WrestleMania in Las Vegas: Evil clowns, exotic animals and The Undertaker’s worst match

Google “worst WrestleMania,” and if the ninth installment of professional wrestling’s biggest show isn’t at the top of the list, it’s a consistent top three.

Of the six photos on the cover of the book “Wrestlecrap: The Very Worst of Pro Wrestling,” half are from that afternoon, April 4, 1993, at Caesars Palace.

One matchup involved identical evil clowns. Hulk Hogan left with the top title despite never really being in a match for it. Of the nine bouts, only two had clean finishes that didn’t involve some form of cheating — and one of those lasted less than four minutes.

Talking about that day, 30 years after the fact, is enough to give The Undertaker chills.

“I was so consumed with my contribution to (the) awfulness,” says Mark Calaway, who had arguably the worst match of his three-decade in-ring career as The Undertaker. “I don’t really even look back anymore at it. I’m just like, ‘Wow, that was a real bump in the road that day.’ ”

Reminded of some of the famously divisive events of that afternoon, his fellow WWE Hall of Famer Shawn Michaels is more succinct: “Oof.”

The whole thing was a bit of a mess, especially by modern WrestleMania standards.

But it was our mess.

Cranking up the hype machine

Both the World Wrestling Federation, as it was known back then, and Las Vegas were going through major transitions in 1993.

Business was suffering as some of the biggest stars in the WWF were leaving the company faster than new ones could be made. In the previous 12 months, household names including the Ultimate Warrior, Ric Flair and Roddy Piper had left the company. Hogan was about to have his first match in a year, and Randy Savage had been relegated to the announcers’ table.

On the Strip, The Mirage reignited the long-dormant theming trend when it opened in November 1989. The medieval fantasy of Excalibur came online the following summer, and the heavily themed Luxor, Treasure Island and MGM Grand were preparing to open later in 1993.

