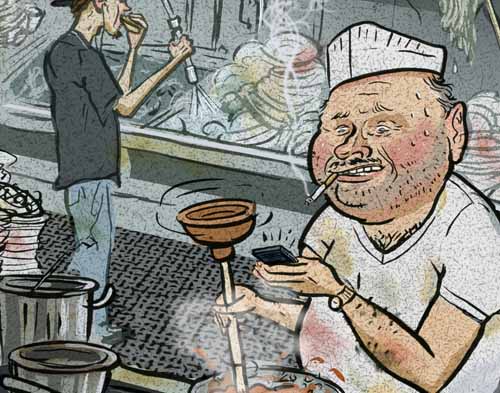

Restaurant inspections protect the public

If you've ever wondered how restaurants earn those B's, C's and closures that land them in the Restaurant Report in each Wednesday's Taste section -- and, more to the point, how other restaurants earn the A's that keep them out of the newspaper -- here's a primer, courtesy of Gregg Wears and Carol Culbert.

Wears is an environmental health supervisor for the Southern Nevada Health District, Culbert a senior environmental health specialist. That puts them on the front lines of the ongoing battle against foodborne illness, commonly called food poisoning or any of several less-publishable names. Foodborne illness is the reason restaurants are inspected -- to ensure that they're safe for customers to eat there.

First, a bit of information about foodborne illness. Depending on the pathogen involved, the incubation periods -- the period between exposure and the onset of symptoms -- can vary greatly, from as little as one hour to as long as 14 days. That means that while you're absolutely, positively, God-fearingly certain that the diarrhea you suffered through last night was caused by the burrito you ate yesterday afternoon, the reasonable assessment of that is: maybe. Or maybe not.

It might, instead, be from the salad you had at that haute cuisine spot last week.

"Or perhaps from their own home," Wears said. "It can be self-inflicted." And without extensive testing -- which tends to be rare, because of expense, logistics and usefulness of the information -- the source will remain uncertain. But you can call the health district and report it (although statistics on how many people report their own kitchens remain elusive). Or, should you seek medical attention, your physician can call and report it.

Which doesn't mean a witch hunt ensues.

"Our epidemiology people have a history that they take from people calling in a complaint," Wears said. "They use that to eliminate places where it most likely didn't happen, or to identify places that need to be investigated. If we're getting three or four or five reports on the same place, that's kind of a flag to go there."

That's not the only flag to go there. Each restaurant permit issued by the district comes with at least one inspection a year, so many of them are done on a purely routine basis. Inspectors, Wears said, are assigned to specific properties and/or geographic areas.

Upon entering a restaurant or other food-service facility, Wears said, the inspector announces himself or herself and asks for the person in charge.

"For the most part, it's not a combative relationship," Wears said. "Certainly, we have facilities that are pleased to see us; they know they do well, they know we recognize that. That's a very positive relationship.

"Others know that they are not doing so well. They might not be happy to see us, but they know, generally speaking, that they have a responsibility to let us in."

The inspector interviews the manager on duty. In a recent addition to the process, the manager is questioned about food-safety knowledge, such as the symptoms of employee illness -- the sort of things, such as diarrhea or fever, that would indicate the employee should not be handling food.

"We want to know if they encounter that, or their employees report those illnesses, that the person in charge knows they're supposed to go home or seek treatment." Wears said there can be a tendency for employees to work through illness to keep paychecks coming, or for an employer to encourage it to maintain staffing levels.

"Let's do food safety, not think about money here," he said. "That's part of that rationale."

Then, whether accompanied or not by the manager on duty -- which makes no difference to the inspector, Wears said -- the inspector begins to make his or her rounds. While the points of inspection are consistent, Wears said each inspector has his or her own methodology. He likes to move in a right-hand circle to ensure he doesn't skip any spots. He also likes to wash his hands at every sink to test the supply -- and frequency of use -- of hot water, soap and towels.

Health cards are checked, and people who don't have a valid one have to leave work until they do. Cooling equipment is checked to ensure it's in the range of 40 degrees or less. Food is checked to ensure it's in the proper temperature range.

And throughout, the inspector is observing, and talking to employees.

"If somebody's working with food, what's the story of this food that I see in front of me?" Wears said. "Why is it out now? Are you working with it now?

"If you've got a pile of food on the table and half of it is in temperature and half of it's out, you ask questions. You interview the staff that's in front of you, or the person in charge."

They look for sanitizer buckets with wiping cloths, and whether they're being used. They examine equipment for signs of old food debris. If there's debris on a meat grinder, for example, and the employee says it was from the night before, "they wrote their own violation."

"We try to use common sense and the information they give us," Wears said. "It's a deduction based on experience, training, evidence -- not a conclusion that we jump to."

Inspectors watch for signs of cross-contamination -- if, for example, a worker doesn't clean a cutting board between putting away the chicken and taking out the roast beef. They check to see if food in the freezer is frozen; if the employee says it just came in, they'll ask to see the dated invoice.

They check storerooms to ensure syrups or liquids aren't dribbling onto crackers or flour, if bulk containers are properly labeled, that no chemicals or possibly contaminating mechanical items are stored near the food, that personal items are not commingled with the food. If they see insect or animal traps or bait, they'll ask about pest control.

Through it all, they take pictures to document problems. When the inspection is finished, the inspector will complete his or her report and review it with the manager on duty. If a B or C grade is earned, or a closure is enacted, the owner or manager must arrange for a reinspection. If he or she doesn't arrange one within 15 days, the inspector can return unannounced.

Culbert noted that inspections are done during business hours -- not when a restaurant is closed -- and that operational hours can delay a reinspection.

Reinspections after a B grade are free; there are fees for reinspections after a C grade or closing.

How long a restaurant must maintain a lower grade depends on several variables. If, for example, the violations can be remedied on the spot, and the inspector is still in the area, he or she may return the same day -- although the restaurant still will get the lower grade, plus the A to reflect the remedial work. This may be especially true in the case of large properties, such as casinos, that have multiple permits, because the inspector may be there for hours, inspecting the various areas.

Which brings us to another question: Why do some restaurants have more than one permit? Square footage and seating are factors, Wear said, but not the only ones.

"The way we look at that is by identifiable area, function or geography," he said. "We can have a casino the size of MGM Grand, and if we say, 'OK, all of your kitchens are on one permit, and we went in and did it, we couldn't possibly do all of those kitchens and not get more than 10 points" in demerits, which would trigger a B.

"But those kitchens have different functions," he continued. "So we give them different permits to identify a functional area or a geographical area."

As to why so many small ethnic restaurants tend to appear in Restaurant Report, Wears said it often is a function of culture, education, training or economic circumstances.

"Not all ethnic operators are like that," he noted. "There are some that are highly skilled and highly trained."

Despite all they've seen, Wears and Culbert do continue to go out to eat.

"There are places I like to go to," Culbert said. "I won't frequent a place that has a history."

"We also know to look at the grade going in," Wears said.

Still ...

"I, like probably every other person in town, have my favorite places because I like the food, I like the service and I like the people," he said.

"And pretty much whatever they have -- unless it's really, really bad -- that's where I'm going to go."

Contact reporter Heidi Knapp Rinella at hrinella@review journal.com or 702-383-0474.

DO RESEARCH

Southern Nevada Health District restaurant inspections, dating back to 2005, can be viewed on the district's website

SouthernNevada HealthDistrict.org.