Hard-hitting safety Jack Tatum left mark on Raiders franchise

Editor’s note: This is part of an occasional series acquainting fans with the Raiders’ illustrious 60-year history as the team moves to Las Vegas for the 2020 season.

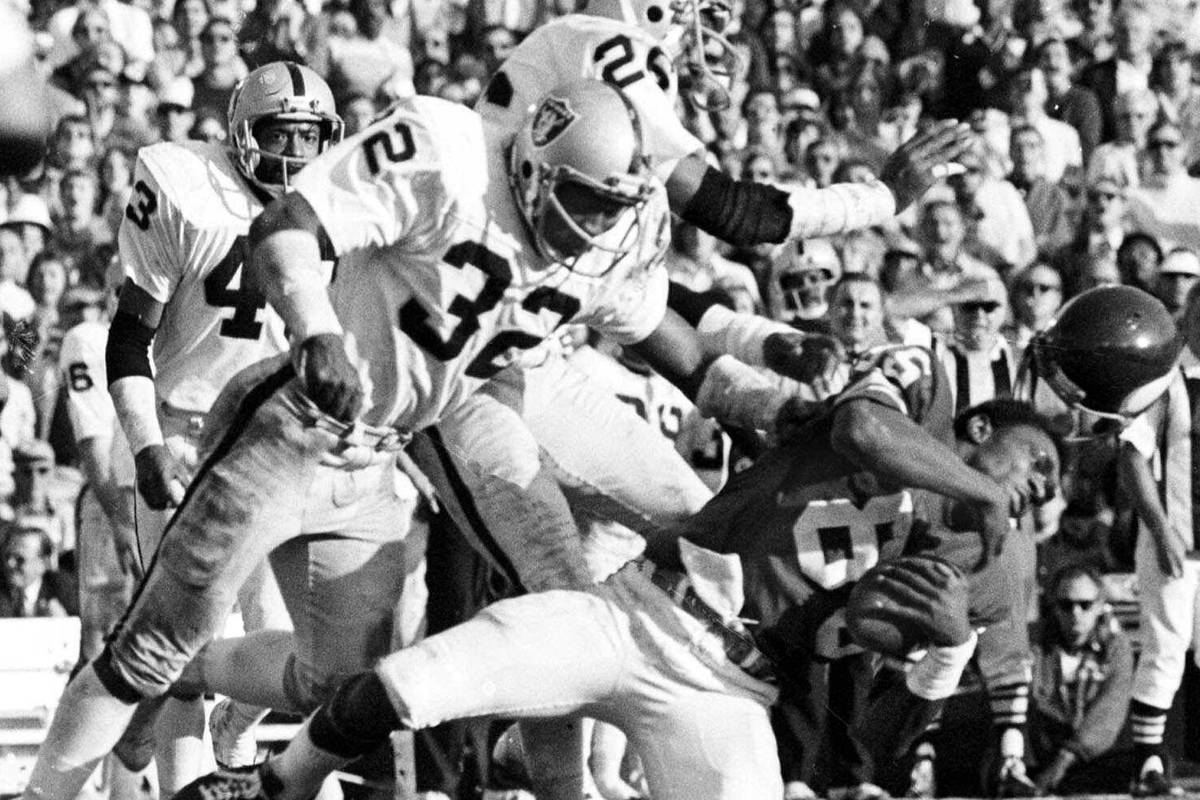

As one of the anchors of the legendary “Soul Patrol” secondary, safety Jack Tatum laid a whole lot of hard hits throughout his career with the Oakland Raiders. Three in particular stand out.

There has rarely been an NFL highlight reel of big hits that didn’t feature Tatum’s hit on Minnesota’s Sammy White in the 1977 Super Bowl that sent the receiver’s chin strap and helmet flying from his head in opposite directions.

It was also Tatum who sent Pittsburgh’s Frenchy Fuqua flying as he tried to break up a pass that set up the “Immaculate Reception” in a 1972 playoff game. The chaos resulted in a controversial win for the Steelers on what was named by the league in 2019 as the top play in NFL history.

The third hit had far darker consequences.

Tatum laid a hit on New England’s Darryl Stingley in a 1978 preseason game that broke the receiver’s fourth and fifth vertebrae and left him almost completely paralyzed from the neck down.

It changed both their lives. While Tatum and Stingley never connected after that day and Tatum declined to apologize on several occasions, he did address the pain the play caused him in his 1980 book, “They Call Me Assassin.”

“When the reality of Stingley’s injury hit me with its full impact, I was shattered,” Tatum wrote. “To think that my tackle broke another man’s neck and killed his future.”

He expounded on that in 1996 in his third and final book, “Final Confessions of an NFL Assassin.”

“I was paid to hit, the harder the better,” he wrote. “I understand why Darryl is considered the victim. But I’ll never understand why some people look at me as the villain.”

After Tatum died of a heart attack as he awaited a kidney transplant at 61 years old in 2010, his longtime friend and former Ohio State teammate John Hicks told the Associated Press the play haunted Tatum.

“It was tough on him, too,” Hicks said. “He wasn’t the same person after that. For years he was almost a recluse.”

Tatum was born in North Carolina, but didn’t start playing football until high school in Passaic, New Jersey. His athleticism and raw talent helped earn him a scholarship from Woody Hayes at Ohio State, where he was recruited as a running back before assistant coach Lou Holtz convinced him to switch sides of the ball.

The move worked out. Tatum was named a unanimous All-American in 1969 and 1970, even picking up a few Heisman Trophy votes as he helped Ohio State to two national titles.

The Raiders selected him in the first round of the 1971 draft. He spent nine years in Oakland before finishing up his career with one season in Houston.

He set a record with a 104-yard fumble return for a score that wasn’t tied for 28 years.

Tatum teamed with safety George Atkinson and cornerbacks Willie Brown and Skip Thomas to form one of the most memorable secondaries in league history. He was ranked as the sixth-hardest hitter ever in the league by NFL Films and elected to three Pro Bowls.

Footage of his best hits, which were legal at the time, could serve as a blueprint for what modern-day players are no longer allowed to do. Sometimes it doesn’t even look like the same game that is played today.

“I like to believe that my best hits border on felonious assault,” he wrote in 1980.

Atkinson had a firsthand view of many of them.

“Guys didn’t want to come across the middle because getting hit by him was like getting hit by a truck,” he once said. “He was devastating with his timing and his angles of contact.”

Tatum, who was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in 2004, helped the Raiders to a victory in Super Bowl XI.

Contact Adam Hill at ahill@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AdamHillLVRJ on Twitter.