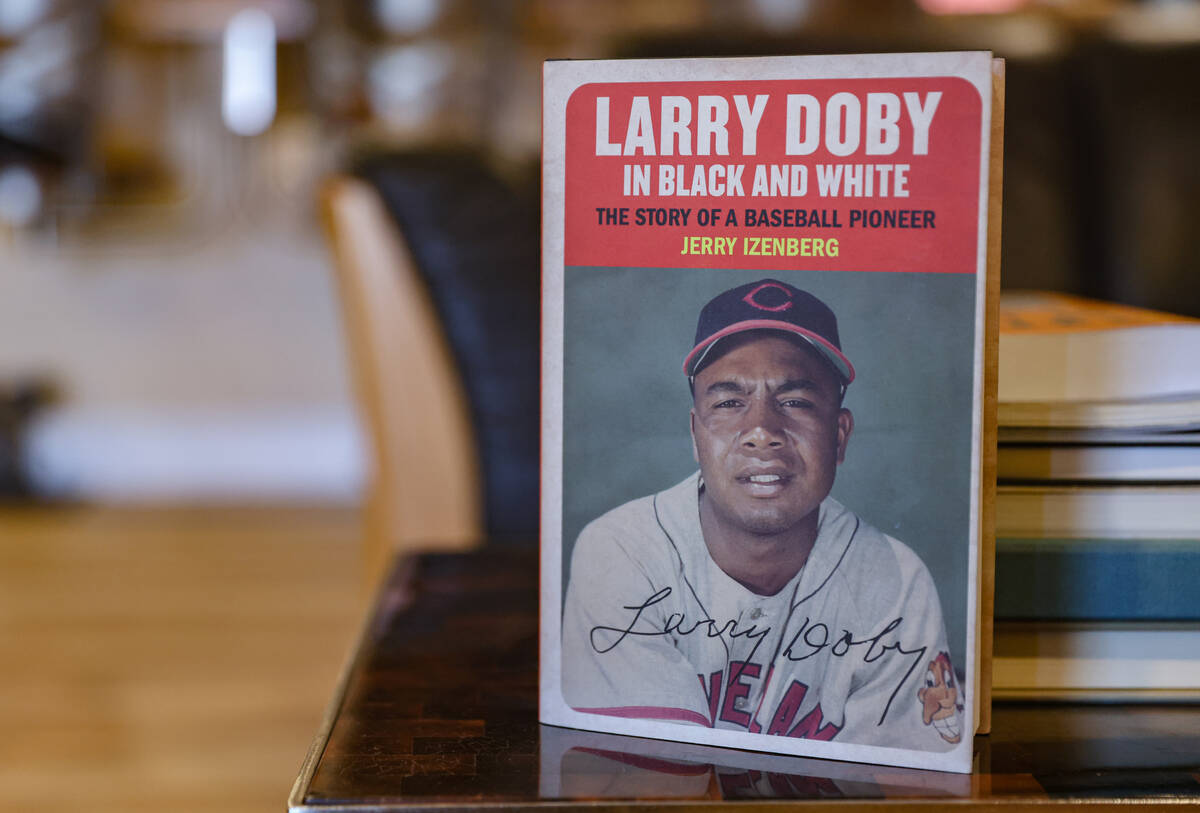

‘Cleveland Ain’t Brooklyn’: Henderson sports writer pens book at 93 on MLB pioneer

