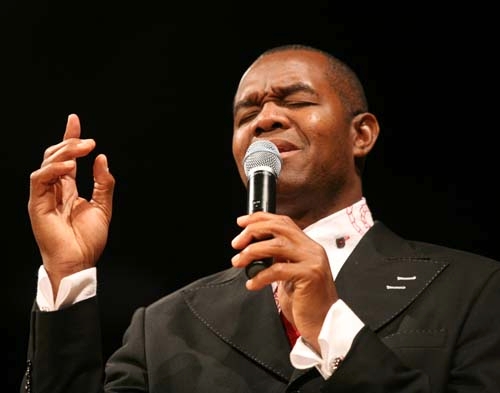

Ex-NFL quarterback Cunningham now calls plays for Henderson church

It's Super Bowl Sunday, a day that eluded Randall Cunningham throughout his 16-year NFL career, a day a team nicknamed the Saints would win the big game, and Cunningham's message to his church, Remnant Ministries, is accountability.

"You can't," he says, wearing a black shirt, black vest and red tie, "halfway commit to God."

But Cunningham didn't expect his own commitment to run this deep. Becoming a pastor is not what he envisioned or even wanted.

He thought his days of working on Sundays were over.

"Because I thought right after football, you ride off into the sunset and go golfing every day," Cunningham said. "But that was an empty life."

So here he is, quarterback of a different type of team. Cunningham no longer guides 300-pound offensive linemen and ego-driven wide receivers to victories on the field. Today, he counsels and encourages troubled teenagers, middle-class families worried about paying the mortgage and anyone else willing to enter the Protestant interdenominational church on Windmill Lane.

And plenty have come, even those who were raised in Catholic, Mormon or Jewish homes. Not even 6 years old, Remnant Ministries keeps outgrowing its surroundings, and plans are being made for a new, larger building.

Some come to see Cunningham, the ex-NFL and UNLV quarterback. Many stay because of Cunningham, the preacher.

The two identities are interlocked.

"If I'd never played football, I don't think I'd be the leader I am today. If I hadn't gone through the hardships I've gone through and been rebuked and hated by the Giant fans and the Cowboy fans and the Raider fans,'' he said, laughing, ''I would not have been nourished in the area of maturity."

■ ■ ■

No road-to-Damascus event -- the story of Paul, probably the Bible's most dramatic conversion story -- put Cunningham on his current course. He grew up in Santa Barbara, Calif., attending a Baptist church because his mother, Mabel, insisted. She was the family backbone, the one who made sure Cunningham and his three older brothers took care of their chores. Their father, Samuel, was much more laid back, but he flashed a temper from time to time.

Even though he was raised to know that Sunday meant going to church, Cunningham didn't understand what the Christian faith was truly about. But his curiosity was stoked while attending the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and working as a runner at R&R Advertising, where he got to know Tom Cameron, the creative ad director who now is a minister.

Their conversations weren't deep or detailed, but Cameron told him he believed it was important to look to God for answers.

"I wasn't being overbearing," Cameron said. "I didn't want, as a friend calls it, to be a jock sniffer. I liked Randall because I liked Randall. I cared about the man, and I think he saw that."

Their relationship continued even after Cunningham was drafted in the second round in 1985 by the Philadelphia Eagles. Two years later after playing golf at Spanish Trail Country Club, Cameron asked Cunningham to say the prayer Christians believe brings nonbelievers into the faith.

Even after saying the prayer, though, Cunningham said he still "didn't understand what it meant to be a Christian" and became caught up in his new-found fame as the Eagles' young star quarterback. He couldn't walk into a Philadelphia mall without being swamped by fans, and his face was on billboards throughout the city. Cunningham told Sports Illustrated in 1988 he considered himself "an impact player" in the same league with Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson and Wayne Gretzky.

"You get selfish, and you get self-oriented," Cunningham said recently about those days.

