Umpire’s son knew little about his dad or his line of work

When I was 12, I knew all the umpires.

Shag Crawford. Emmett Ashford. Nestor Chylak. Satch Davidson. Augie Donatelli. Tom Gorman. Bill Haller. Chris Pelekoudas. Ron Luciano. Frank Pulli. Ed Runge. Marty Springstead. Harry Wendelstedt. Big Lee Weyer, who sometimes during a rain delay would join Jack Brickhouse in the broadcast booth and perform card tricks.

These were familiar names then. They remain familiar to me now.

So I knew of Tony Venzon, remembered his name along with those of the other men in blue. Or men in maroon, if they were American League umps in the 1970s.

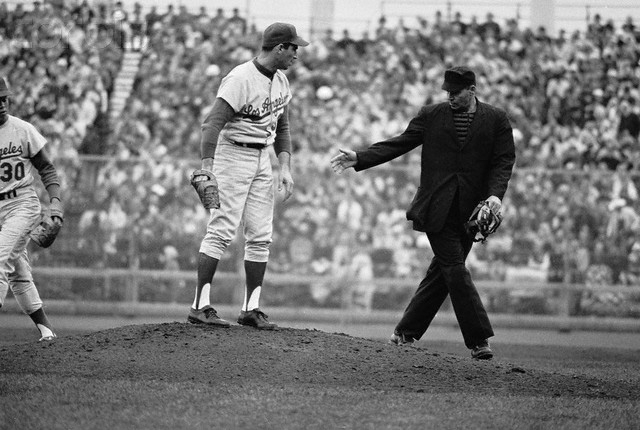

Tony Venzon umpired in the National League from 1957 until 1971. He died on Sept. 20, 1971, from complications of heart surgery, at Shadyside Hospital in Pittsburgh. He was 56. The obituary from the wire service said he left a wife, Kaye, and a son.

The son was not named in the obit.

Tony Venzon’s son was named Lawrence. Everybody called him Bud. When I returned from the Indianapolis 500, there was a voice mail from Bud Venzon, who lives west of the Silverton Casino in a sprawling ranch home, the kind where you could keep horses out back, if you wanted.

Bud Venzon said he wanted to show me something.

When I drove out to his place, there were lots of ranch homes with dusty corrals, and one with a batting cage. I figured that might be Bud’s place. Actually, Bud’s place was across the gravel road.

Bud was sitting at the bar in his giant man cave, watching NASCAR with the sound turned down. A column I had written about Stan Musial after he died was on the bar in front of him. That column was written in January. It might have been the most recent thing in Bud Venzon’s man cave.

There were two ATVs and a 1967 Lincoln Continental. Behind that, a ’48 Lincoln and a ’75 red Corvette. The cars looked immaculate. Bud said it had been years since he’d driven them.

In a cabinet on the far wall were die-cast models of the fire trucks Bud drove and the F-105 Thunderchief fighter jets he turned wrenches on at Nellis Air Force Base.

Bud had tacked up newspaper clippings of fires he had fought. A huge front-page photo, five columns, shows water dripping from his head. Bud looks just like Sam Elliott, the actor, in that one. The clipping has turned silver-yellow, the same color as Bud’s ponytail.

He pulled out a laminated newspaper story from the Chicago Tribune. It was a column about his father, written five years after his death, about a ballgame played on July 23, 1962, Cubs vs. Phillies, at Wrigley Field.

The satellite Telstar had been launched — perhaps you recall the record by the Tornados, which inspired Bruce Springsteen’s anthem “Born to Run” — and it was decided to beam part of the ballgame around the world, via satellite.

A small part of the game. Jack Brickhouse told Tony Venzon, who was calling balls and strikes, they had only 90 seconds. Brickhouse was worried that nothing would happen during those 90 seconds, that perhaps the batters would just look at balls and strikes or scratch a lot in the on-deck circle.

Tony Venzon told Brickhouse not to worry. He’d take care of it.

Tony Taylor swung at the first pitch and flew out to George Altman in right. Johnny Callison swung at the first pitch and singled to right. It was the longest single in baseball history. People saw it in Stockholm and Rome and Budapest.

The newspaper account said Jack Brickhouse told Tony Venzon how lucky they had been. Lucky, hell, the umpire said.

He had told the Phillies about Telstar and that they had better come up swinging, because he was going to call every one of Cal Koonce’s pitches a strike if they didn’t.

In 1969, Tony Venzon became the only umpire in history to witness no-hitters on consecutive days. He was at third base, umpire-in-chief, for Jim Maloney’s gem against the Astros and at second base the next day, when Houston’s Don Wilson turned the tables on Cincinnati.

Tony Venzon also was the only umpire to kick the great Hank Aaron out of a major league game, for arguing balls and strikes on June 19, 1966.

That was news to Bud Venzon. All of it was news to Bud Venzon, who wasn’t a ballplayer, knew little about the game, knew little about his father. Other than his father was never home, because umpires do not have home games.

He recalls going deer hunting with his dad, picking him up at Forbes Field a time or two, his dad getting up at dawn to go to work in the coal mines near Johnstown, Pa., during the offseason, because in those days, ballplayers and umpires had to take offseason jobs to support their families.

So Bud Venzon, who will turn 72 in a couple of weeks, didn’t really get to know his father after the World Series either.

“It’s sad,” he said through thin lips and a bushy mustache that combined with his cowboy hat and ponytail make him look like a prospector during the Gold Rush.

I agreed. I said something about how difficult it must be for a little boy to grow up without a father’s guidance and whatnot, and that’s when Bud Venzon said no, no, no.

“It was sad for him because he had a son who didn’t give a damn about baseball.”

Las Vegas Review-Journal sports columnist Ron Kantowski can be reached at rkantowski@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0352. Follow him on Twitter: @ronkantowski.