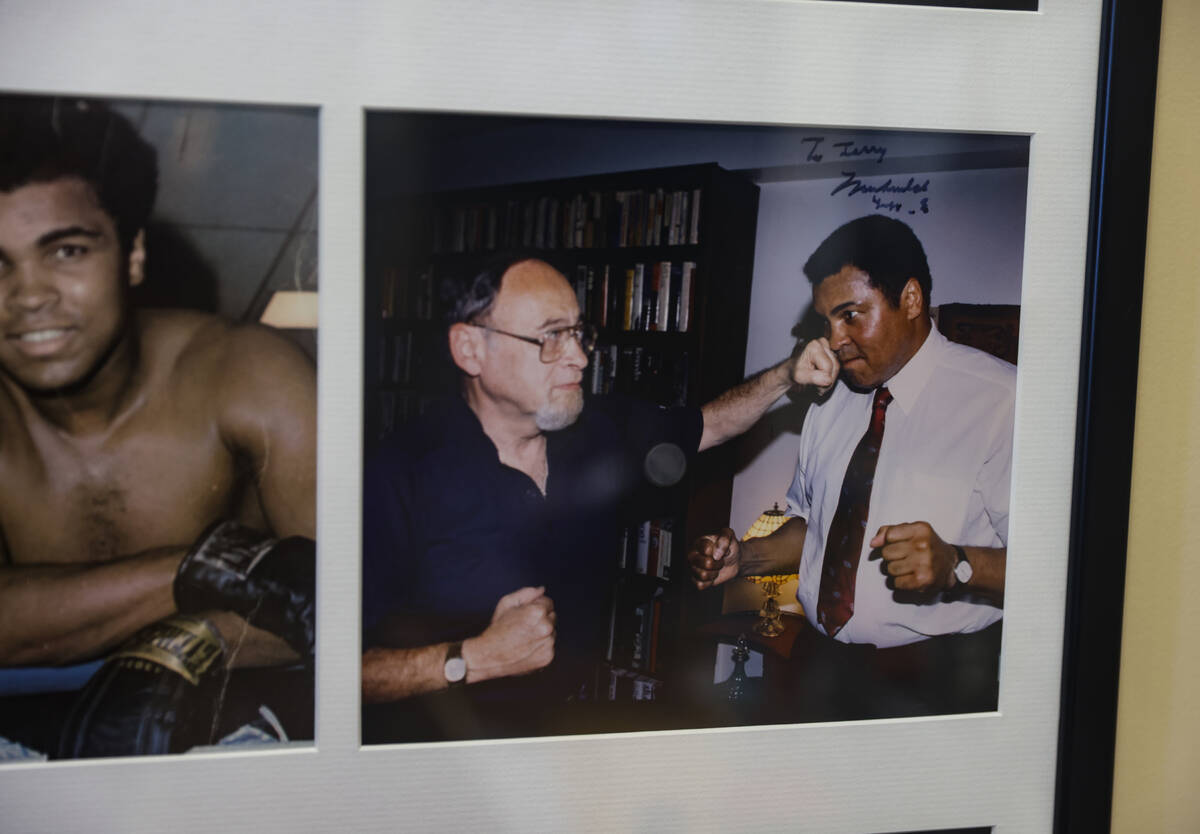

Hall of Fame sports writer Jerry Izenberg helped Larry Doby get elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, with one notable assist.