Despite all the adulation, he also felt alone in many ways, a feeling that haunted him for years. After cancer took his mother in November 1981, and a heart attack claimed his father a year later, Cunningham became afraid to get too close to people.

Later in Philadelphia, some friends backed away after Cunningham declared he had become a Christian. What really ate at Cunningham more than losing friendships was how much he yearned to share his life with someone.

"I was a lonely soul. I needed a wife," he said. "I felt empty and unfulfilled."

He wasn't, however, willing to settle.

Cunningham called off an engagement in 1988 because he didn't believe he was ready to get married. He didn't have trouble finding dates, but would not live the stereotypical professional athlete's life of going from woman to woman.

His soulmate search ended in 1990 at New York's Radio City Music Hall, where Cunningham was appearing as part of a Night of 100 Stars event. He met Felicity de Jager, a ballet dancer from South Africa.

"I didn't know anything about football," she said.

They first became friends, but the spark had been set. Eventually, they began to date and were married in May 1993. The Cunninghams had little idea of what lay ahead: becoming parents to four children and eventually leaders of a young, growing church.

"When we got married, he was in his career and I was in my career," Felicity said. Running a church "was never anything that I desired."

■ ■ ■

The seeds for Cunningham's future ministry came from many sources, but some were planted in 1996 when he was out of the NFL for a year and met minister Troy Johnson, who taught Cunningham how to pray and share his faith. Cunningham joined the Minnesota Vikings in 1997 and met team chaplain Keith Johnson, who also was the founder of Christian Athletes United for Spiritual Empowerment. The Cunninghams even joined the board at CAUSE.

During that time, he also was attending Calvary Chapel Spring Valley in Las Vegas and got to know the Rev. John Michaels. Cunningham began conducting Bible studies first in his home and then in a recording studio he owned at the time, attracting 20 to 30 people at first and then growing the studies to 50 to 60.

"It was really word-of-mouth," said Mike Bussey, who began attending the Bible study in 2003. "We didn't advertise at all."

Michaels noticed, too, and recognized Cunningham's ability to teach from the Bible, and urged the former quarterback to think about starting a church.

"Your Bible study is not a Bible study, it's a church," Michaels told Cunningham. "You have 50 people there. That's almost the average size of a church."

Cunningham, however, was content to run a Bible study and not take on the responsibilities and headaches of heading a church. So he avoided the subject for two years until Michaels brought up the idea again in 2004. This time, Cunningham sensed he should listen.

"I'm like a military person," Cunningham said. "If my leader tells me to do something and I pray about it and if I know it's what God wants me to do, I'll do it."

Cunningham was ordained in March 2004, which is like getting a license to preach, and later that year opened Remnant Ministries in a temporary facility before moving to Silverado High School, where up to 130 attended.

In 2007, the church moved into its current building, a 555-seat structure. Now about 500 attend the Sunday service at 10:45 a.m. and 200 to 250 the one at 8:45 a.m. Including about 250 children for three sets of Sunday school classes, about 1,000 people show up each week.

A wall was taken out to make extra room for the Sunday school classes and a nursery, and the church's growth has prompted Cunningham to add a third service, probably after the summer.

"When we first moved into the building, it seemed huge," said Bill Shoemaker, who has attended the church for more than four years and is responsible for the multimedia department. "But it's getting smaller and smaller."

Many come to see Cunningham because they remember his football feats. He still owns UNLV's all-time passing record with 8,020 yards as well as the school mark with a 45.6-yard career punting average. In his NFL career, which ended in 2001, he passed for 29,979 yards and rushed for 4,928 yards, a league record for quarterbacks. Cunningham, a four-time Pro Bowl player, has been credited for making quarterback a more mobile position.

That stature would be an obvious magnet for the curious to give the church a try, but Remnant's growth would not occur if it was simply a chance to see a preacher who was a famous player.

"I don't even think about his football background," Shoemaker said.

Stacey Jackson, who began attending Remnant about three years ago, said she didn't know it was Cunningham's church when she walked in.

