Earthquake during World Series still resonates 25 years later

Here it is, the middle of October, and there’s no baseball today. This is what baseball fans get when the Royals — the Royals?! — and Giants take care of business early, albeit in the most dramatic of fashions.

Twenty-five years ago Friday they didn’t play baseball, either.

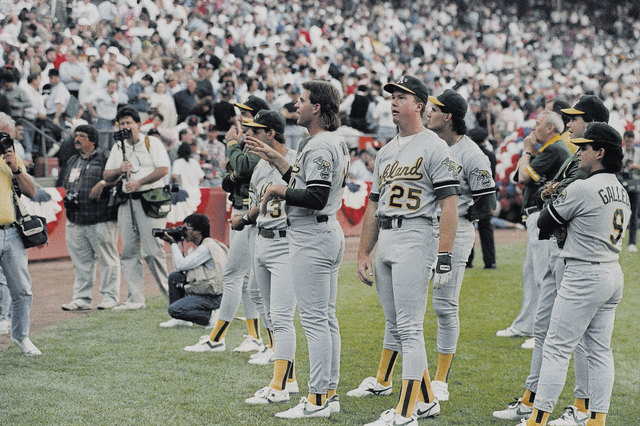

The Giants and A’s were supposed to play Game 3 of the World Series on Oct. 17, 1989. They were calling it the Bay Bridge Series; the BART series, for the Bay Area Rapid Transit buses linking the two cities; the Battle of the Bay.

They called it that until 5:04 p.m. on that afternoon a quarter-century ago, until the ground began to shake.

It already had been a hectic day on the sports desk at the Marin Independent Journal. By then, Matt Young of the A’s and Mike Krukow of the Giants had filed their guest columns — this World Series was such a big deal in the City by the Bay, and in Oakland, that the newspapers had hired ballplayers from each side to write about it in their own words.

Young’s story began with “I took a limo to the park …”

Krukow’s, on the other hand, was insightful and funny and glib. Mark Whittington, then sports editor at the Marin newspaper, now sports and features editor at the Review-Journal, remembers telling Mike Krukow that he was a natural, that if he couldn’t come back from rotator cuff surgery, he should consider becoming a broadcaster.

Just before Game 3 was to start, Al Michaels’ voice went up an octave, as if he was calling hockey in Lake Placid again. “I’ll tell you what, we’re having an earth- …”

And then his voice broke up, and the pictures, descriptions and accounts of the game got all wonky.

The A’s Rickey Henderson was in one of the restroom stalls in the visitors’ clubhouse, according to the new ESPN “30 for 30” documentary about “The Day The Series Stopped.” Henderson said he often got nervous before big games. When he heard the rumble, he thought it was only Giants fans getting all riled up.

Mark Whittington was on the phone with sports columnist Dave Albee when the screen went dark and the newsroom started shaking like a bowl of Jell-O.

“Earthquake,” Albee said, fairly calmly.

“Whatever you do, don’t hang up,” Whittington said.

The agate clerk at the newspaper office sought refuge under a desk.

Albee stayed on the phone, because you never know when you might get another line after an earthquake. Other reporters used him as a proxy to report on the scene at Candlestick Park. Chunks of concrete were falling from the upper deck. Players’ wives were passing players’ children down to the ballplayers on the field. It seemed safer down on the field.

Images began to form, images one doesn’t forget, like a line drive or a Texas Leaguer in the next day’s box score. Some chucklehead was climbing one of the light standards, which seemed a wacky thing to do under any circumstance, much less during an earthquake.

The power went out.

Dave Albee continued to work on his game notes, until it got dark and they threw him out of the ballpark. Then he lit them on fire. The flame from his story helped him see where he was going.

In the manner of ballplayers who are thrust into clutch situations, the baseball writers rose to the occasion. They became reporters and conduits of a much bigger story. When the going got tough — when the ground started to shake as if Mark McGwire and Jose Canseco had injected it with something — they got going.

Dave Albee stayed on the line.

Jerry Izenberg, the Hall of Fame sports writer who makes his home in Henderson, wrote his story while sitting on a curb outside Candlestick Park beside a bus. When it got too dark to see the keys, he gave the bus driver $10 in return for her turning on the lights.

Izenberg made his deadline.

After deadline, a taxi driver was promised $100 if he would take Izenberg to the Nimitz Freeway, where a section of bridge had collapsed. Longshoremen pulled a man from his crushed car, still alive. The longshoremen thrust their fists into the air.

That was the lead paragraph to Izenberg’s follow-up story.

Review-Journal colleague Norm Clarke was covering the series for the Rocky Mountain News in Denver. Clarke wrote on Friday about interviewing an 89-year-old man who was trying to recover belongings from his apartment in the Marina District. The man told Norm this wasn’t his first earthquake. He had survived the Big One in 1906, when he was 6 years old.

Royce Feour, the R-J’s retired Hall of Fame boxing writer and a devout Giants fan, was in the ballpark that day, too. He had tickets for Game 3. When the ground began to rumble, Feour made mental notes. When he got back to the San Francisco Hilton and telephone service was restored in the lobby, he called the newspaper office to dictate a story. On his vacation.

On Friday, he posted on his Facebook page the story he had called in 25 years ago: “It’s like the Twilight Zone, except the people here are living it.” That was Feour’s lead. He wrote it without spell-check, a laptop or electricity.

He, too, had stayed on the line.

By then, bridges had collapsed. Cars were falling from the top level of the Bay Bridge to the bottom. Certain districts were on fire.

People were dying.

Sixty-three people would die in the Loma Prieta earthquake. There were 3,757 injuries. There would be no baseball for 10 days.

Mike Krukow would go on to become a broadcaster.

For its documentary, ESPN spoke with the chucklehead who had climbed the light standard. He had drawn the short straw when a wind sock had gotten tangled way, way up there.

The fellow’s name was Benjy Young. He was way, way up there at 5:04 p.m. on Oct. 17, 1989, when the ground began to shake.

“I was sure I was going to die,” he said.

Twenty-five years later, Benjy Young was still clenching his teeth and fists when he told his story, a story that in retrospect makes the great Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson seem like a wuss.

Las Vegas Review-Journal sports columnist Ron Kantowski can be reached at rkantowski@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0352. Follow him on Twitter: @ronkantowski.