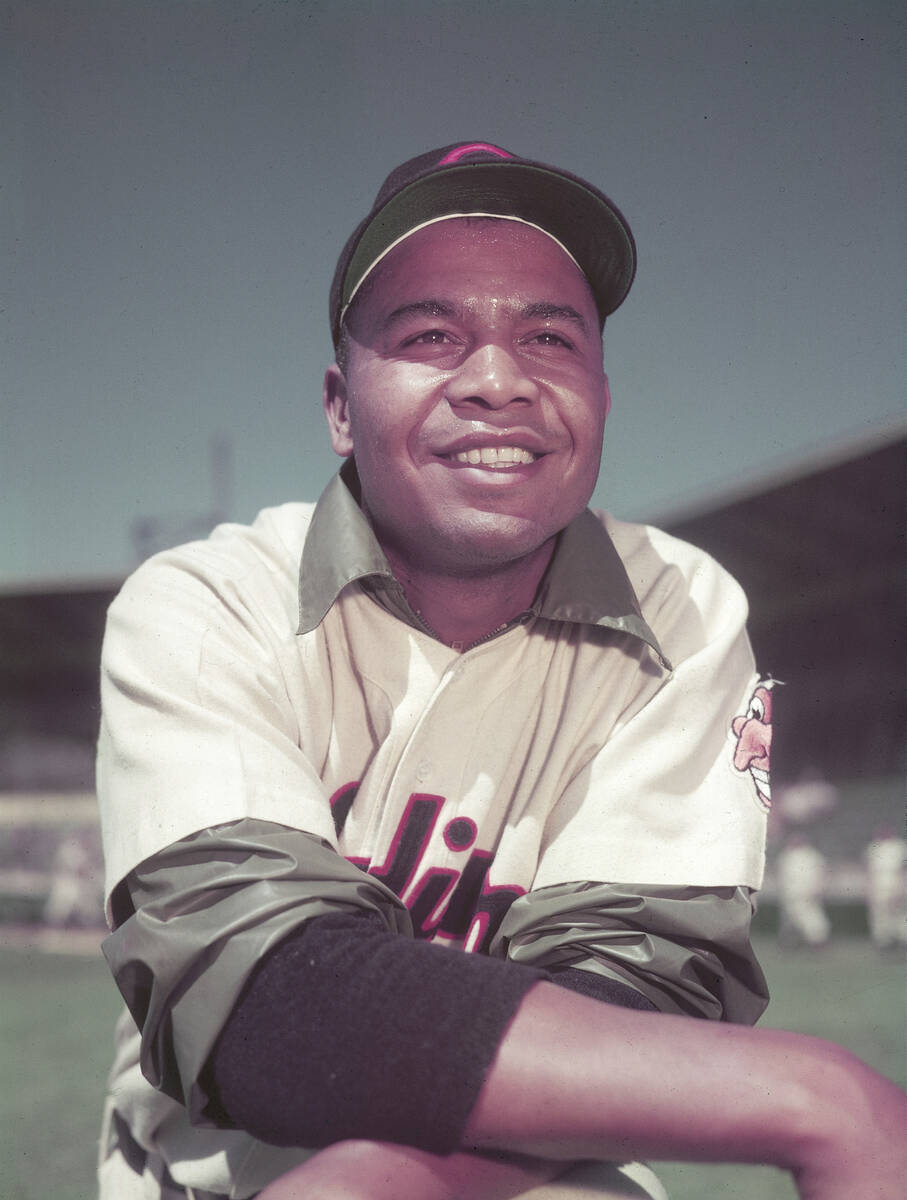

Doby asked Izenberg, his close friend, to stop pleading his case more than 50 years after he broke the American League color barrier with the Cleveland Indians on July 5, 1947. That historic moment took place less than three months after Jackie Robinson became the first Black man to play in Major League Baseball on April 15, 1947, in the National League for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

