90 years after discovery, weird little Pluto remains controversial

You have to feel for the little fella.

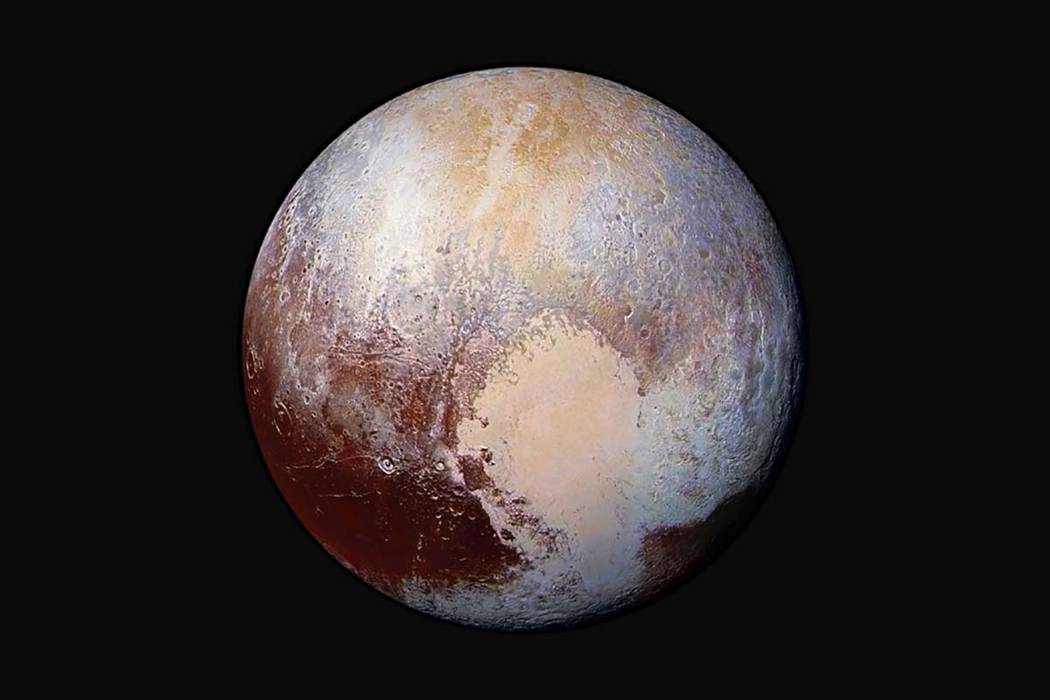

Pluto doesn’t have the bling of Saturn’s rings. It lacks the famed little green men of Mars. It certainly isn’t as much fun to say as Uranus.

It was part of the group, but the general public rarely paid Pluto much attention. Then, on Aug. 24, 2006, it went from being the Ringo of planets to being the Pete Best.

