Dan Wheldon’s fatal crash at LVMS recalled 10 years later

It happened 10 years ago this weekend, but the death of Dan Wheldon in a race car at Las Vegas Motor Speedway is a dark cloud that still lingers.

“It’s part of racing, a bad side of it, and it sucks,” said 2004 Indianapolis 500 champion Buddy Rice in recalling the devastating 15-car crash on Oct. 16, 2011, that claimed the life of the popular two-time Indy 500 winner from England.

Rice vividly remembers riding in an elevator with his friendly rival — they had raced up the ladder to the venerable

Brickyard in virtual lockstep — before the start of the ill-fated IndyCar season finale.

They were to line up side by side in the back row — Rice because of an infraction during his qualification run, and Wheldon as part of a special promotion that would see that year’s Indy winner and a lucky fan split $5 million if he could finish first after starting last.

Rice said he and Wheldon had done some crazy things as their friendship evolved “and he showed me he had gotten a tattoo,” the night before the race.

“Definitely wasn’t Dan’s thing,” said Susie Wheldon, the driver’s widow. “We were at a sponsor dinner at the Palms, and on a whim, we walked into this tattoo place and got each other’s initials tattooed on our wrists. Looking back at what transpired the next day, I’m so grateful for that moment with him.”

‘Felt like a gladiator’

When the green flag fell that next day, drivers and cars darted back and forth as if strung together on a tightwire. Always a charger, Wheldon moved up 10 spots in the first 10 laps.

“Me and Wheldon, we were passing cars … and then there was something huge, right in front of us,” Rice said.

Two cars had touched heading into Turn 1, setting off a massive chain reaction within the tightly bunched field. Cars piled into the retaining wall or each other, leaving parts scattered in their wake. Others flipped or got airborne before exploding into lurid yellow-orange flames.

“It looked like an airplane crash,” said Rice, who thought he had made it through the carnage until a huge chunk of flying wreckage ripped the right rear off his car.

Townsend Bell, who had started 22nd, also was moving to the front when the chaos erupted.

“Four-wide, five-wide, catching huge drafts, basically all 34 cars stacked into one giant blob … it was the closest I ever felt to being a gladiator as opposed to a sportsman,” said Bell, now an IndyCar analyst for NBC.

Deadly blow

Bell said he got spun around in the melee and saw Wheldon’s airborne car coming straight for him as he slid backward against the Turn 2 wall.

“It was going to land right on my head,” Bell said. “I remember lowering my head and closing my eyes. But at that point, E.J. Viso came crashing into me and pushed me out of the way just before Dan’s car came down.”

Bell and Rice walked away. So, remarkably, did 12 other drivers.

All except Dan Wheldon.

The veteran driver steered toward the track apron, only to be launched high in the air after colliding with a slowing car. The driver compartment was facing the track billboards when the car struck the debris fence with deadly force.

A stunned crowd watched in silence as Wheldon was airlifted to University Medical Center, where he was pronounced dead of blunt force head trauma.

He was 33 years old.

He remains the only professional driver in 25 years to have lost his life at LVMS.

‘Worst day ever’

Track president Chris Powell recalls watching the gruesome crash unfold from a control room above the grandstands.

“So often you see these types of things in auto racing, and you’re so relieved when you learn that everyone is OK,” he said. “But about 20 minutes after the crash, my telephone began to ring. When I saw the call was coming from Randy (Bernard, then-IndyCar’s CEO), I said to myself, ‘This isn’t good.’ ”

After interviewing several uninjured drivers as they emerged from the infield care center, pit road reporter and Green Valley High School graduate Jamie Little drove to UMC. She confirmed via telephone to a national TV audience what most already knew.

The race was not restarted. Bagpipes played “Amazing Grace” as the remaining cars lapped the track at leisurely speed in a tribute to Wheldon. The scoring pylon went dark except for No. 77, Wheldon’s number, that was displayed at the top.

“That was the worst day I’ve ever had on the job,” said Little, who called Wheldon a close friend.

The car that he drove to victory in that year’s Indy 500 as well as at LVMS was owned by Las Vegan Sam Schmidt.

“He was the same age I was when I had my accident,” said Schmidt, whose only IndyCar win as a driver came at LVMS shortly before a testing crash left him a quadriplegic. “He had two kids like me, about the same ages. Beautiful wife, just kind of living the dream.”

With the national news media having arrived in Las Vegas to cover a Republican presidential debate, questions arose about the wisdom of running 34 cars — one more than at the Indianapolis 500 but at nearly identical speeds — on a smaller track that left little room for error.

Auto racing on trial

“My thinking was that for 364 days a year, we’re seeking all the national coverage we can get. And if something tragic happens on day 365, we need to be there to make a statement,” Powell said about having to defend the sport after IndyCar officials went into seclusion.

If there were concerns about track dynamics, evenly matched cars, part-time drivers and the $5 million bonus creating a recipe for disaster, Powell said the drivers kept it to themselves.