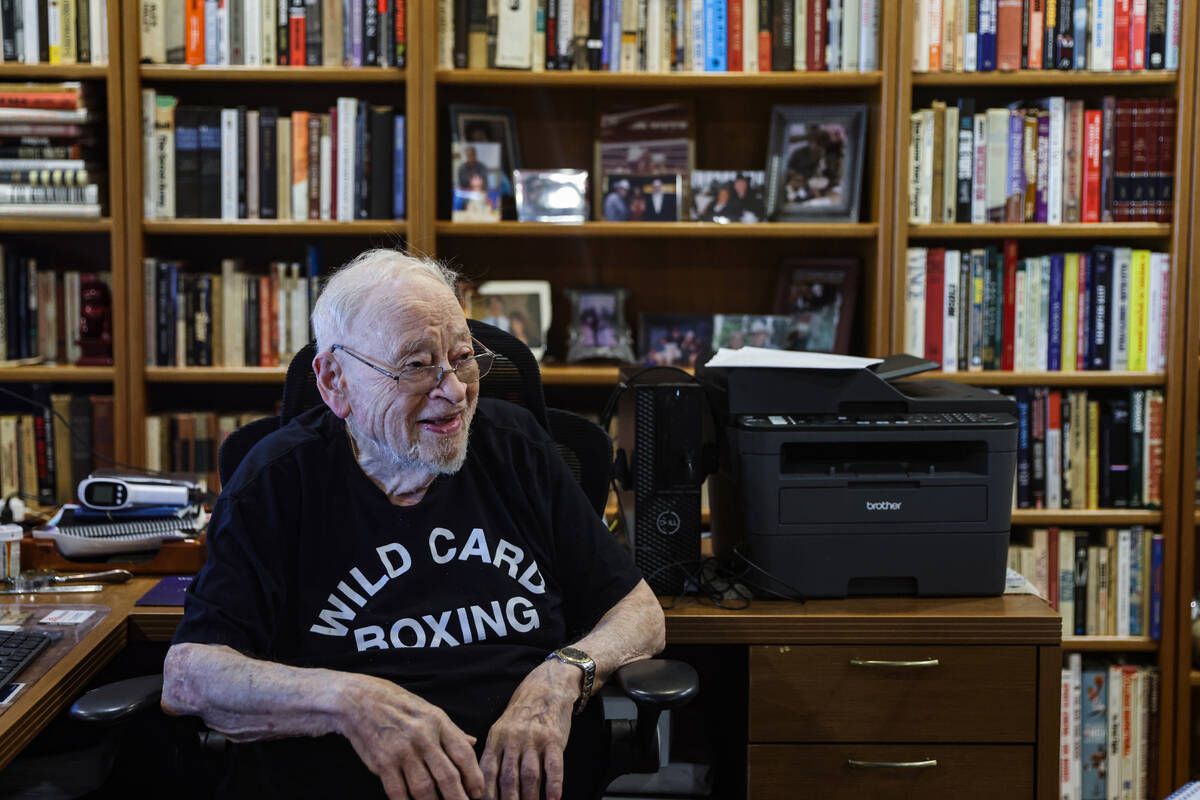

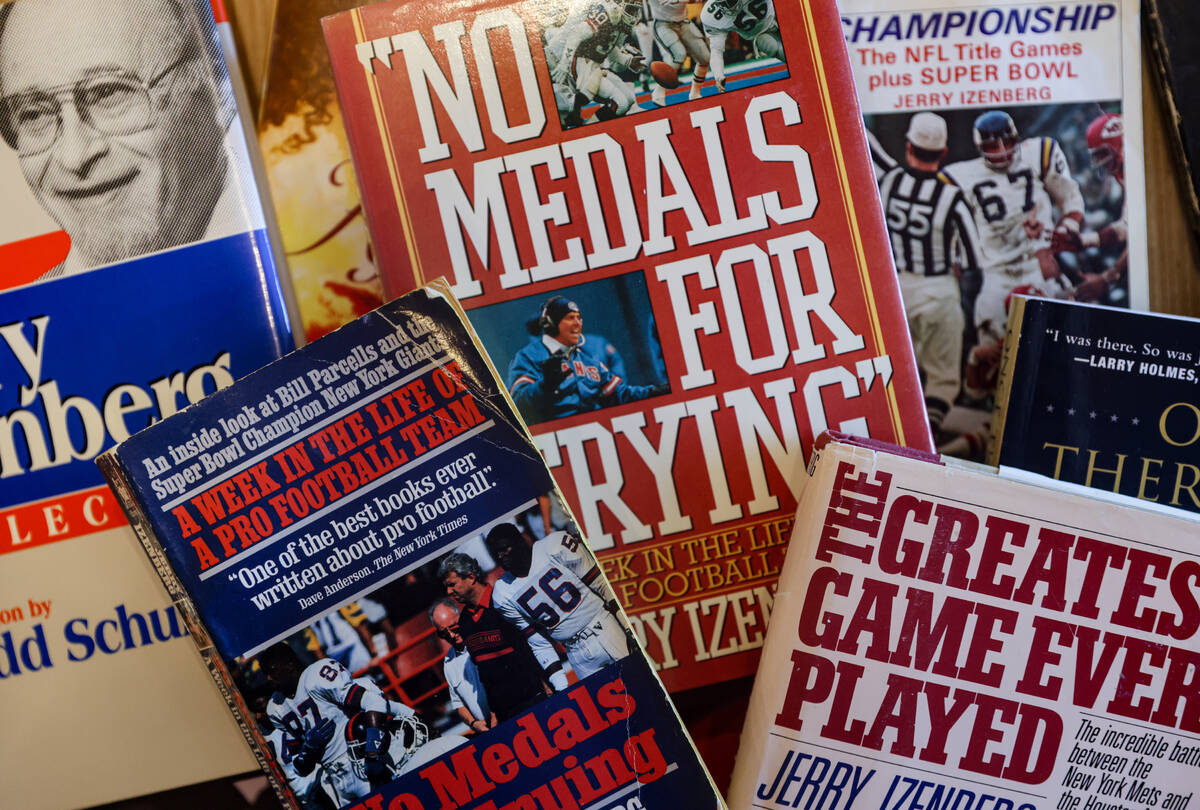

But Izenberg, a Henderson resident who at age 93 recently authored his 15th book, “Larry Doby in Black and White: The Story of a Baseball Pioneer,” would not relent. He called out the veterans committee in a column in the Newark Star-Ledger — for which Izenberg still contributes as a columnist emeritus in his 74th year in the newspaper business — for its refusal to put Doby in the Hall.

