Ryan Reaves understands both sides of police and protests

Conflict is inevitable when your heart beats for both sides of a polarizing movement.

That’s where Ryan Reaves finds himself after the death of African American George Floyd that resulted in a second-degree murder charge against a white Minneapolis policeman.

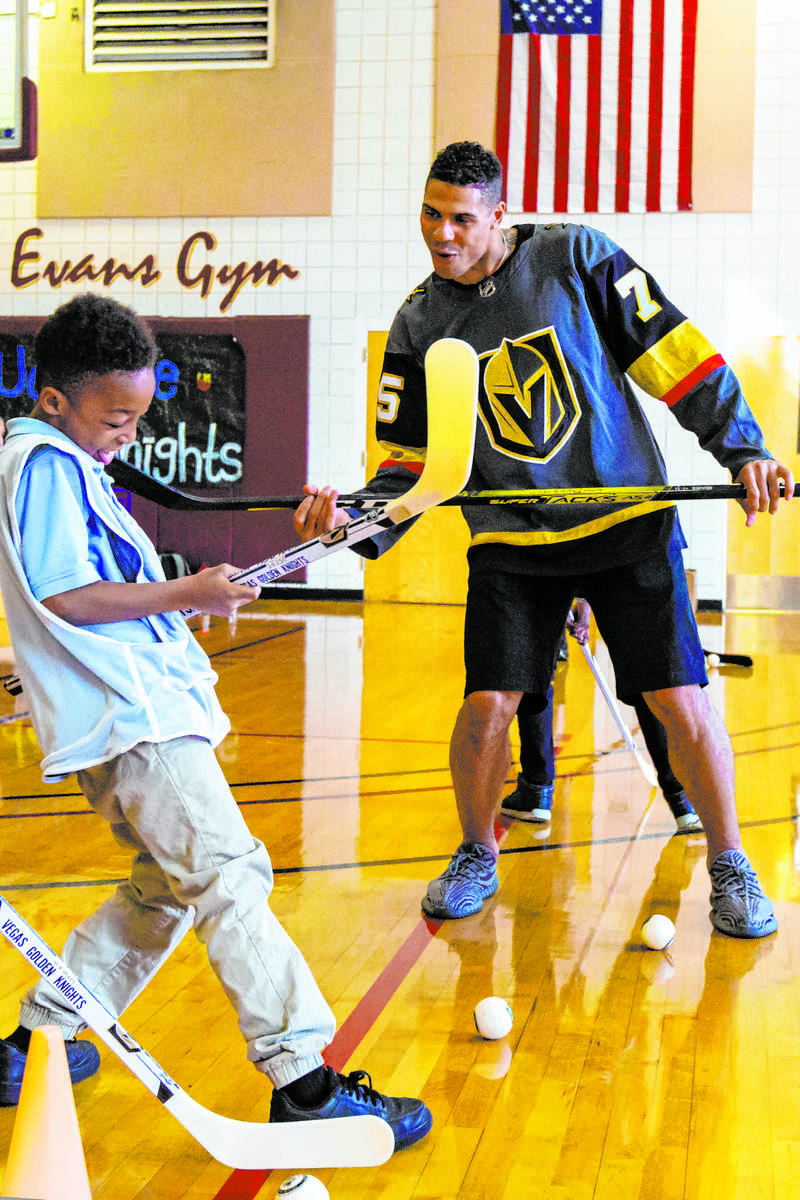

A forward for the Golden Knights and one of the few black players in the NHL, Reaves is also the son of Willard Reaves, a former sergeant with the Manitoba Sheriff Services in Winnipeg.

He is also the great-great-great-grandson of Bass Reeves (his last name spelled differently when he was born a slave in 1838), the first black deputy U.S. marshal

west of the Mississippi. Nearly a century before the fictional character was introduced as a white man wearing a mask and sitting atop a white horse, history has viewed Bass Reeves as the first Lone Ranger.

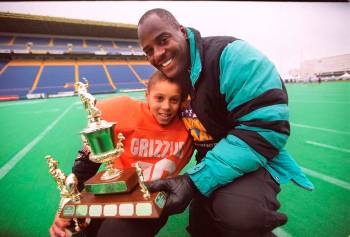

“(Law enforcement) in our family dates a long, long ways back,” Willard said. “We have several who chose this as (a profession). Because of this, Ryan can see all of this from both sides. He’s mixed race (his mother Brenda is Caucasian). He can analyze and internalize from either point. He will come to his conclusions. He will deal with the facts and what he sees and hears.

“And there is internal conflict.”

It can’t be easy. It has to be gut-wrenching at some level. Whatever the number of professional athletes whose family members serve in law enforcement, they must be dealing with a whole different set of emotions than their teammates right now.

For all the moments of levity Reaves provides on and off the ice, all those skirmishes in which he happily engages opposing players, there isn’t a more thoughtful and perceptive player within the Knights locker room. None are more willing to talk.

Hockey has forever been viewed as a world enveloped in racism. Advancement on this front has been excruciatingly slow. Even as the issue seemed to generate progress of late, intolerance remains a central characteristic.

But with recent NHL incidents regarding racial injustice and those protests following Floyd’s death, some players have gone public with their feelings and opinions. That’s a good thing.

But most haven’t. That’s an expected thing.

Athletes speaking out

It was Thursday when Golden Knights forward Mark Stone told reporters the team had spoken internally about the tumultuous reaction to Floyd’s death, but that for now it preferred to sit back and listen instead of entering a public conversation.

