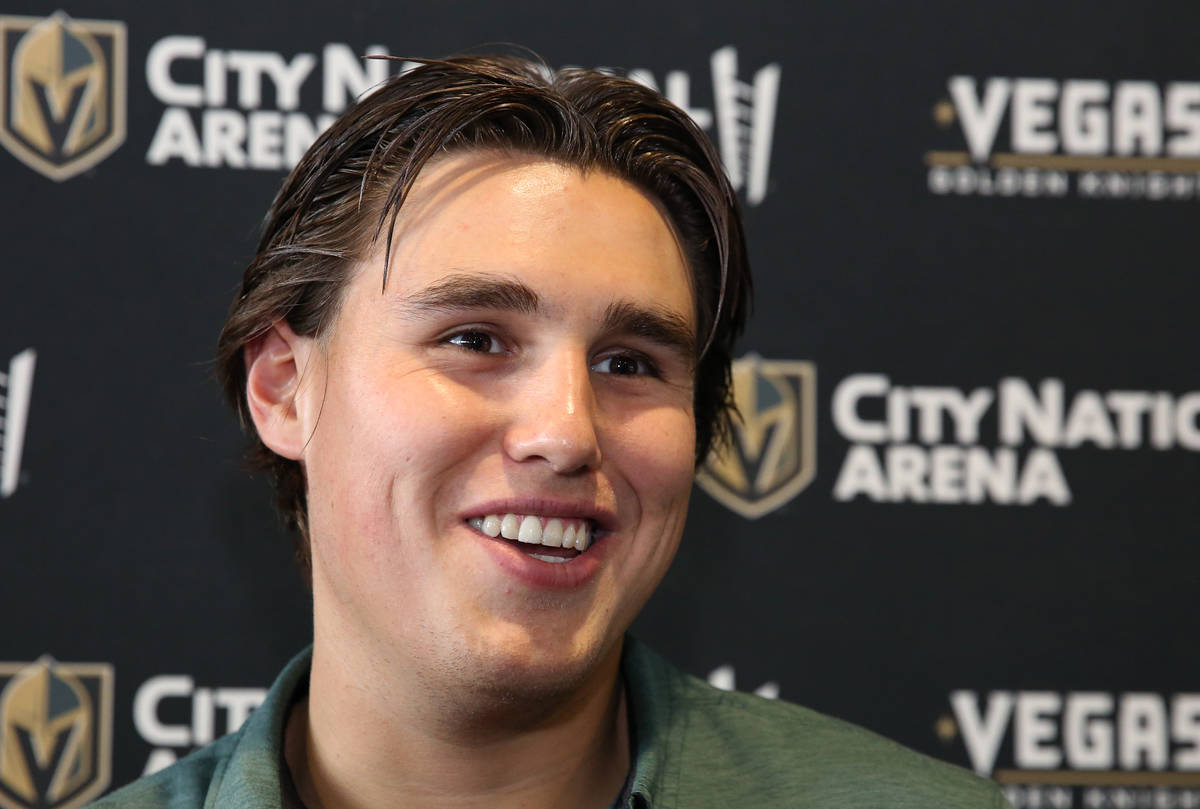

Golden Knights’ Zach Whitecloud carries community on shoulders

Zach Whitecloud made one of the most important decisions of his life in a bathroom.

In March 2018, the then-college free agent had suitors across the NHL trying to pry him from Bemidji State University. So the sophomore defenseman hunkered with agent Dean Grillo for a week to find his best match.

Finally, after taking what he says was his “sweet time,” Whitecloud narrowed his list. When the final choice neared, he sequestered himself in a bathroom searching for a sign. He stared into the mirror for almost a half-hour, saw a Golden Knights jersey, opened the door and told Grillo one word: Vegas.

The story has written itself from there. Whitecloud signed with the Knights, made his NHL debut April 5, 2018, and two years later became a late-season lineup fixture. His steady play in 16 games earned him a two-year extension in March.

The deal was trivial and remarkable at the same time. There was no reason the Knights wouldn’t extend such a promising rookie at $725,000 per season. Yet the word “promising” hasn’t followed Whitecloud’s hockey career around much.

He was never supposed to make it this far. But it’s important to a lot of people that he did.

“In college, I didn’t expect to play pro hockey,” said Whitecloud, 23. “In junior, I didn’t expect to play college. In Triple A midget hockey, I didn’t expect to play junior. Every level that I kept jumping, I think it enabled me to play with a sense of freedom because I was never supposed to make it to the next level. In a sense, it instilled a mindset in me of ‘Play because you love it. If it doesn’t work out, then that’s fine. You did what you wanted to do. You kept playing hockey just because you loved it.’

“Obviously, it brought me here today.”

Origins

Whitecloud grew up in Brandon, Manitoba, but “home” was 30 miles west.

That’s what he calls the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, a reservation of 1,028, according to the 2016 Canadian census. Whitecloud’s father, Tim, is 100 percent indigenous. His ancestors came to the area from southern Minnesota.