“Jackie got in the Hall of Fame the first year he was eligible (in 1962). Doby was (74) years old when he got in the Hall of Fame,” Izenberg said Tuesday. “I write one of the nastiest columns I’ve ever written. … I photocopy the column. I send a copy to every member of the veterans committee.

“I get one letter: ‘Dear a———, Monte Irvin, Yogi Berra and I have been trying to get Larry into the Hall of Fame since he came to the veterans committee. Get your fat a— off the couch and go get us some votes we need. Signed, Ted Williams.’”

Doby was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1998. He died in 2003 at age 79, and Izenberg delivered the eulogy at his funeral.

“I got up and said, ‘I came from a prototype of the American family. Mother, father, son, daughter. All my life I wanted a brother. And I lost one today,’” Izenberg said.

Izenberg, born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1930, used to skip school to sit in the stands of Ruppert Stadium and watch the Newark Eagles play in the Negro Leagues. Irvin (shortstop) and Doby (second baseman) were the double-play combo.

A friendship was forged after Doby knocked on Izenberg’s door one night in 1976 and the two Montclair, New Jersey, residents swapped stories over a bottle of scotch until the sun came up.

‘Had it harder than Jackie’

Doby and Robinson faced similar obstacles, including death threats, discrimination and racist taunts, and neither considered quitting. But Doby’s legacy as the second Black man to play in the major leagues has largely been forgotten in favor of Robinson, who has been widely celebrated for being the first and whose number 42 has been retired by MLB.

“I wrote the Doby book because I didn’t want the story of Larry’s lonely battle to be allowed to slip through the cracks, where it could head toward oblivion,” Izenberg said. “He had it harder than Jackie. Which is not to denigrate Jackie.

“The title of the first chapter is ‘Cleveland Ain’t Brooklyn.’ That’s the difference.”

While Robinson spent a year in the minor leagues in 1946 playing for Montreal to prepare for his historic MLB debut, Doby jumped straight from the Negro Leagues to the majors in the middle of the season.

Cleveland was a segregated city with separate schools, separate hospitals and a popular amusement park that Black people weren’t allowed to visit. Doby received a rude reception when Indians player-manager Lou Boudreau introduced him to the team.

“I stuck out my hand. Very few hands came back in return,” Doby told Izenberg. “Most of the ones that did were cold-fish handshakes, along with a look that said, ‘You don’t belong here.’”

Two teammates literally turned their backs on Doby, though five greeted him with firm handshakes and became his lifelong friends.

Doby’s teammates didn’t have his back during a 1947 game in which an opponent spit tobacco juice in his face after he slid into second base.

The lack of support was in stark contrast to what Robinson received that same season from teammate Eddie Stanky during a game in which Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman shouted racial epithets at the Dodgers rookie.

“Eddie Stanky ran across the field and tried to punch Chapman in the mouth,” Izenberg said. “But nobody got off the bench when Larry got the juice spit at him.”

Doby, who unlike Robinson didn’t have a Black teammate until Cleveland signed Satchel Paige in July 1948, had bottles of beer hurled at him during games, as well as verbal and written attacks on his wife and daughter and more.

“Jackie got all the credit for putting up with the racists’ crap and abuse. He was the first. But the crap I took was just as bad,” Doby told Izenberg. “Nobody said, ‘We’re going to be nice to the second Negro.’”

World Series embrace

After batting .156 in 32 at-bats in 1947, Doby hit .301 with nine triples and 14 home runs in 1948, when he helped Cleveland to its most recent World Series championship.

He led the team in the World Series with a .318 average. He became the first Black player to homer in the World Series, and he and Paige became the first two Black men to win a World Series title.