In the moment, it was such a hockey thing to say. Just another example of a reluctance by NHL players to take on the most controversial issues. Most don’t even take on the trivial ones.

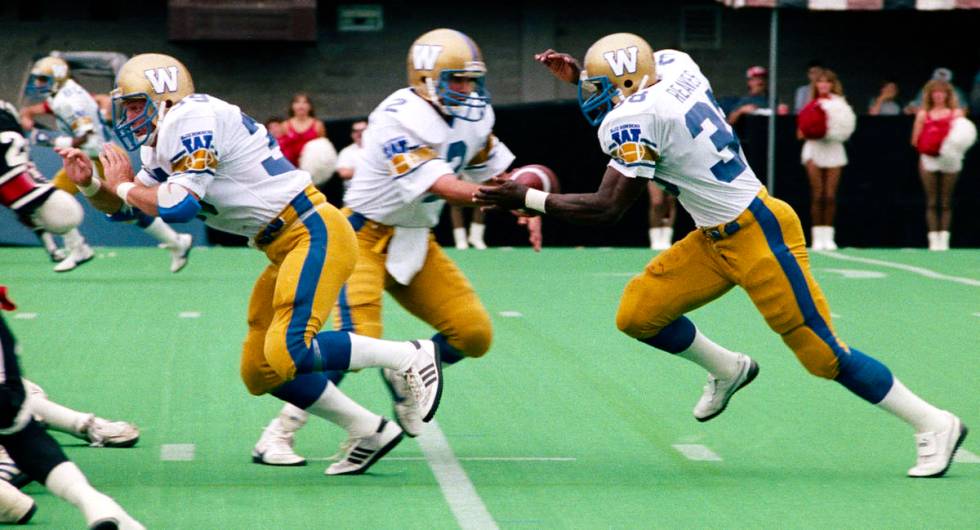

Reaves sees it differently. His brother, Jordan, a defensive lineman in the Canadian Football League, has been extremely outspoken on racial issues across Twitter.

“My brother plays a predominantly black sport and that can add fuel to the fire when you have a black issue among a lot of black people. They get a little more fired up because they’re in it together,” Ryan said.

As a result, he said his brother “is a little more outspoken than I am. He’s very passionate about this. I’ve had multiple conversations with him and in one, I just sat there and listened. Even though he’s my brother and we’re both black, sometimes we need to just sit down and listen. I think that’s a very big message that needs to keep getting thrown out there. It’s time for people to listen.”

That’s certainly true in hockey. “You’re coming from two different sides of the fence here,” Ryan said. “In hockey, it’s a predominantly white sport, so for a bunch of white hockey players to come out and speak about black issues, it’s probably tough for them. It’s not an easy subject to talk about, but I like how a lot of players are going about it.

“They don’t like what has been going on and now it’s time for them to listen. That’s a powerful thing. They’re saying, ‘We need to listen and learn from this.’ And they have a platform that will reach hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people.”

Reaves and … Kane?

The videos of those rioting and looting and injuring others trying to protect what they spent lifetimes building shake Ryan Reaves. The images of police shooting rubber bullets into crowds and forcefully restraining those protesting anger him. The ones of officers walking hand-in-hand with those doing so peacefully encourage him.

An internal conflict rages on.

In the most ironic of ways, what has become one of the more extensive beefs among two NHL players has forged a common bond.

Reaves and Evander Kane of the San Jose Sharks won’t be sharing Christmas cards any decade soon, but it is the latter who led the formation of an alliance meant to “eradicate racism and intolerance in hockey while promoting diversity at all levels of the game.”

“I spoke to Evander and told him I want to jump in on this powerful message,” Reaves said. “We have to put aside our differences on the ice and come together for a much bigger cause.

“You definitely have to understand what your beliefs are and where you stand. At the same time, I do kind of toe both lines because I have had great experience with cops. I’m also very aware of what’s going on around the United States.

“A lot of it stems from undertrained ignorance that every police force seems to have some — 1, 2, 3, 4 cops — whatever the number is. The thing is not to let those bad apples trickle through an entire force.”

Lone Ranger

It was in 1875 when a legendary lawman of the Wild West was tasked along with 200 other deputy marshals with bringing in countless thieves, murderers and fugitives who had overrun an expansive 75,000-square-mile Indian territory in what is known today as Oklahoma.

A faithful defender of the government that failed to protect his freedom at birth, the lawman was said to have killed 14 outlaws, arrested 3,000 more and all without sustaining a single wound.

He was the great-great-great-grandfather of Ryan Reaves.

“The world is different now than at that time and in many ways the same over what we’re fighting for,” said Willard Reaves, who grew up four hours from Las Vegas in Flagstaff, Arizona, and played football at Northern Arizona University. “Every single person on this planet saw what happened to George Floyd. A police officer murdered a person. Pure murder. It’s something we all have to deal with internally and finally acknowledge what has been happening for way too long. This was not serving and protecting.

“This will change everything. This has struck a nerve like nothing before. Ryan is like myself and his family and everyone else right now.

“Plain and simple, we all have to put a stop to this.”

Contact columnist Ed Graney at egraney@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4618. He can be heard on “The Press Box,” ESPN Radio 100.9 FM and 1100 AM, from 7 a.m. to 10 a.m. Monday through Friday. Follow @edgraney on Twitter.