Zach Whitecloud visited Sioux Valley often as a child and remains tied to the community. He was raised to respect his people’s culture and traditions, and carry that legacy forward.

“That’s where we get our strength from,” his aunt Katherine Whitecloud said. “We have a profound, beautiful history with our ancestors.”

Zach Whitecloud learned of his people’s challenges as well. Indigenous Canadians, much like indigenous Americans, face a number of struggles stemming from centuries of systemic oppression.

That’s why Whitecloud has taken it upon himself to provide a source of positivity. He’s the first member of the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation to play in the NHL, and he doesn’t take that status lightly.

“I truly feel like (I and other First Nations players) represent everyone in North America, from an indigenous standpoint,” Whitecloud said. “I feel we have a responsibility to use our platform to help our people push forward, to help them realize there is hope out there.

“If we can use our platform to motivate, especially the youth, that’s the main goal.”

Growing reach

Whitecloud first became aware of his influence in junior hockey.

He played for the Virden Oil Capitals of the Manitoba Junior Hockey League, a less prestigious stage than the respected Canadian Hockey League, which features the best three junior leagues in Canada.

The upshot was that Virden was located about 30 miles from “home.” It was easy for Sioux Valley residents to watch Whitecloud play, and it was motivating for him to feel their support.

So, Whitecloud gave back in earnest. He spoke at Sioux Valley schools promoting the importance of education and a healthy lifestyle. When he went to college at Bemidji State in Minnesota — located near the Leech Lake Band of Objibwe and the Red Lake Nation — he kept at it.

“Zach was one that he really went above and beyond,” Bemidji State coach Tom Serratore said. “Zach is just there to help people. He helped kids. He looks at himself as a role model, and I think at the end of the day, he realizes playing Division I hockey when he was here, he was in a great situation and a great position to be a good leader and a good mentor.”

Whitecloud also started helping at a hockey camp run by Vancouver Canucks forward — and fellow First Nations player — Michael Ferland. Whitecloud hopes to run a summer camp of his own one day.

“It’s very important to give the kids somebody to look up to,” said Ferland, who has Cree heritage. “Give them a little bit of support and let them know it’s possible for anybody to do great.”

Making strides

Part of the beauty of Whitecloud’s message — of the importance of good habits, of striving for self-improvement — is that he lived it.

He wasn’t a prized prospect. He wasn’t drafted. He had one scholarship offer. Yet somehow he turned himself from a player who, in his own words, “sucked” until he was 18, into one who will appear in NHL playoff games if the season resumes.

His parents taught him the importance of sacrifice, of giving things up (going out, parties) for something you really want (hockey). His billet family — one that houses a junior player — in Virden, Karen and Jack Forster, improved his diet.

Finally, in college, he blossomed. Bemidji State’s coaching staff didn’t know if he even would crack the lineup as a freshman. He ended up on his conference’s all-rookie team after scoring 17 points in 41 games.

“Zach kind of came out of nowhere, and that doesn’t happen many times this day and age,” Serratore said. “He’s earned everything. He wasn’t given one thing.”

A year later, Whitecloud went from surprise freshman to pro prospect. That improbable journey makes what he preaches all the more powerful. Because he practiced it.

“He has a true want to get better,” Knights director of player development Wil Nichol said. “He wants honest feedback. He wants to be a hockey player in every sense of the word. So when you have that, you’re going to get better. You’re going to hit your ceiling.”

Next hurdle

Whitecloud, despite how far he’s come, by no means has arrived.

A good stretch of games doesn’t make an NHL career. He knows this. Which is why he’s not using his extension as an excuse to rest on his laurels.

“I know my role,” Whitecloud said. “I know what makes me a good player, a good person. I know what I can do, and if I can help the team in any way I can to win the Stanley Cup, then that’s the next goal.”

That, and continuing to impact as many lives in his community as possible. That’s what he’s been asked to do as a suddenly public face for his people. It’s a responsibility he isn’t shying away from.

“That’s the expectation,” Katherine Whitecloud said. “That’s what we’re raised with. It’s just a part of who we are to give back constantly. Even if it’s the last glass of water that you have, you give it to whoever walks in your door. You set aside yourself to help others. That’s part of our cultural background and our teachings and how we walk our path in life.”

Contact Ben Gotz at bgotz@reviewjournal.com. Follow @BenSGotz on Twitter.

Indigenous NHL players

— Ethan Bear, Edmonton Oilers (Cree)

— Michael Ferland, Vancouver Canucks (Cree)

— Travis Hamonic, Calgary Flames (Metis)

— Brandon Montour, Buffalo Sabres (Mohawk)

— T.J. Oshie, Washington Capitals (Ojibwe)

— Carey Price, Montreal Canadiens (Ulkatcho First Nation)

— Zach Whitecloud, Golden Knights (Dakota)