“There was no real discussion beforehand,” Schmidt said in agreement. “As the weekend evolved and the cars were so competitive and it was flat out, I think there was growing concern. But you talk to (drivers), and it’s safe until you put that helmet on. That’s when the red haze comes, and you’re going to the front on the first lap.”

Rice said pack racing at high speeds is always fraught with risk, but “we did it in Chicago, we did it in Kansas, (running) three-wide and stuff like that. We all know what we are signing up for.”

The obligatory investigation concluded that a “perfect storm” of the rigid debris fence, pack-style racing at high speeds and other factors increased the possibility of a catastrophic wreck.

The cars that raced at Las Vegas were replaced in 2012 by a new chassis that Wheldon helped develop. Renamed in his honor, the DW12 featured bodywork that reduced the likelihood of cars climbing wheels and becoming airborne. Today’s cars also are outfitted with protective driver canopies that probably would have saved Wheldon’s life.

Still, the tragedy ended any thought of IndyCar racing again in Las Vegas, at least on the LVMS oval.

“Our cars are really different now, and I don’t think we’d have the same issues,” Schmidt said of the lingering fear and anxiety. “But it would have to be a street course, just for that reason.”

Legacy continues

Should it come to pass, there might be another Wheldon in the starting lineup. Maybe even two of them. Dan’s boys, Sebastian and Oliver, are now 12 and 10 and racing karts.

“We’ll see where it takes them,” Susie Wheldon said. “Obviously, they aspire to race professionally one day. As they get older, I think they’ll understand things a little more and be able to really decide if it’s something they want to do, or it’s something they feel they have to do to stay connected to their dad.”

The boys were racing in Charlotte, North Carolina, when we spoke, and their mom said she had just received a text from Emma Davies-Dixon, wife of six-time IndyCar champion Scott Dixon, wishing them well.

Dan’s racing rivals, friends and the extended IndyCar family were crucial in helping her and the boys move on without him, she said.

“It’s hard to wrap your head around that it has been 10 years. I still remember very, very clearly being at my house, coming back from Vegas, in my bedroom before the (memorial) service that first week, thinking how am I going to make it through the next day, next year, all of that.

“There are still some deep wounds there. It’s something you never get over; you just kind of learn how to deal with it and move forward the best you can.”

Irreplaceable friend

Susie Wheldon politely declined to speak about the crash itself.

Townsend Bell said his palms still sweat when he thinks about it.

Jamie Little said it had a profound impact on her life at a time when she and her husband, Cody Selman, were contemplating starting a family around her career.

“We were trying to decide when was the best time to have kids,” she said. “Dan was killed, and I went home and said we can’t plan this out. Life is too precious.”

Carter Wayne Selman was born Aug. 9, 2012 — nine months and three weeks later.

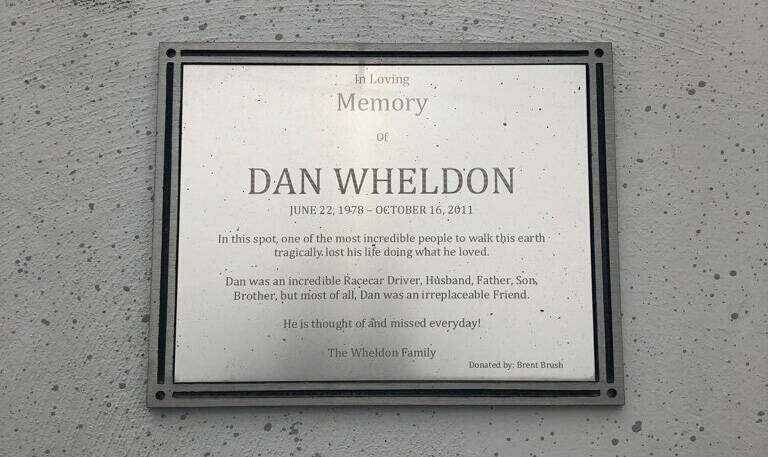

In 2016, Little took a break from her reporting duties on NASCAR weekend at LVMS and joined Wheldon’s friend Brent Brush in mounting a plaque on back of the Turn 2 wall where Dan Wheldon lost his life.

It said he had been an incredible race car driver, husband, father, son, brother and, most of all, an irreplaceable friend who will be thought of and missed every day.

Contact Ron Kantowski at rkantowski@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0352. Follow @ronkantowski on Twitter.

Dan Wheldon file

Born: June 22, 1978, Emberton, Buckinghamshire, England

Died: Oct. 16, 2011, Las Vegas

Accomplishments: Drove for 10 seasons in the IndyCar series. Won 16 races, including the Indianapolis 500 in 2005 and 2011. Was named Indy 500 Rookie of the Year in 2003 and won the IndyCar series championship in 2005. Also won the 24 Hours of Daytona in 2006

Family: wife, Susie; sons Sebastian and Oliver