Being undrafted can be preferable to going in the 7th round

Every player who enters the NFL will tell you that he dreamed of hearing his name called during the draft. That will certainly be the case in Saturday’s final round of the 2020 event.

There’s a certain panache to it. But when the draft is nearing its end, being bypassed can be a blessing in disguise.

When a player is drafted, they have no choices — they are to report to the team that chooses them. Based on the collective bargaining agreement, the player’s salary is slotted within a strict range. Particularly for the late-round draft picks, there isn’t much to negotiate in a player’s first professional contract.

But if a player goes undrafted, he has leverage because he decides where he wants to go. If there’s a favorable situation for him to make the 55-man roster at the end of training camp, that’s where the player may want to sign.

For example, last year, the Raiders selected linebacker Quinton Bell with the 230th overall pick which came midway through the seventh round. But Bell did not make the final 53-man roster.

Fullback Alec Ingold, however, did make the roster after signing with the club as an undrafted free agent. He received a $10,000 signing bonus to join the team — a typical amount for an undrafted free agent. A team may offer that player more guaranteed money than he would receive for being a seventh-round pick.

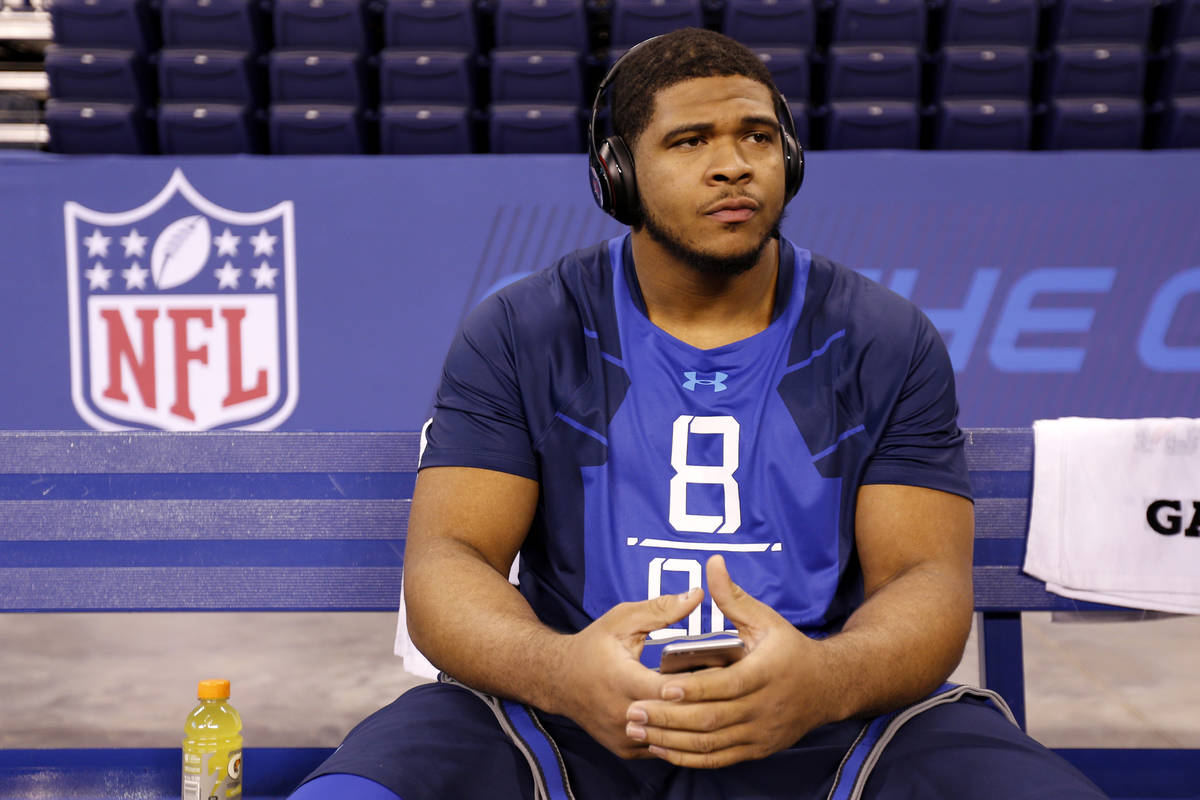

One of the best illustrations of why a player would want to go undrafted came in 2015 with former LSU offensive lineman La’el Collins.

Collins became embroiled in controversy just a few days before the draft when a pregnant woman with whom he’d had a relationship was shot to death. Collins was not a suspect, but he did have an interview scheduled with police. That tanked Collins’ draft stock — plummeting him from a likely top-10 pick to way down on teams’ boards, if not off them completely.

Once Collins fell out of the first round, his agents publicly said that if he wasn’t drafted in the second or third round, Collins would sit out the season and re-enter the 2016 draft. Their goal was to get Collins to become a free agent, where he’d be on the open market.

The strategy worked, as Collins went undrafted. Not that he was ever a suspect, but Collins was cleared of any wrongdoing after meeting with police. He then went on a bit of a free agency tour and settled on signing with the Cowboys for a fully guaranteed deal of $1.6 million, with a $21,000 signing bonus. By comparison, running back Todd Gurley — the No. 10 pick of the draft — received a fully guaranteed $13.8 million in his rookie contract.

But Collins did play well enough to earn an early second contract, signing a two-year, $15.4 million extension in August 2017. Had he been drafted, Collins wouldn’t have been able to receive an extension until the 2018 calendar year. Then Collins signed a five-year, $50 million extension, with $35 million guaranteed, prior to the start of the 2019 season.

Collins is an extreme case, but his contract structure and ability to get more money sooner in subsequent deals made his agents’ strategy on draft weekend in 2015 a smart one. It’s also why at a certain point, while it’s nice to hear one’s name called, it might be more lucrative to enter the league as an undrafted free agent.