Though his life was short, Mehdi Bouras’ time was all aces

It was a beautiful Thursday afternoon, warm and sunny and idyllic, and the UNLV men’s tennis team was knocking the fuzz off the bright yellow-green ball against UNR.

This would be a 5-2 victory for the Rebels, their 11th this season at the Fertitta Tennis Complex without a defeat. It would give UNLV a few more points in the Governor’s Series, this new across-the-board athletic competition between scholar-athletes who wear scarlet and gray and those who wear navy blue and silver.

But on this day the UNLV players wore white shirts and black shorts, and on the sleeves of their tennis shirts were little black circles with the initials “MB” done in white. And that’s why the score, and the Governor’s Series points, and the idyllic weather mattered nothing.

None of it mattered. Not even the billowing cloud of charcoal-gray smoke rising from the old Key Largo casino down the road mattered.

MB was Mehdi Bouras, the 2011 Mountain West men’s tennis player of the year, one of the most decorated tennis players in UNLV history.

It had been exactly a week since he had died.

The 24-year-old native of Algeria, with layovers in Oman, Paris and Versailles, was ranked No. 986 among Association of Tennis Professionals in singles, No. 1,321 in doubles, when he took ill after a first-round loss at a futures tour tournament in Costa Mesa, Calif.

Within hours he was dead, of meningococcal meningitis, a virus that attacks the central nervous system almost without warning and totally without mercy.

Now instead of 986 and 1,321 in the computer, Mehdi Bouras is No. 1 in the hearts of Rebels who wield huge rackets made of graphite and titanium, and in the hearts of many other Rebels who don’t play tennis.

And now lots of people are speaking of perspective, which is good to have, but sometimes comes at a terrible price.

“Everyone who met him, loved him,” said a small man with sad eyes. This was Owen Hambrook, the UNLV coach, who called this his darkest week. Hambrook had lost his parents to cancer, but they had fallen in love, married, raised children. They had full lives.

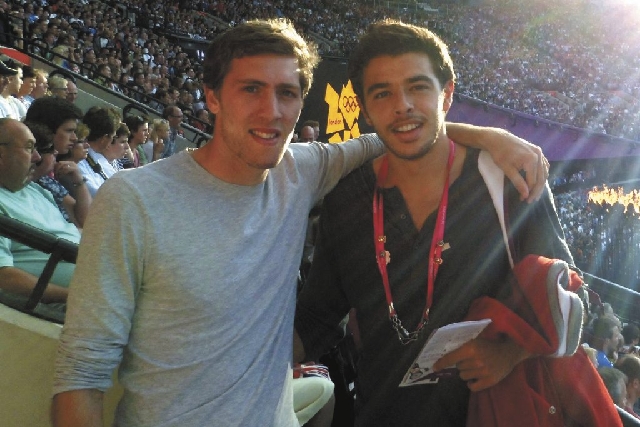

Alex Bull loved Mehdi Bouras. They were UNLV teammates, and Mehdi crashed at Alex’s home in Wimbledon during the London Olympics.

They went to the track and field events. When Taoufik Makhloufi won Algeria’s first-ever track and field gold medal in the men’s 1,500, Mehdi pumped his fists; afterward, when they played the Algerian national anthem, Mehdi tried to sing along. But Alex said Mehdi didn’t know the words.

Alex said a lot of people didn’t know that Mehdi’s parents left Algeria when Mehdi was 6 years old.

This was a young man with a future so bright that shades and SPF-50 sunscreen wouldn’t have been enough. He was a student-athlete in the strict sense, a two-time Intercollegiate Tennis Association scholar-athlete, three-time all-academic Mountain West honoree, the 2009 UNLV Most Outstanding Scholar-Athlete.

So here’s a kid who had everything — looks, brains, wicked groundstrokes — and then suddenly he’s not feeling well, and then they’re calling for an ambulance.

And then on Sunday night, at a memorial service at the tennis courts, UNLV athletic director Jim Livengood is speaking into a microphone in somber tones, because his tennis coach is too choked with emotion to continue.

“It’s hard to understand, when you go through this, particularly with young people, because this is not the order of things,” Livengood said.

Not the order of things.

Livengood nailed it, with those five words serving as a profound hammer.

The order of things was out of whack again the day before the UNR match, when Rachid Bouras, Medhi’s dad, a physician for the national sports federation in Qatar, stopped at the Fertitta Tennis Complex after identifying his son’s body and whatnot in California.

Seeking closure among Mehdi’s friends, Rachid Bouras broke down, too, and then so did the Rebels again. It made your heart hurt, Owen Hambrook said.

My first recollection of Mehdi Bouras was 2010, after the U.S. soccer team drew Algeria in the World Cup, and I wanted to speak to an Algerian about Algerian soccer, and sand dunes, and sheiks, and mysterious women shrouded in veils, and hijackers flying airplanes there. And camels.

This was my unenlightened perception of Algeria.

He was off playing tennis in Paris then, but after he blossomed into one of UNLV’s very best, I wrote about him again in 2011 — not because he was an Algerian, though I found that interesting, but because he had just qualified for the NCAA championships in both singles and doubles, which is pretty much unheard of around here.

We sat on the sofa outside Owen Hambrook’s office, and I remember how introspective this young man was, how he chuckled softly when I asked about the camels. And that one of the last things he would do before leaving tennis practice is check that none of the Rebels had left the water running in the shower. Because where he came from, water was a valuable resource not to be wasted.

If you knew him, you loved him. That’s what Owen Hambrook said. That’s what a lot of the Rebels I spoke with said while other Rebels, the ones wearing Mehdi Bouras’ initials on their sleeves, were knocking the fuzz off the bright yellow-green ball against UNR.

Las Vegas Review-Journal sports columnist Ron Kantowski can be reached at rkantowski@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0352. Follow him on Twitter: @ronkantowski.