Gambling addiction may follow national wave of sports betting

Advocates for responsible gaming are worried that addictive gambling behavior could balloon with the arrival of nationwide sports wagering.

And the state lawmakers who could make a difference by requiring the implementation of new programs aren’t doing much to help.

“With the exception of New Jersey, none of the states that have either drafted bills or moved forward, including Delaware, have come close to adopting even one of our recommendations,” said Keith Whyte, executive director of the National Council on Problem Gambling, based in Washington.

“The states are scared,” Whyte said. “They’re scared of the level of existing problems, which probably is significant, and they’re scared even more so that their golden goose, their painless tax, actually does have a down side.”

The tax is considered “painless” because it’s a charge on a voluntary activity. Tax rates in proposed sports betting bills range from 6.25 percent in Missouri to 61 percent in Rhode Island.

Delaware became the first state outside Nevada to take a legal single-game sports wager on Tuesday when Gov. John Carney put $10 on the Philadelphia Phillies to beat the Chicago Cubs at Dover Downs. He won the bet.

More legalization is on the horizon with 19 states progressing on some form of legal sports betting.

Whyte isn’t the only responsible gaming expert concerned about the prospect of an increase in compulsive gambling because of one of the largest industry expansions in history.

James Whelan, a clinical health professor and the director of the Psychological Services Center at the University of Memphis, has lobbied Tennessee legislators to provide some form of protection for the estimated 2 percent of gamblers — about 5 million people — thougth to exhibit addictive behavior.

Whelan said he was astonished by how little lawmakers knew about the issue and how indifferent they were toward doing anything.

“Legislators don’t get it,” Whelan said. “When Tennessee was passing the lottery bill called the ‘lottery education bill’ because the money goes to education, I went to Nashville probably 25 times to talk to legislators about problem gambling,” he said. “I was blown away” by how little they talked among themselves about the issue.

“I’d say, ‘You know, you really need to think through how you educate all your stores about underage gambling.’ And the legislator said to me, ‘They’re not going to be able to buy lottery tickets when they’re under the age of 18.’ And I said, ‘Oh, OK, so when they come in and illegally buy their cigarettes and alcohol, a clerk’s going to stop them when they ask for a lottery ticket?’”

‘Not really gambling’

Some lawmakers were indifferent, Whelan said, because they didn’t feel the lottery was really gambling.

“I had a legislator come back to Memphis several times because he would not believe that anyone could have a gambling problem because of lottery,” Whelan said. “He would tell me, ‘Well, lottery is not like gambling. It’s not like being in a casino.’”

Whelan fears the same attitude could prevail with sports wagering because, like poker, there is some skill required to participate and sports bettors get overconfident about their abilities.