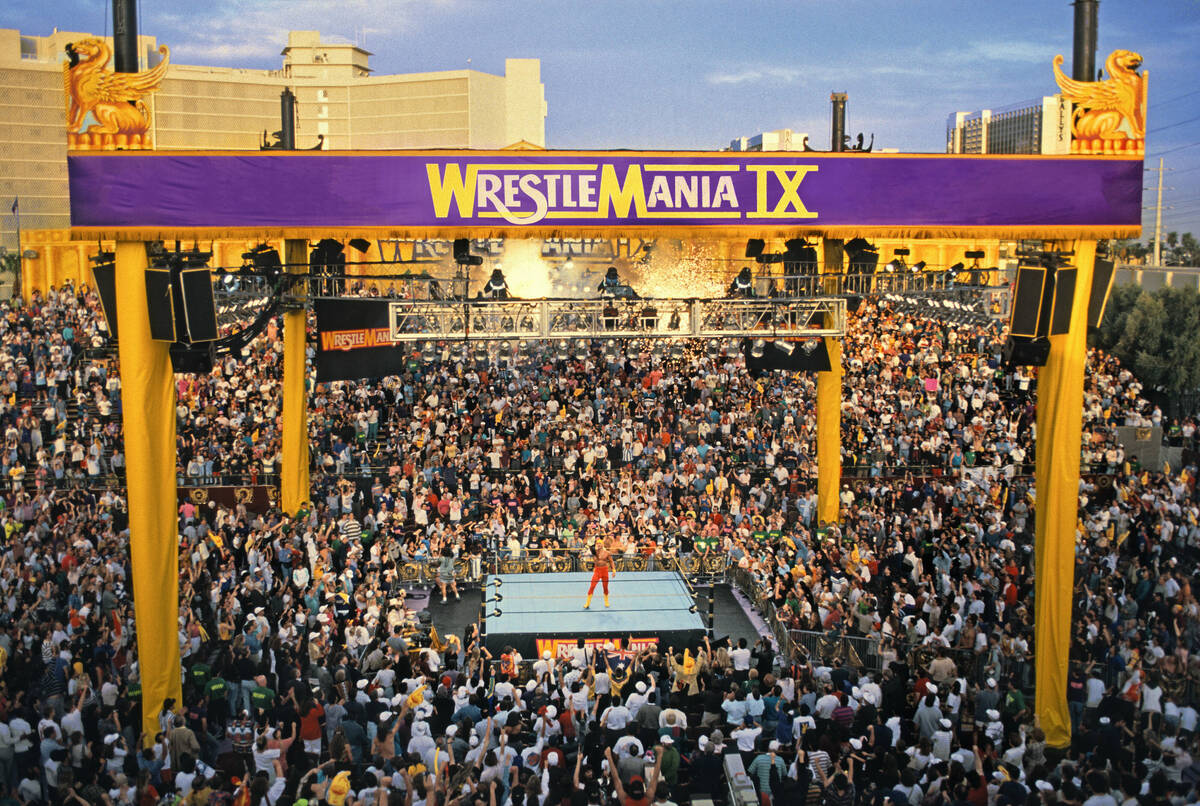

The WWF was looking for a different vibe for its annual “Showcase of the Immortals” after 62,000 people attended the previous WrestleMania in the Hoosier Dome in Indianapolis. Caesars, which had a 16,000-seat outdoor setup that was about as different as vibes get, was leaning into its Roman Empire theming and seeking some exposure.

Boy, did they get it.

The hotel’s Julius Caesar and Cleopatra were given a prime spot just before the main event during that January’s Royal Rumble. “Las Vegas, Nevada, rapidly becoming the family entertainment capital of the world,” announcer Gorilla Monsoon declared as the duo approached the ring.

Caesar then read a proclamation inviting the confused and indifferent Sacramento crowd, as well as those watching at home, to WrestleMania IX at “the sumptuous, splendiferous, lavish home of the champions, Caesars Palace.” It was, he promised, a domain “where your every whim is waiting to be satisfied, where your desires will be fulfilled.”

That was surely one of the few times some of those words had been uttered inside a wrestling ring.

By the time WrestleMania IX drew near, the WWF hype machine was firing on all cylinders.

Monsoon and Bobby “The Brain” Heenan hosted that week’s “Prime Time Wrestling” from the Caesars Palace pool.

That week’s “WWF Superstars” had owner Vince McMahon, Jerry “The King” Lawler and Savage hosting from in front of the resort’s fountains and reflecting pools, the Fountain of the Gods and the animatronic Bacchus statue in the old Festival Fountain.

“Gentlemen, feel like spending a little money over in the Forum Shops here at Caesars Palace?” and “ ‘Macho Man’ Randy Savage, can you believe the shops around here?” were things actually said by McMahon on national television.

‘A ton of interest’

That first weekend in April was a massive one for Las Vegas sports.

Canyon Gate hosted an LPGA tournament, while the city’s inaugural Big League Weekend featured a series of exhibition games involving the Brewers, Cubs, Mariners, Padres, White Sox and the Las Vegas Stars that brought the likes of Ken Griffey Jr., Bo Jackson and Harry Carey to Cashman Field.

Most of the talk, though, was about WrestleMania and its first, and so far only, time in Las Vegas. Tickets were priced from $25 to $150. By comparison, the face value of the best seats at this weekend’s WrestleMania 39 in L.A.’s SoFi Stadium is $5,000.

“It felt like a ton of interest in it,” says Kevin Iole, the former Review-Journal sportswriter and current MMA and boxing writer for Yahoo Sports, who covered WrestleMania IX for us.

He’d reported on everything from the NHL’s first outdoor game, also at Caesars, to dozens of big-name boxing matches. As for the atmosphere that afternoon, Iole says, “That seemed right up there with any big event that I had covered.”

A trip to ancient Rome

What transpired at the top of the show was a spectacle the likes of which wrestling fans hadn’t witnessed — or seen since.

WWF crews had spent a week transforming the outdoor arena into a Roman colosseum. Not that they had much choice.

“The reality of the situation was, the stadium outside of Caesars was a dump,” Bruce Prichard, executive director of the WWE Creative Writing Team, says of the venue that was little more than bleachers in a parking lot. “I mean, there’s no other way to describe it. It was really a dump. It was a (expletive) hole.”

The theming didn’t stop there.