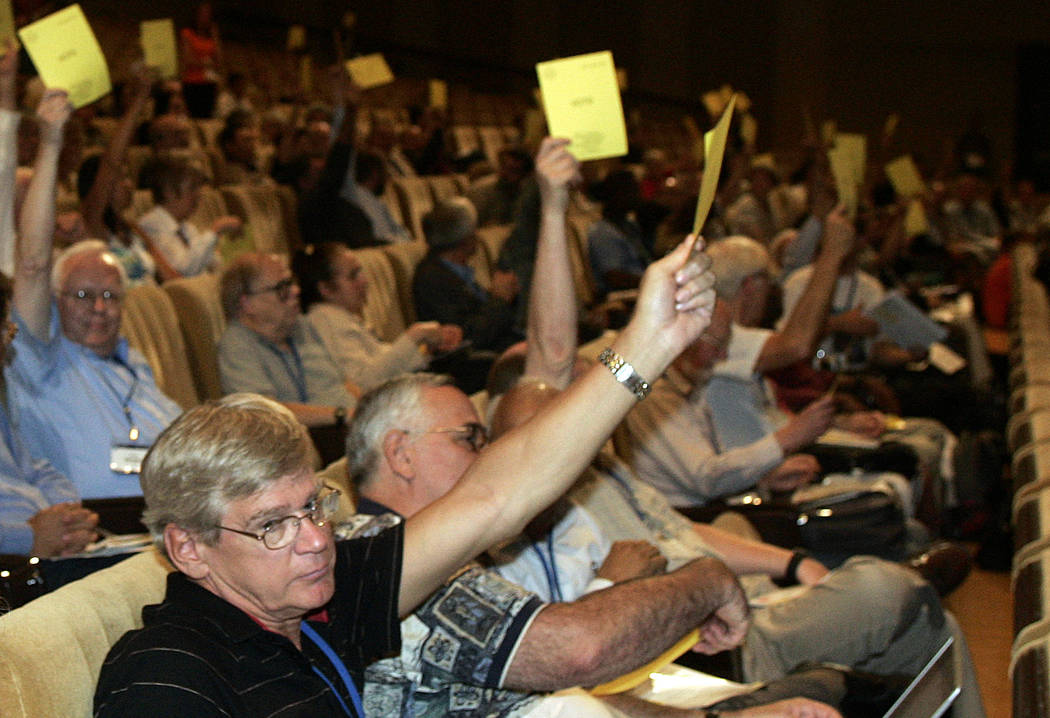

That’s the day the International Astronomical Union took away Pluto’s planethood — because apparently that’s something the organization granted itself the power to do — and confusingly deemed it a “dwarf planet.”