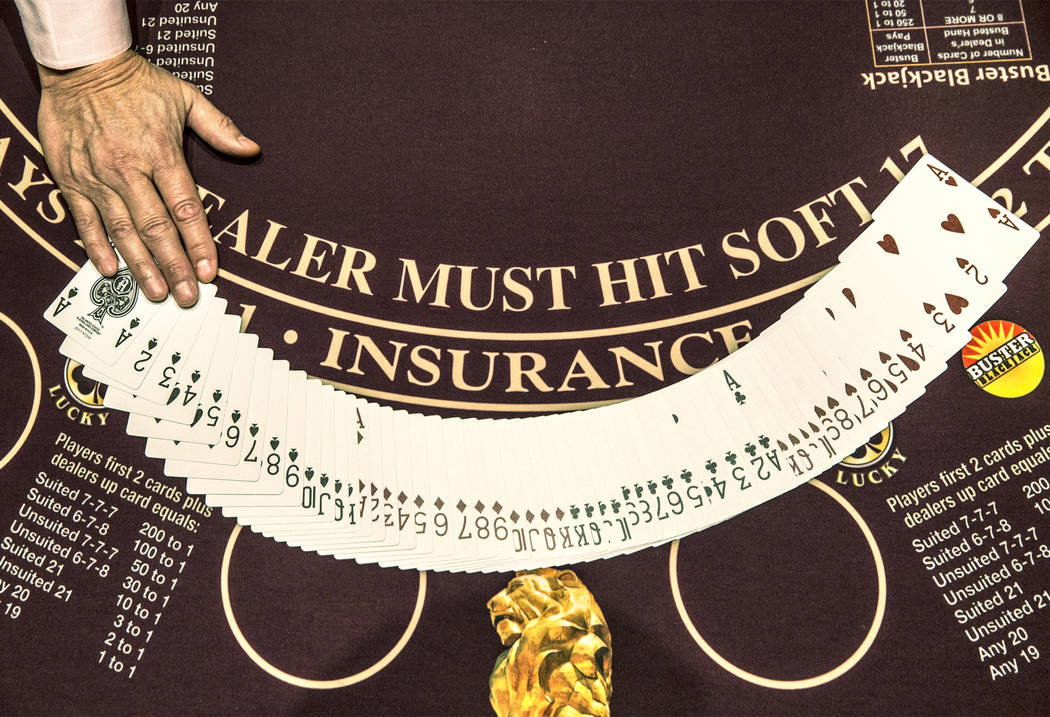

“People in a sports book believe they have skills and knowledge to beat the house,” Whelan said. “When people are sitting at a slot machine, they believe they’re going to get lucky. Even at the blackjack table, people believe they’re making smart bets, but they also know they’ve got to get on a hot streak. They know there’s an element of chance in it. But when you talk to poker players and sports gamblers, they think they’ve got it and that they have special skills and knowledge.”

Whyte said there is some comfort in knowing that established companies that have responsible gaming programs in place will be establishing new sports books nationwide.

“When casinos do things such as allow people to exclude themselves from casinos, like MGM (Resorts International) and Caesars (Entertainment Corp.) embrace responsible gaming practices, there are ways of getting information to people who do harm and limiting in some ways the potential to destroy themselves,” Whyte said. “I always think of it as creating a safety net.”

Alan Feldman, an executive vice president with MGM and an advocate for responsible gaming programs, said it’s important to pay for research for problem gambling to get an idea of whether there’s a problem and if the expansion of sports betting is making it worse or has no impact.

“There is no certainty about the impact on problem gambling,” he said. “Some research indicates that any expansion of gaming increases, for a limited time, the incidence of problem gambling. But in this case, sports gambling is ubiquitous. The increase may, in fact, only be incremental.”

MGM pays for studies

MGM is one of the industry leaders in paying for problem gambling research. A responsible-gaming program called GameSense was mandated by the state of Massachusetts for companies opening casinos there, but MGM opted to install GameSense in all its resorts nationwide. With operating the program, the company is donating $1 million a year for five years to UNLV for problem gambling research.

Whyte viewed the prospect of a major expansion in sports betting as an opportunity, but the response to his calls to action have been disappointing.

“It’s an indictment of how short-sighted the industry can be that they are relying on a small nonprofit in D.C. to cover their ass in all 50 states,” he said.

Contact Richard N. Velotta at rvelotta@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3893. Follow @RickVelotta on Twitter.

Responsible gaming principles

In March, the National Council on Problem Gambling issued five principles recommending what legislators and regulators should do to prepare for the arrival of nationwide sports wagering. Its recommendations on what legislators and regulators should do:

— Ensure that any expansion of sports gambling includes dedicated funds to prevent and treat gambling addiction.

— Require sports betting operators to implement responsible gaming programs which include comprehensive employee training, self-exclusion, ability to set limits on time and money spent betting, specific requirements for the inclusion of help-prevention messages in external marketing.

— Assign a regulatory agency to enforce the regulations and requirements that are enacted.

— Conduct surveys of the prevalence of gambling addiction prior to expansion and at regular periods thereafter in order to monitor impacts of legalized sports betting and have data that will support evidence-based mitigation efforts.

— Establish a consistent minimum age for sports gambling and related fantasy games.

Problem gambling survey

In 2016, the National Council on Problem Gambling surveyed problem gambling services in the United States. Some of the findings:

— While Nevada ranks second in the nation for gambling revenue per adult resident, the survey shows the state ranked 13th for per-capita problem gambling service funding.

— Ten states have no public funding for problem gambling programs.

— In 2016, total spending increased 20 percent to $73 million.

— Nationally, just 23 cents per capita is spent by states on problem gambling.