Bill to keep Nevada public employee retirement records secret was always a bad idea

Senate Bill 384 has been many things in its short life, but it has never been a good idea.

Written in reaction to multiple court rulings which held — reasonably — that public employees’ pay and retirement benefits should be open to inspection by the public, SB 384 sought to do by legislation what the Public Employees Retirement System couldn’t do by litigation: drop a veil of secrecy over at least some records.

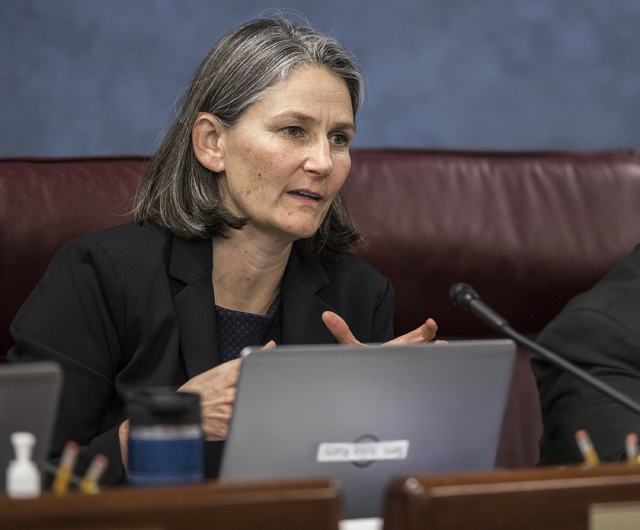

The initial version of the bill, introduced by Sparks Democratic state Sen. Julia Ratti in March, would have provided that the name, employer, position and annual salary of a public employee were public, but everything else in that employee’s file was confidential. It would also have said that the name, last public employer and amount of annual pension benefit of a retired public employee, retired judge or state lawmaker would be public, but everything else confidential.

But that version of the bill lasted only a month, before a pernicious amendment in the Senate’s Government Affairs Committee in April. The amended version said names of retired public employees would be confidential, but that an identifying number, the last public employer, the number of years in public service, the retirement date and amount of annual pension benefit would be public.

The reason? Advocates said the bill would fight identity theft targeting older, retirees. And anyway, there’s no reason to reveal a person’s name because the identifying number is good enough. (Full disclosure: My wife is a public employee and participates in PERS.)

Recall, again, that we’re talking about people who worked for you, the taxpayers, were paid with your tax money, whose retirement includes contributions from public agencies, which is overseen by a public board. There’s virtually no part of these records that should be private. (And the inclusion of members of the Legislature — elected representatives of the public — is especially rich.)

That version of the bill was approved on a near party-line vote in the state, 11-10, with Sen. Nicole Cannizzaro, D-Las Vegas, joining minority Republicans in opposition.

The bill drew the expected objections from journalists and the Nevada Policy Research Institute, a conservative group that also had to sue PERS to get access to information that it posts on its website, Transparent Nevada. (Those lawsuits, by the way, were fought with your tax dollars, too, and the litigation was protracted by the transparently nefarious acts of PERS.)

The bill moved through the Assembly’s Government Affairs Committee, all the way to engrossment in the general file, where it awaited a final vote of approval before being sent to Gov. Brian Sandoval.

But instead of passing the bill, the Democratically controlled Assembly placed it on the chief clerk’s desk, a sort of legislative limbo for bills that have some defect or political problem awaiting correction.

And last week, the Assembly amended the bill once again, this time to specify that the name, the last public employer and the amount of annual pension benefit are public, but — bizarrely — the number of years of service and the retirement date must be confidential.

Why — if identity theft was the issue — would the bill be amended in this way? It certainly makes sense if the idea is to prevent people from figuring how long a person worked for the pension they’re receiving. And it’s also a bad precedent: declare some information confidential now, so that the rest can more easily be cloaked in secrecy in the future. (This version passed the Assembly Thursday on a party-line vote.)

The bottom line is, none of the information that SB 384 sought to shield should be confidential. That’s what makes the tortured path of this bill so frustratingly pointless. And it’s a good reason for Sandoval to make it his next veto.

Contact Steve Sebelius at SSebelius@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5276. Follow @SteveSebelius on Twitter.