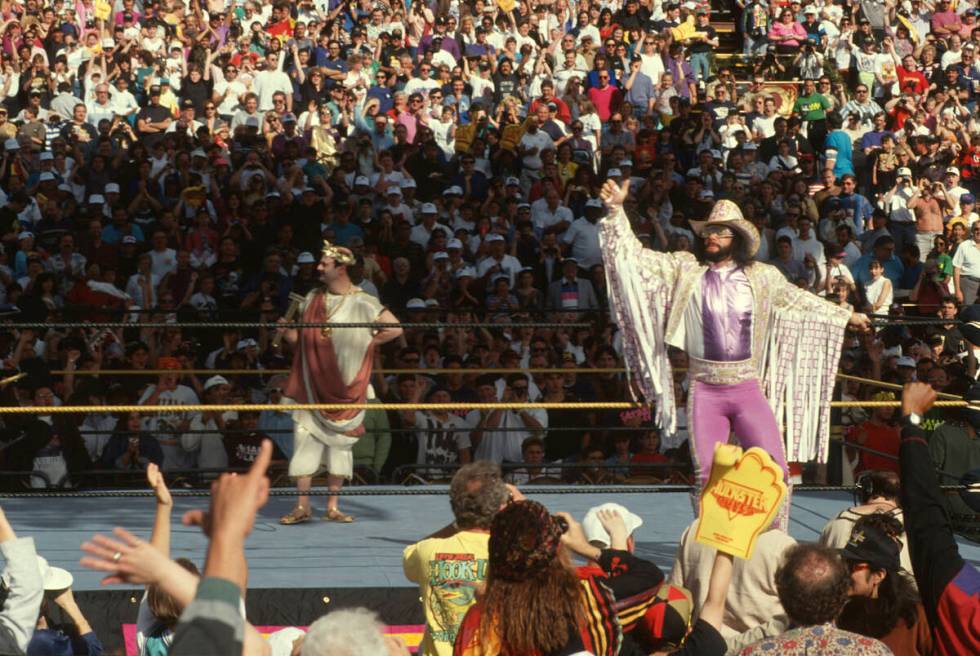

Caesar and Cleopatra rode an elephant to the ring. A llama and an ostrich would follow as part of a parade of dozens of men and women dressed like gladiators, centurions and other members of ancient Roman society.

Cameramen wore tunics, and the announcers sported togas — with the exception of Savage, who was dressed normally, or at least as normally as he ever was. He was carried to the ring on a sedan as Vestal Virgins fed him grapes.

Heenan, meanwhile, arrived at the announcers’ table riding a camel, facing backwards and holding on for dear life before eventually sliding off in a tangled heap.

“Bobby embraced it. Bobby had fun with it. And there was a lot to have fun (with) in that atmosphere. It was just a cool atmosphere,” Prichard says. “Bobby’s a pro. And let me tell you, that camel was a pro, too.”

The downside of wrestling in broad daylight

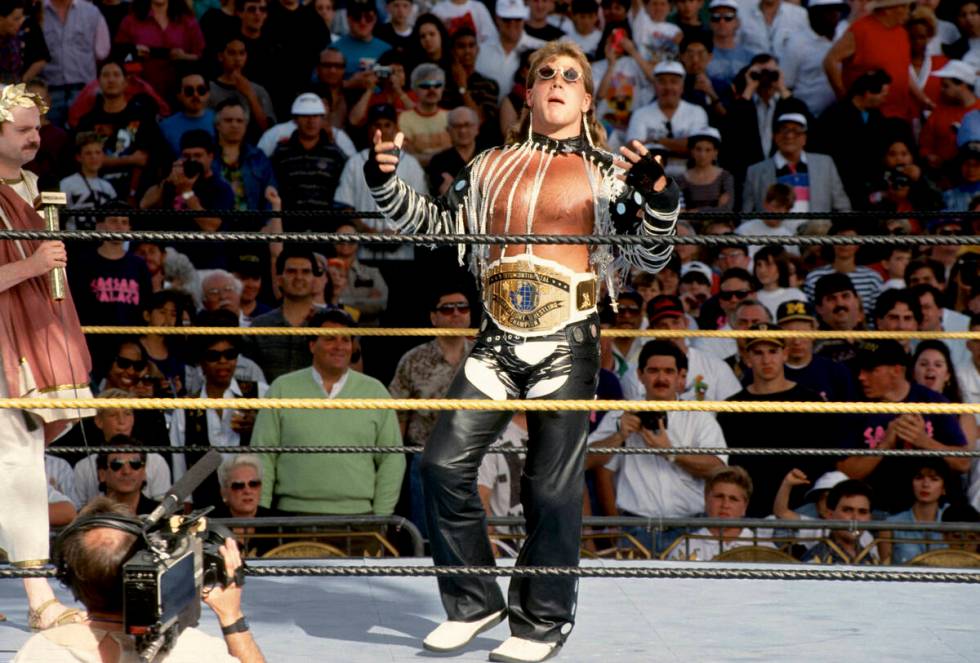

Shawn Michaels may have been the only person on the card with previous experience wrestling at a casino. (WrestleManias IV and V were sponsored by Trump Plaza in Atlantic City, but the matches took place in the nearby Boardwalk Hall.)