She was searching for a new direction in her life after "hanging out with the wrong crowd" helped lead her to not "care about living." Cunningham invited Jackson into his office to talk about those challenges, and she soon became a devoted churchgoer.

Cunningham also visits with the congregation after each service, and will pray, laugh and even cry with them.

He opens up his nearby five-bedroom, nearly 7,000-square-foot home after Sunday's second service when he performs baptisms in the backyard hot tub. It's almost unheard of for a former athlete with a career as well-known and well-compensated as Cunningham's.

"I'm no one special," he said. "My home, we're grateful that we have it. If I can share my home with someone, maybe that'll make the difference in them having Christ."

■ ■ ■

Cunningham begins putting together his sermon on Sunday night and works on it throughout the week.

He arrives at the church at 6:30 a.m. every Sunday and studies for a half-hour before walking downstairs to pray with "the worship team" -- the singers and musicians. Cunningham then returns to refine the sermon, and he tweaks it between services.

He plays percussion in the band before delivering the type of sermon that follows his personality of being low key, serious and determined. Cunningham sprinkles football references to make larger points, and explores sections of the Bible in an easy-to-understand way.

"Maybe the Rhodes Scholar doesn't want to go to church here," he said.

Though Cunningham's sermons usually focus on specific verses, he will discuss topics, and on the day of the Super Bowl talked about the importance of accountability.

"We need somebody to hold us accountable on a daily basis," Cunningham preaches. "Everybody needs to be held accountable, including me."

Cunningham later said he consults with six pastors, who guide him when questions arise. To the church, he tells congregants that accountability has practical uses such as not taking an extra 15 minutes for lunch and being careful about the words that are spoken.

It could sound like a self-help seminar, but Cunningham reminds his audience "being accountable begins with God."

"People that don't want to be accountable," he says, "have something to hide."

His ministry isn't confined to the church. He coaches youth football and track, and is the offensive coordinator on Silverado's football team.

Because he doesn't want to violate the separation of church and state, Cunningham said he doesn't walk in preaching to the athletes. But he will answer questions when athletes ask him about being a pastor, and Cunningham tells players who curse that "there's a better choice of words."

"I don't throw the Gospel down people's throats," Cunningham said. "I live it. I share it."

He also shares his cell phone number, and it is dialed throughout the day by members of the congregation. Some call to talk about a difficult situation such as a family crisis, but others call with news about what they see as God's work in their lives.

Spending time with his athletic teams and those in the church often takes Cunningham away from the actual building. He is at Remnant about three days per week but said, "If it was a 9-to-5 job, you wouldn't get out and evangelize."

■ ■ ■

Whites and Hispanics are a part of the mostly black congregation at Remnant, and Cunningham said he's pleased the church is welcoming to diverse families and backgrounds.

The church's growth rate led him to begin what he calls the "Arise & Build" campaign to raise money in hopes of breaking ground in three years on a $10.5 million, 50,000-square-foot facility that will be three times larger than the current building. Cunningham said close to $1 million in pledges have come in.

Raising money is not easy during rocky economic times, and Cunningham knows of a couple who left for another church because of this project.

"It's so funny, they went to another church that's doing the exact same thing," he said. "But when the two left, God brought 20."

Even so, Cunningham said the most difficult part of his ministry is when anyone decides to leave because of the emotional investment made in establishing a relationship. But as evidenced by the church's growth, Cunningham pointed out, "We haven't had a lot of people leave."

So he plans for the new building while preaching to and leading those who enter the current sanctuary.

While preaching, Cunningham tries to build up the listeners while expressing the importance of living "lives so you're right by God."

And in leading, Cunningham knows it's best to lead by example.

"I don't cheat on my wife," he said. "I don't drink. I don't curse. I don't condemn people. I don't tear people down from the pulpit."

Contact reporter Mark Anderson at manderson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2914.

Slide show: Randall Cunningham

Video: Randall Cunningham