How the Golden Knights Victory Flamingo became a sensation

They were on a little losing streak during a season of little losing.

The Vegas Golden Knights had dropped two in a row during the best-ever inaugural campaign of any expansion team in North American professional sports history.

It was March 2018, and the Calgary Flames were in town, burning with vengeance after having lost their two previous games against the home team.

Something had to be done to halt this mini-skid, and season ticket holder Drew Johnson had a plan.

The game was underway. The Knights scored first.

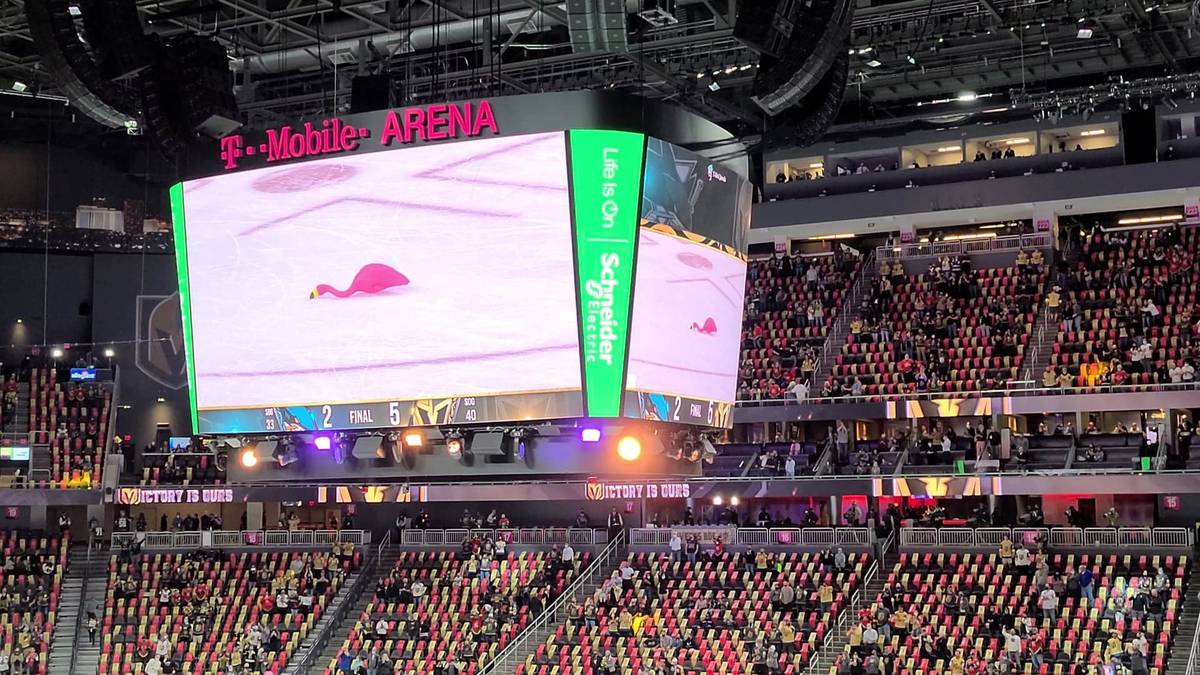

Out came the pink flamingo Johnson had brought to T-Mobile Arena after much deliberation.

He hurled it onto the ice.

“I tossed it during the celebration of the goal,” Johnson recalls in a Southern twang that reveals his Tennessee origins. “I actually threw it on the ice as a rally flamingo. That was the original idea, to try to break the losing streak.”

The Knights caught fire that evening.

Ryan Reaves notched one of his most replayed, highlight-reel hits.

Marc-Andre Fleury earned a shutout.

William Karlsson scored a hat trick.

The Knights extinguished the Flames.

“It seemed to kind of spur something good,” Johnson says. “And then we went on a little winning streak.”

The rally flamingo became the Victory Flamingo, and a tradition was born.

And, oh, how it’s grown since.

Nowadays, fans bring scads of the brightly colored totems to every game, home and away. They dress like flamingos, come clad in flamingo hats and socks.

The Knights gift shop carries flamingo merch; the Victory Flamingo even has its own Twitter page.

Tossing the Victory Flamingo after a win has become this communal thing, a symbol of a city united by sport, a symbol every bit as bright and bold and over-the-top as Las Vegas.

“I actually think it’s one of the cooler things the fans do,” says Knights season ticketholder Patrick Trout. “It’s part of the whole environment and experience that the Vegas Golden Knights have built. It’s such a Vegas thing to do.”

It all began with a deceased mollusk

Before there were plastic pink flamingos in Vegas, there were dead octopuses in Detroit.

The time-honored tradition of hurling stuff onto the ice dates to the 1952 NHL playoffs.