His first national exposure came as a 20-year-old, in 1986, during the American Wrestling Association’s tapings for ESPN at the Showboat on Boulder Highway.

“It was just a great time,” Michaels says, calling those days here “just a huge blessing and just the greatest beginning and introduction to a wrestling career a guy could have.

WrestleMania IX card

The following matches took place April 4, 1993, at Caesars Palace:

- El Matador defeated Papa Shango (non-televised)

- Tatanka def. Shawn Michaels

- Rick Steiner and Scott Steiner def. The Headshrinkers (Fatu and Samu)

- Doink def. Crush

- Razor Ramon def. Bob Backlund

- Money Inc. (Irwin R. Schyster and Ted DiBiase) def. The Mega Maniacs (Hulk Hogan and Brutus Beefcake)

- Lex Luger def. Mr. Perfect

- The Undertaker def. Giant Gonzalez

- Yokozuna def. Bret Hart

- Hulk Hogan def. Yokozuna

“But as you know,” he adds with a laugh, “the old Showboat, way different than Caesars Palace.”

Before what would be the first outdoor WrestleMania, and the last for another 15 years, McMahon told Michaels the crowd’s reactions wouldn’t wash over him as they did in an arena. Outside, he said, the sound would travel up, so it would be harder to gauge how fans were responding.

That wasn’t Michaels’ biggest problem that day, though, when he faced the Native American wrestler Tatanka a little after 4 p.m.

“In the day with the sun shining is the part that throws me off the most, because that mood doesn’t feel the same,” he says. “You’re so used to being in the dark, and there’s a comfortability there.”

In other words, it’s harder to perform as a larger-than-life character — especially one like his, nicknamed the Heartbreak Kid, who danced around to a theme song in which he repeatedly sings “I’m just a sexy boy” — when it’s so bright you can see the face of every man, woman and child in the crowd.

Clowning around

It’s difficult to put into words what a delightfully strange time this was in the WWF.

Among those competing in the ring that afternoon was longtime Las Vegan Charles Wright. He’d later be inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame under his pimp persona, The Godfather, but on this day, he was the voodoo-practicing Papa Shango.

The legendary Tito Santana had inexplicably been repackaged as El Matador, complete with the standard bullfighting costume.

Irwin R. Schyster — Get it? IRS? — was a despicable tax collector.

Among the more confusing gimmicks was Brutus “The Barber” Beefcake, an exotic dancer by trade who added a side-job as a hairstylist along the way. Why he always carried garden shears instead of scissors remains a mystery.

Then there was Doink the Clown. A demented circus act, he was feuding with Crush, whose sole gimmick was being large and Hawaiian.

That afternoon, while the referee was knocked out — as referees often are — a second Doink emerged from beneath the ring to attack Crush before disappearing from whence he came. For that 45-second bit, Steve Keirn, who’d been wrestling as the alligator-hunting Skinner, hid under the ring, in full Doink regalia, for more than five hours.

Depending on whom you ask, the two Doinks were either a stroke of genius or a low mark at a point when business was struggling.

“For those of us that had to go through that time, I guess we kinda get slighted. ‘They didn’t do well. They didn’t draw well,’ ” says Michaels, who’s currently the Senior Vice President of Talent Development Creative at WWE. “A number of people did leave. And also from a character standpoint, like you mentioned the second Doink, I don’t know that creatively we were at our best at that time, either.”

The Undertaker’s worst match?

