear.

“I feel like I know where the best attributes of my talents are, which is right here,” he says. “I know I can find and source bands that will break. I also realized that I had a good ear on what the melodies are, what the sound is, what’s really going to hit in the culture.” Some of the acts that Aoki has helped break, either by signing them to his label or collaborating with them early in their careers: Bloc Party, The Kills, MSTRKRFT, The Bloody Beetroots, The Chainsmokers.

Catching Dreams, Banking Millions

It looks kind of like a psychedelic Ewok, or maybe a stoner werewolf that prefers hacky sack to howling at moons. It made Aoki $888,888.88. The item in question: “Hairy,” an NFT Aoki created with visual artist Antonio Tudisco. It was part of the 11-piece “Dream Catcher” collection the two auctioned off in March, netting them $4.25 million. “Hairy,” based on Aoki’s artist logo, was bought by former T-Mobile CEO John Legere, who’s also spent big money on an NFT from fellow Vegas DJ 3lau.

“It took six months to develop,” Aoki says. “Since then, I’m going all-in. I really believe in the space.”

In January, Aoki stopped one of his live shows to announce that he had purchased a rare alien NFT from digital artist Doodles, which cost a reported $859,000. “NFTs make me feel like a kid again,” he said in a tweet afterward.

When the pandemic hit, Aoki got seriously into card collecting: In November, he auctioned nearly $3 million in Pokemon cards and merchandise. But he’s especially evangelical about NFTs and, by extension, the metaverse and web 3.0, a new, blockchain-based version of the internet. In January, he announced the launch of Aok1verse, an NFT-based, “tokenized social club” that offers token holders digital and traditional access to Aoki and his collaborators.

“This is the biggest project of my life,” he says. “It’s going to be a game-changing new concept, something that’s going to include my entire world, everything.

The way Aoki sees it, not only will one’s online identity in the metaverse one day become indivisible from their real-life self — in some instances it might actually take precedence.

“As we go dive deeper into the metaverse, it’s going to be a large component of how we live our lives, how we represent, what matters to us. Like, someone might spend $200,000 on a Richard Mille watch; they might be more inclined to spend $200,000 on an NFT of a Richard Mille watch that they put on their character in the metaverse.

“It’s things that you associate with. The same reason why people buy a Louis Vuitton sneaker or a woman buys a Chanel purse: She loves the association, and it identifies with her character. This brand is imprinted with her. She’s spending $4,000 carrying that, the same way someone’s spending $4000 on an NFT saying, ‘This identifies as me.’ Identity is such a big part of how we spend our money, and soon, the way we identify will be so much more in the metaverse than it is in IRL.”

Aoki’s passion for NFT feels like a natural extension of his punk rock roots. Like starting your own label, NFTs began on a DIY level and represent an egalitarian art form with few barriers to entry. Just like it doesn’t take a ton of musical know-how to crank out a three-chord punk song, NFTs can be made by virtually anyone — the hard part, of course, is finding an audience.

Finding new audiences, though, is kind of Aoki’s thing.

“I think one of my favorite things in life is the ability to create something that you’re a part of that you love, a culture, a community, expand it, and watch other people become a part of the formation of something exciting,” he says. “That’s why I love NFTs, this metaverse, web 3.0, because we’re doing exactly that, right now, building into this wild, wild West of the unknown — truly the unknown.

“Will it happen?” he asks “No one knows, but I’m betting on it. I’m investing into it, financially, spiritually, mentally, physically, my labor, my time, my effort, just everything.”

In the meantime, here, outside the metaverse, there are shows to play.

“The whole world knows what Las Vegas is. The whole world wants to come here. I feel really special to be a part of that,” he says. “Having the world come to me, it’s like, I have a responsibility, plain and simple. I need to keep them coming.”

Spoken like a true showman.