Dwight Freeney retires after 16 NFL seasons

INDIANAPOLIS — Dwight Freeney mastered the art of spinning long before he reached the NFL.

He kept his body low, his head up and his eyes focused on the quarterback. It made him different, and it made him one of the NFL’s great pass rushers.

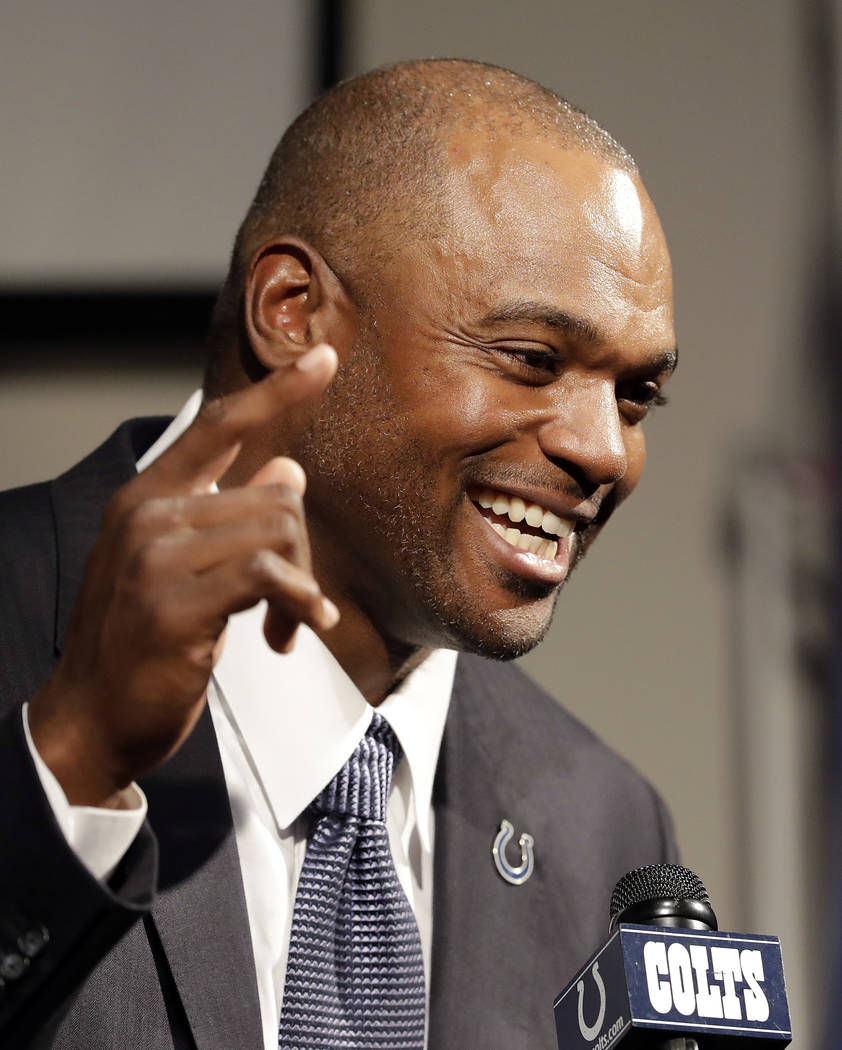

On Monday, after 16 seasons of chasing quarterbacks and making offensive linemen look silly, the former Indianapolis Colts star returned to his adopted hometown to sign a one-day contract to retire with the Colts.

“I used to get called for traveling all day (in basketball), so I couldn’t really do the basketball thing,” Freeney said, explaining why he started using his trademark move.

“So I got on the football field and the coach said ‘Dwight, I don’t care how you get there, just get there.’ So I started using the spin move and kept going with it and it became a natural thing.”

Now, he can finally stop.

Freeney didn’t shed tears or make some long, laudatory speeches. He kept it simple and down to earth — the same way he emerged as a leader in a locker room full of offensive stars.

Instead, his parents, his fiancee, Colts owner Jim Irsay and some former teammates and coaches celebrated the 38-year-old who outlasted and outperformed most of his contemporaries.

He leaves the game with one Super Bowl ring, having played in two other Super Bowls, seven Pro Bowls selections and three first-team All-Pro selections. His 125½ sacks are tied for No. 17 in league history and his 47 forced fumbles rank fifth all-time.

What made Freeney unique, though, was a move so daunting that teammate Robert Mathis incorporated it into his pass rush repertoire and Colts’ coaches actually asked Freeney to teach other linemen how it worked.

“The disrupter, the hurricane whatever you want to call him,” Irsay said. “With Dwight it was like you turn on the film and it was just mayhem. It was like you were instantly drawn to that side of the field. It was like an instant firefight.”

Not everyone appreciated the move.

Defensive coaches outside the organization sometimes scoffed at it, calling it unconventional.

The league’s offensive linemen, meanwhile, feared it because they had to deal with the combination of Freeney’s speed as well as that darned spin. The only thing they lamented more was Freeney’s post-sack military salute.

“People ask me who’s the best defensive lineman you ever played against and it was always Dwight Freeney in practice,” longtime left tackle Anthony Castonzo said during a short highlight film that played before Freeney spoke.

And Freeney believes the Colts’ speed-rushing tandem changed the game.

“I think we created a whole new blocking scheme,” he said. “Before us (Mathis and I), it was just kind of like there’s a running back in the backfield and sometimes the running back would chip us.

“But I don’t remember what team it was, maybe (Jeff) Fisher or (Bill) Belichick and they started bringing a receiver or a tight end to chip us. We weren’t paying attention to a receiver or a tight end and I remember the first time I got chipped by a receiver, my feet were above my head because I did not know he was going to come and chip me. Now they’re everywhere.”

So are guys like Freeney.

When the Colts took him No. 11 overall in the 2002 draft, many analysts criticized Bill Polian for reaching on a player who was too small to defend the run.

But Polian and coach Tony Dungy were attracted to the Syracuse product for another reason.

With Peyton Manning & Co. scoring points by the dozens, they needed finishers on defense — guys who could wreck games when opponents were playing from behind.

Freeney fit the role perfectly.

So did Mathis, who was drafted the next year.

Freeney left Indy following the 2012 season as the franchise’s sacks leader (107½). Mathis claimed the title in 2013 when he had a league-high 19 sacks and became the first winner of the Deacon Jones Award.

The two close friends remain first and second in Colts history, and Mathis, who retired after the 2016 season with 123 sacks.

Freeney received a framed No. 93 jersey and a game ball. But it was the Colts who felt the need to salute the cornerstone of their championship defense.

“I want to thank the opponents I played against because I always had to bring my A-plus game,” Freeney said. “The Jonathan Ogdens, the Drew Breeses, the Tom Bradys. Those guys made me bring my A-plus game every time.

“It raised my competitive nature to places I never knew existed. Tom, even though you beat me more than I beat you, I want to thank you for that and I’m going to miss those battles.”