The Detroit Red Wings needed to win two best-of-seven series, a total of eight games, to take home the Stanley Cup.

Because an octopus has eight arms, two brothers chose it as the symbol of the team’s championship quest and tossed one on the ice at the start of the team’s playoff run.

The Red Wings swept the Toronto Maple Leafs and the Montreal Canadiens.

A legend was born.

Other NHL teams followed suit, like the Florida Panthers, whose fans have been tossing plastic rats onto the ice since 1996, the year the team made their first Stanley Cup appearance. The trend began after opening night that season, when forward Scott Mellanby killed one of said rodents with his stick prior to the game and then scored two goals in a Panthers’ win over Calgary.

With the Panthers back in the finals, the rats have returned as well.

And then there’s Nashville Predators, whose fans took to tossing catfish onto the ice.

Not coincidentally, Johnson has ties to the Predators and the Red Wings.

He was living in Nashville, Tennessee, when the city got its NHL franchise in 1998, and his first hockey game was the Predators’ second.

The Predators had a large band of Red Wings die-hards in their fan base, in part because of a Saturn car plant that had opened in Nashville, staffed with relocated auto workers from Detroit.

“There’s this big Red Wings contingent,” Johnson recalls of Predators games back in the day, “and when we would play the Red Wings, they would throw the octopus. Then Nashville sort of came back with the idea of the rally catfish to offset the octopus. That’s what kind of put it in my mind,” says Johnson, who relocated to Las Vegas with his wife, Sarah Johnson, in 2015. “This new team in Las Vegas needs something to throw on the ice to rally the team or signify a win.”

Naturally.

But what to throw?

Definitely something less slimy and more humane than the aforementioned creatures.

“I was always sort of troubled that you would throw a dead animal on the ice, kind of kill an animal for no reason,” Johnson explains.

He and his wife kept deliberating.

They wanted something Vegasy, something kitschy, fun and mildly corny. They thought about fuzzy dice or cards but didn’t want anything too gambling-centric or adult-themed.

“My wife and I kept coming back to the flamingo,” Johnson recalls.

He bought his first one at Star Nursery, the kind with googly eyes that Johnson likes.

Now, it took a minute for T-Mobile Arena staffers to warm up to all the flamingo tossing Johnson inspired.

“After the first toss, a couple of times after that, it was difficult bringing them in,” he says. “Folks had to get creative. There were definitely some flamingos that were mashed down and put in the back of peoples’ pants and down jerseys.”

But after meeting with team officials before the Knights’ second season and explaining his intentions, Johnson saw a change in attitude from arena staffers.

They used to ask him to leave the venue after throwing a flamingo. Now they give him high-fives.

The flamingo takes flight

Johnson’s still tossing flamingos these days.

He and his wife travel to roughly a quarter of the Knights’ road games, with the goal of eventually visiting every arena in the league.

They’ve taken the Victory Flamingo with them.

Johnson has thrown one in New York City’s storied Madison Square Garden, in Winnipeg during the series-clinching win when the Knights earned a trip to the Stanley Cup Final in 2018.

Generally, Johnson says he isn’t hassled by workers or fans at other arenas — though he hasn’t always been greeted so kindly on the home turf of the New York Islanders, the St. Louis Blues or the San Jose Sharks, bitter rivals of the Knights.

“Most folks look the other way,” he notes. “Or they say, ‘Man, I hope you don’t get to use that tonight.’ ”

He’s particularly proud that the tradition has taken root all over the NHL landscape, regardless of whether he and his wife have visited there.

“There are arenas that we’ve never been to, and we’ll sit at home and see the flamingo being tossed,” he says. “That’s really fun.”

For Johnson, the Victory Flamingo is also a means of bridging the gap between spectators and the athletes they’re cheering on.

“Fans can’t go on the ice and celebrate with the players after they win,” he says. “Throwing that flamingo is sort of a way that fans can say, ‘We appreciate you. We know how hard you’re working on the ice.’ It’s a way for fans to almost celebrate on the ice with the players.”

There’s another dimension to Johnson’s appreciation for what the Victory Flamingo has come to represent.

As a political media member who’s written for several publications, including the Review-Journal, he’s immersed in the contentiousness of the left-right divide.

The Victory Flamingo gives him — and the rest of us — a break from all that.

It’s as nonpartisan as it is pink.

“In my job, where it’s media and politics and people who don’t like each other, the thing that I think I love the most about the flamingo is that when we’re on social media, when we have it in the arena, the flamingo is so pure,” he explains. “It’s not political. It’s not negative. It’s a way for people to sort of look beyond the day-to-day differences and realize that we all support the same team, we all love the same city.

“It’s always positive. Unless we’re talking about the Sharks.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter and @jbracelin76 on Instagram.