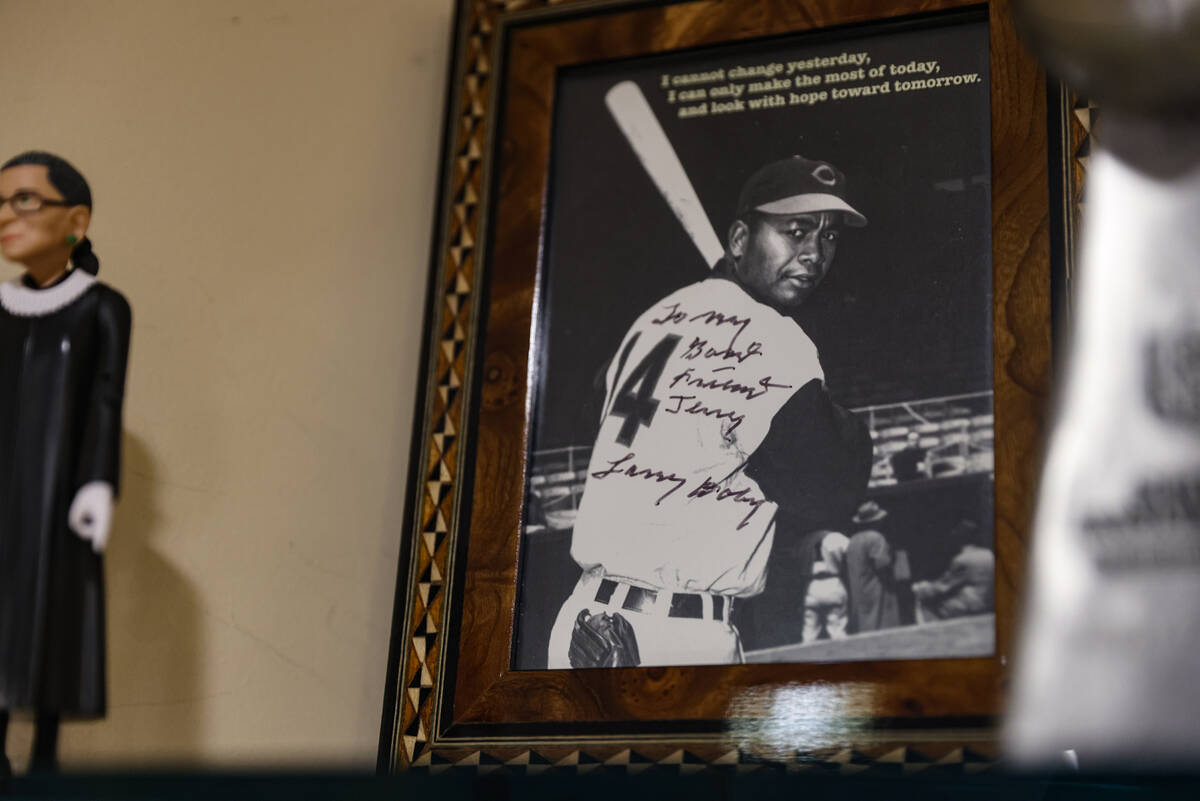

Doby also was part of what Izenberg described as “one of the most significant photographs of the civil rights era.”

The photo was taken in the clubhouse after Doby’s solo home run lifted the Indians to a 2-1 win in Game 4 and a 3-1 series lead over the Boston Braves. It showed him and Steve Gromek, his white teammate and the winning pitcher, cheek to cheek in a joyful embrace, ecstatic smiles on their faces. The image appeared in newspapers across the country, and it was seen as a message of acceptance.

“That was a feeling from within, the human side of two people. One Black. One white. That made up for everything I went through,” Doby told Izenberg. “I would always relate back to that whenever I was insulted or rejected from hotels. I would always think about that picture. It would take away all the negatives.”

Last year, when Doby was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award given in the U.S., on his 100th birthday, the photo was on the back.

Underneath the picture is a quote often told by Doby to his kids: “We are stronger together, as a team, as a nation, as a world.”

Doby also broke the color line in pro basketball as the first Black player in the American Basketball League, the precursor to the NBA. He also was the second Black manager in MLB, following Frank Robinson.

A two-time AL home run king, Doby placed second in MVP voting to Berra in 1954, when he led the league in homers (32) and RBIs (126) and helped Cleveland win the AL pennant.

Izenberg, one of only two sports writers to cover the first 53 Super Bowls, called out the AL to honor Doby.

“The Indians did. They retired his number 14, they named a street after him, and they’ve got a statue of him,” he said. “But where’s the American League?”

Contact reporter Todd Dewey at tdewey@reviewjournal.com. Follow @tdewey33 on X.