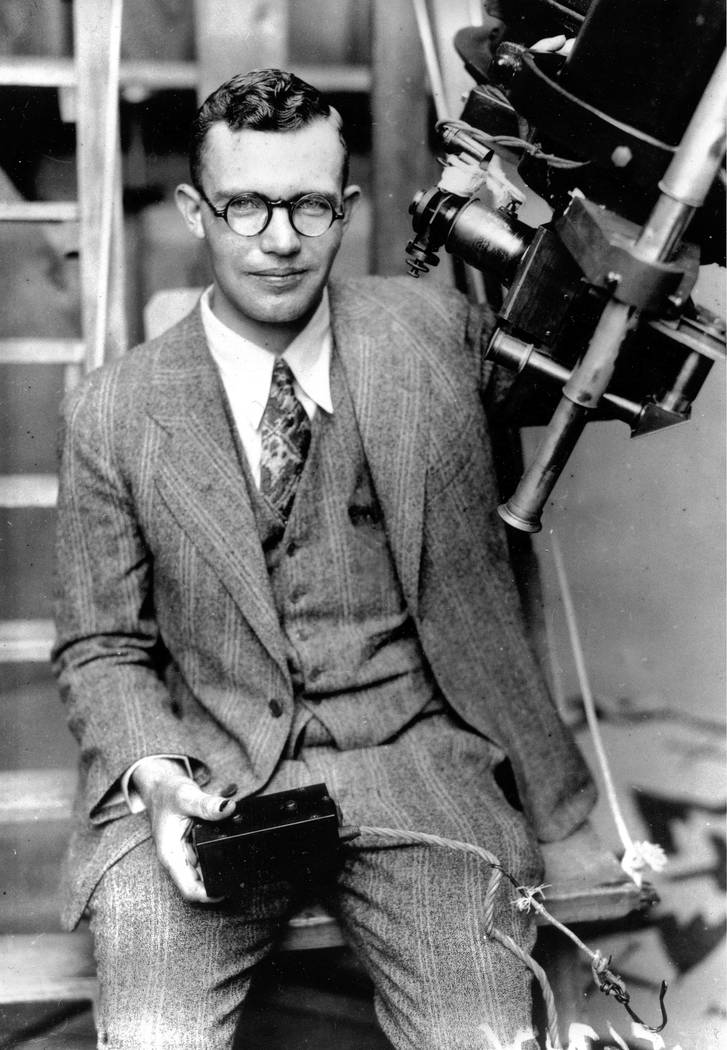

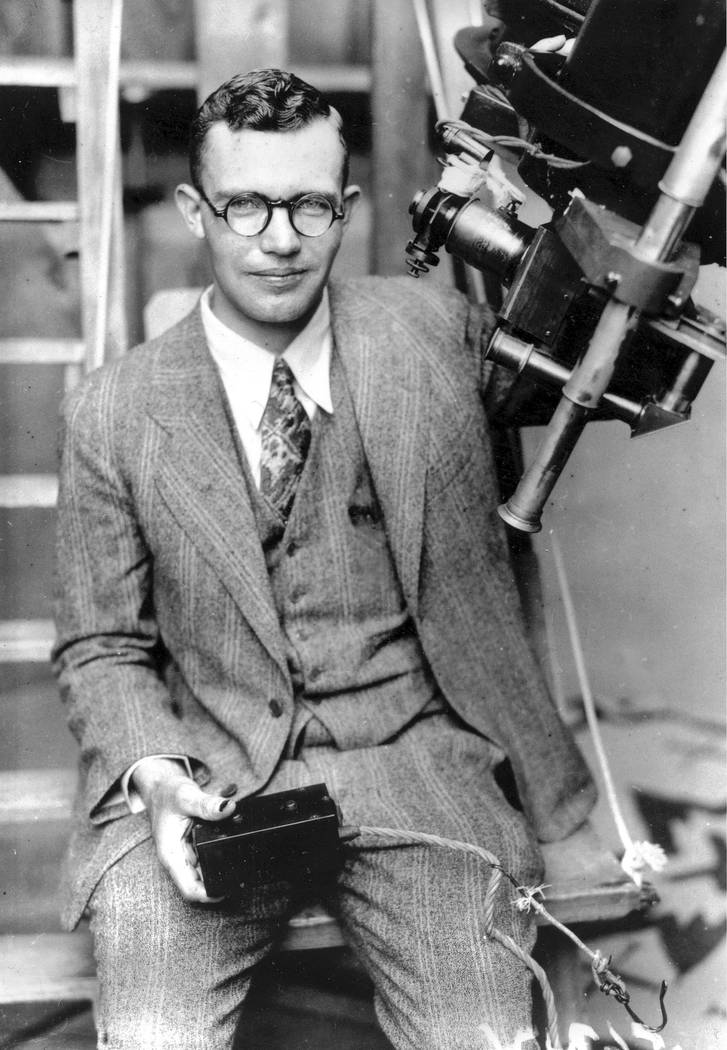

Who could have guessed back on Feb. 18, 1930 — the day it was discovered by 24-year-old self-taught astronomer Clyde Tombaugh at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, some 250 miles from Las Vegas — that Pluto would turn out to be such a troublemaker?

The vote was rigged

“Oh, in my view, it’s totally a planet,” says Andrew Kerr, manager of the College of Southern Nevada’s planetarium, who notes that the second word in “dwarf planet” is, in fact, “planet.”

The biggest problem Kerr has with the status change is the organization’s vague condition that, for something to be a planet, it must have “cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.”

This is clearly a jab at Pluto, which is one of thousands of icy bodies that make up the distant Kuiper Belt. Given the number of asteroids and various objects in the orbital paths of Earth and its neighbors, Kerr says, the IAU standard “is so horrible, there’s not a single planet in our solar system based on their definition.”

In an effort to leave nothing to chance, Kerr says, an anti-Pluto faction of the IAU waited to call the controversial vote until the end of a global conference in Prague. By that time, most of the planetary scientists, Pluto’s staunchest defenders, had gone home.

“The reality is, when they did that, they actually rigged the vote. … It wasn’t exactly done on the up and up.”

In the end, Pluto’s fate was sealed by just 424 of the approximately 10,000 professional astronomers around the world.

“You’re looking at the beginnings of troll culture with the internet,” Kerr says of the era when that vote was cast. “Part of me just wonders if some of them weren’t just trying to troll their friends a little bit.”

It’s a strange one

Pluto seems an odd candidate to elicit strong emotions of any kind.

