Rebels’ runback still resonates

The UNLV-Baylor video from 1999 has become a teaching tool for Rebels cornerbacks coach Mike Bradeson.

In it, UNLV linebacker Tyler Brickell and cornerback Kevin Thomas are seen doing what they were taught in practice. Brickell swipes at the ball to knock it loose, and Thomas sprints from the far side of the end zone to grab the ball and bolt down the field.

"This is why, it doesn't matter when, you run to the ball," Bradeson said. "The game should have been over."

Today -- yes, Sept. 11 -- is the 10-year anniversary of the most unlikely play in UNLV football history and one of the craziest ever in college football. It's the day the Rebels stunned Baylor with a 100-yard fumble return in the last second for a 27-24 victory before a silenced crowd in Waco, Texas.

THE SITUATION

It was only John Robinson's second game as UNLV's coach and the second one for coach Kevin Steele at Baylor.

Nine days earlier in a 26-3 victory at North Texas, UNLV ended a 16-game losing streak and 26-game road skid.

Steele was facing similar issues. Coming off consecutive 2-9 seasons, the Bears had lost the week before at Boston College 30-29 on a missed extra point in overtime.

Wanting to establish a more aggressive and confident mindset, Steele saw an opportunity in the closing seconds against UNLV.

Leading 24-21, Baylor had gained a first down to the Rebels' 8-yard line with 28 seconds to play. UNLV had no timeouts remaining, so Baylor quarterback Jermaine Alfred only had to drop to a knee and the congratulatory handshakes would have begun.

"When you have the chance to ice the game, you ice it," Robinson said. "You can't let some agenda get in the way."

But Steele did, instructing his players to try to score a touchdown. UNLV players were furious when they saw the Bears go into a huddle, and they knew they couldn't allow Baylor to score.

"I was kind of pissed that they're trying to ram it down our throat," Bradeson said.

THE PLAY

The Bears didn't try anything fancy. As the clock dwindled to 8 seconds, tailback Darrell Bush took the handoff and charged between the tackles.

"If he got to the end zone, we wanted everybody to hit the guy," Thomas said. "It was not right."

UNLV cornerback Andre Hilliard and safety Quincy Sanders met Bush at the 3 and held him up, desperate to keep the churning tailback from reaching the end zone.

"I thought we had lost," linebacker Brickell said. "A couple of plays earlier, I almost stripped the guy of the ball, so I thought if I can, I'll do it again when I get the opportunity."

As Bush reached for the end zone, Brickell charged from his left side and knocked the ball loose and it bounced a yard deep into the end zone.

Thomas sprinted from the other side and grabbed the ball about a foot above the ground. He only had to get past Baylor's 251-pound fullback Melvin Barnett.

"As soon as I picked up the ball, I knew I was going all the way," Thomas said. "I got it in my hands and looked up and outran (Barnett). I just didn't know if there was a penalty. I had a clear path."

Up in the coaches' box, Bradeson had just removed his headset and stood up to get ready to go downstairs. But when he saw Thomas running down the left sideline, he grabbed a microphone and yelled, "We're going to win! We're going to win!"

THE AFTERMATH

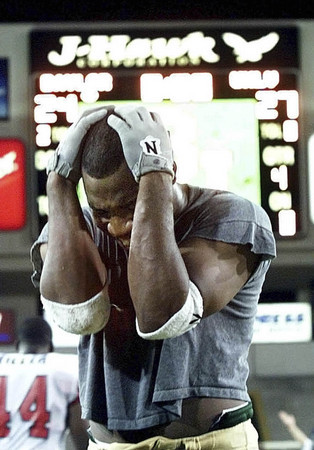

The sudden and total silence of Baylor fans stays with Thomas. Robinson walked over to shake hands with Steele, who looked as if the life had left his body.

The play made national news, but because the game wasn't televised, it failed to take a greater hold on the public imagination. ESPN.com ranked it No. 85 among college football's defining plays. Scout.com ranked it the 48th greatest finish.

Ten years later, though, the effect seems to be noticeable for two primary participants.

Steele arguably never recovered from his bold play call. Baylor went 1-10 that year, and after four seasons he was 9-36 and out of a job.

He hasn't been a head coach since. Now defensive coordinator at Clemson, Steele said through a school spokesman the play doesn't seem like it happened 10 years ago. "It seems like 50," he said.

Thomas said the play helped give him confidence that he could be a top player. He became the Mountain West Conference Defensive Player of the Year in 2001 and a sixth-round NFL Draft choice in 2002. Thomas played four seasons with the Buffalo Bills.

"That play actually boosted my whole career," he said. "I don't think I would've gotten as much pub (publicity) later in my career if it wasn't for that play. I think that play established me."

LESSONS LEARNED

Each preseason, Bradeson pulls out the videotape and shows players the importance of following coaching and never giving up.

There's Brickell stripping the ball and Thomas running hard to grab it. Just as they were taught.

"You always practice doing those kind of strips," Brickell said. "The opportunity presented itself and I went for it."

Thomas added, "That's why you always run to the ball. That's the story of the Baylor game."

Steele, of course, learned the hardest lesson.

"I don't think about it much now," Steele said. "It was just a great lesson of football, one of many I have had in my coaching career."

But one decision, no doubt, he would like to have back.

"The game was over if (Baylor) chose it to be over, and they tried to run an additional play," Robinson said. "That should be the film clip for every coach to remind you not to screw it up."

Contact reporter Mark Anderson at manderson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2914. Read the latest UNLV football updates at lvrj.com/blogs/unlv_sports.