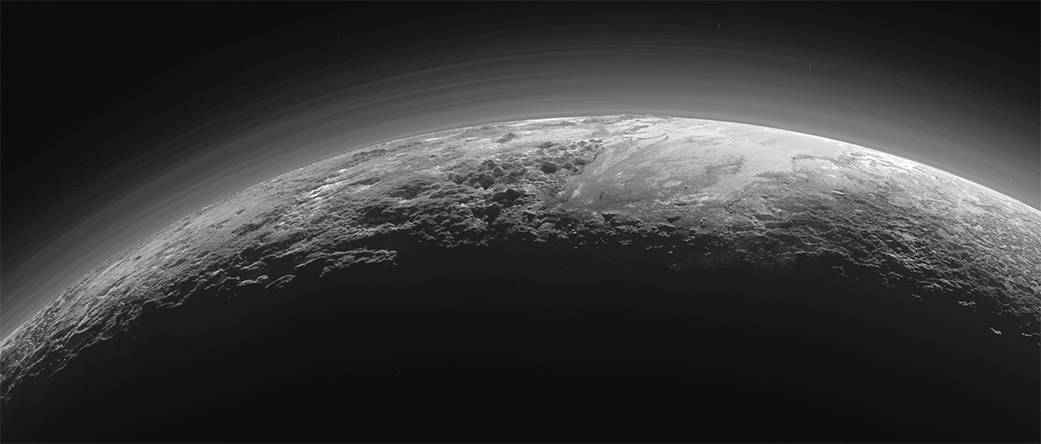

A year on Pluto is the equivalent of 248 Earth years, thanks to its tilted, elliptical orbit — another thing separating it from the eight commonly agreed upon planets — that sometimes brings it closer to the sun than Neptune.

Stay in your lane, Pluto!

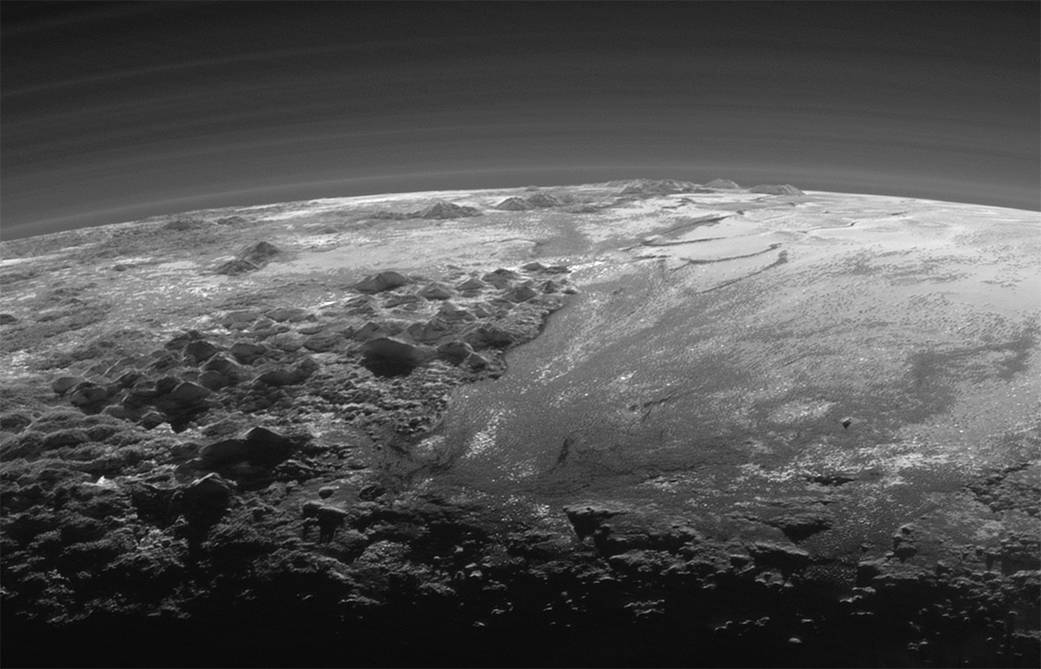

It’s almost impossibly small — just 1,400 miles, or about half the width of the United States, across. Surface temperatures can drop to as low as minus 400 degrees Fahrenheit. And a big chunk of Pluto is covered by nitrogen-rich ice that evaporates to briefly form an atmosphere before essentially snowing back to the surface and starting the process all over again.

What a weirdo.

Throwing shade

Jason Steffen, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at UNLV, doesn’t want to pat himself on the back, although he’s been a proud Pluto denier for decades.

“The IAU arrived at the conclusion that I had arrived at, I don’t know, 20 years earlier,” he says.

Steffen has been a member of the science team for NASA’s Kepler mission, which, according to the agency, discovered more than 2,600 planets outside our solar system. In his mind, Pluto has more in common with an asteroid than a planet, and the reclassification is simply correcting a longstanding mistake.

Having Pluto as the ninth planet, Steffen says, was “a gigantic piece of historical baggage that we were stuck with until there was clear observational motivation to put it back where it belonged.”

By his rationale, there are only eight planets in our solar system, and, despite their name, dwarf planets are not planets.

Also not planets, based on this

criteria: Planet Hollywood,

Planet Fitness and travel publisher Lonely Planet.

Still, Steffen insists, he never felt any ill will toward Pluto, although he’s been known to throw a little shade its way.

“I would say mean comments about Pluto and talk behind its back in my astronomy class,” he says, “but it’s not like it really bothered me.”

‘Show your love’

Lowell Observatory, which bills itself as “the home of Pluto,” is hosting the I Heart Pluto Festival on Saturday and Tuesday to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the discovery. It’s inviting visitors to drink Pluto Porter beer, eat Pluto-themed sushi rolls and “come show your love for our frosty ninth planet.”

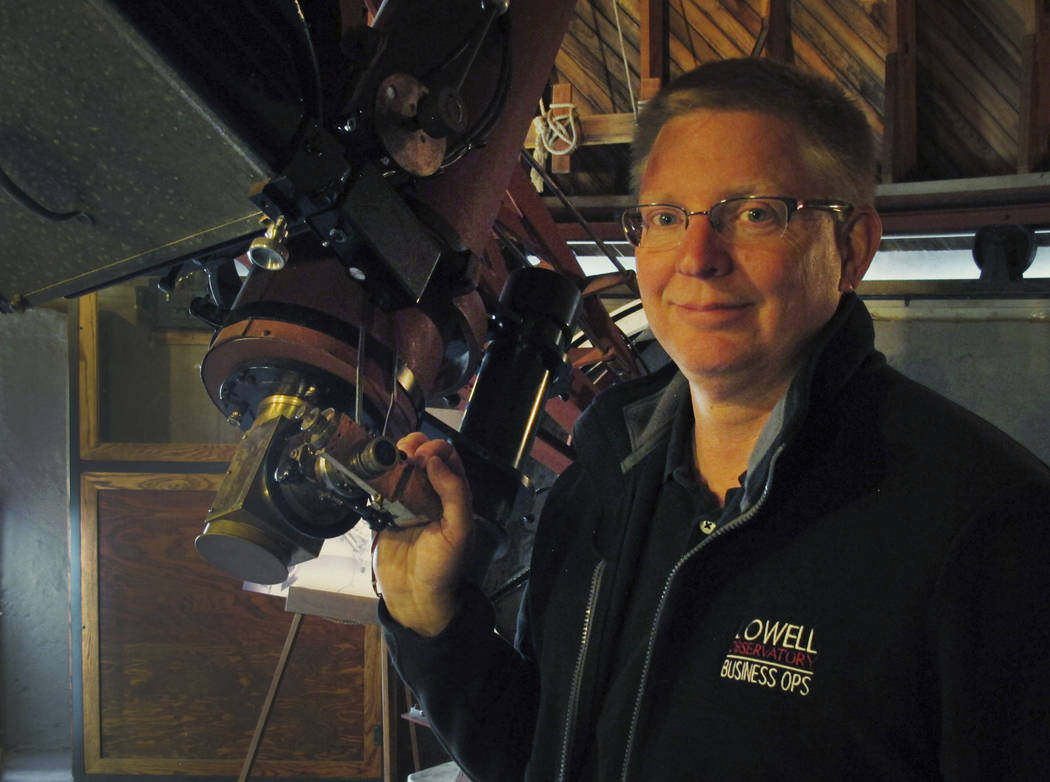

“As an observatory, we don’t necessarily have a stated take on it,” Lowell historian Kevin Schindler says of the controversy, “but most people at the observatory consider it a planet. I wouldn’t say everybody.”

There are no Team Planet vs. Team Not a Planet cliques, he says, and no scientists are shunned at lunch because of their Pluto-related beliefs.

“Most of our astronomers aren’t really outspoken about it and, in a lot of ways, don’t care what it’s called,” Schindler admits.

The important thing is that Pluto, however you think of it, was discovered at Lowell, and that connection helped attract 110,000 visitors last year.

In reality, Schindler says, even though the observatory had to update its tours, the change wasn’t that big of a deal.

“There’s this feeling that the planets are the great all-powerful planets and everything else sucks. Like there’s a hierarchy,” he concludes. “But there’s not. It’s just different classifications.”

Contact Christopher Lawrence at clawrence@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4567. Follow @life_onthecouch on Twitter.

Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, is inviting Pluto fans to celebrate the 90th anniversary of its most famous discovery.

The I Heart Pluto Festival, scheduled for Saturday and Monday, will include special tours, lectures and the rededication of the Zeiss Blink Comparator that Clyde Tombaugh used to discover Pluto in 1930.

For more information, see iheartpluto.org.