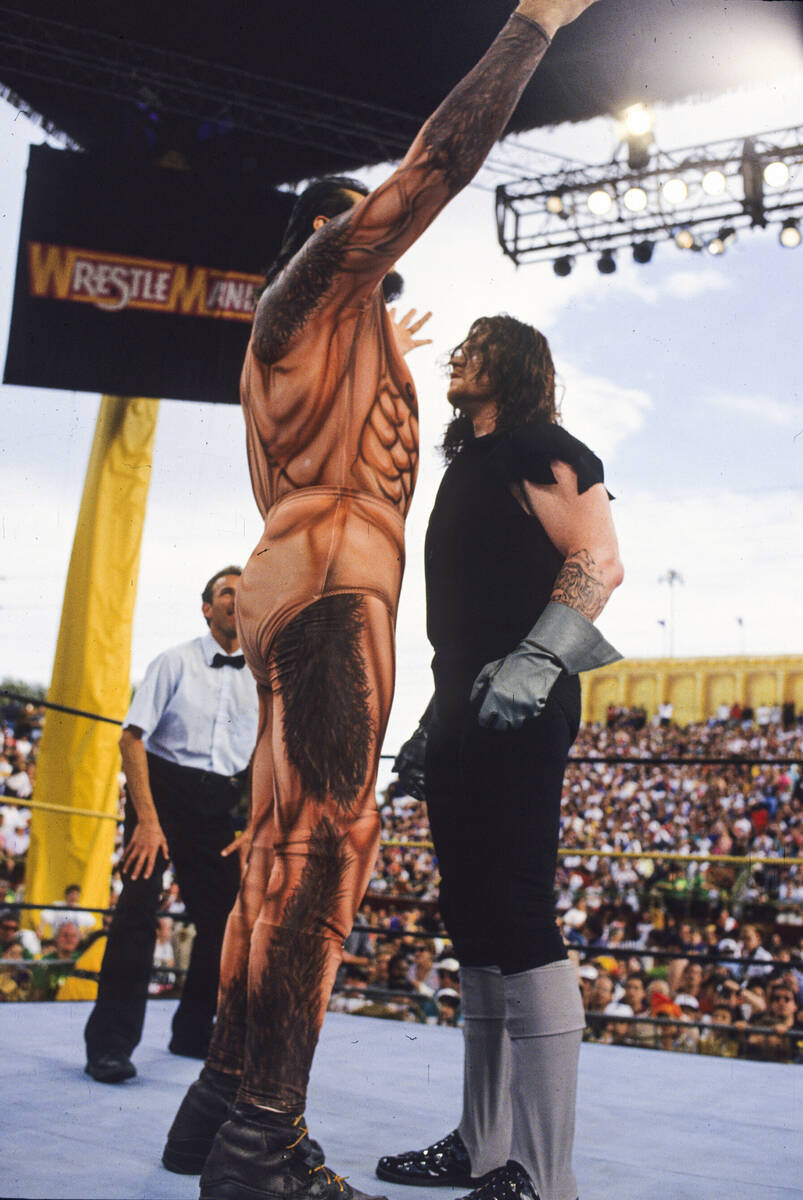

Those gimmicks, as ridiculous as they were, had nothing on Giant Gonzalez.

The character, if you can even call it that, was the second attempt to make a wrestling star out of 7-foot-7, 400-pound Argentinian basketball player Jorge Gonzalaz.

“He was just really physically limited, as you can imagine somebody that size,” Mark Calaway recalls. “And he had no clue, really, about our industry and how it worked.”

Before becoming The Undertaker, Calaway was familiar with Gonzalez from their days in World Championship Wrestling. He says he left that company for two reasons. The most well-known is that booker Ole Anderson told him people would never pay to see him wrestle.

The other?

“They’d asked me to work a program with Jorge,” Calaway says. “I was like, ‘Uhh, no thank you. This is not the place for me. And that’s definitely not the angle for me.’ Little did I know that he would follow me shortly thereafter.”

Calaway laughs throughout this, a stark contrast to the 30 years he spent dedicated to maintaining his stoic, otherworldly persona. While at Caesars Palace, he ate his meals in his room, lest anyone realize he wasn’t really the reanimated corpse of an Old West mortician.

And to think, Calaway’s trepidation came long before Gonzalez was outfitted with a flesh-colored bodysuit that didn’t match his skin tone, onto which were airbrushed muscles, hair and, most distractingly, an intergluteal cleft. (Google that one, too.)

It was the sort of thing you might end up buying, and maybe even wearing, during spring break on Florida’s Gulf Coast — and have zero memories the next morning of having done so.

“His outfit was atrocious,” Prichard admits, although he swears it looked better on paper. Gonzalez wasn’t comfortable with his body, he adds, so it was a way to cover him up and make him as comfortable as possible.

The truth is, there was no making Gonzalez look comfortable in the ring. He reacted to Calaway’s punches as though he were being attacked by a swarm of slow-moving bees. Calaway tried his best to carry the match, but he’d might as well have been wrestling a sofa.

“ ‘Just take your arm and hit me,’ ” Calaway says he told Gonzalez before the match. “ ‘I don’t care how hard you hit me, just hit me across the shoulder blades and let me do the work.’ And he couldn’t grasp that, right? He kept hitting me across the back of the neck. … He beat the crap out of me.”

Calaway stresses he doesn’t want to speak ill of Gonzalez, who died in 2010. The man was just trying to make a living after his basketball career didn’t pan out, despite being drafted by the Atlanta Hawks with the 54th pick in 1988. Calaway even utters “bless his heart” a couple of times for good measure.

Prichard, better known to older fans as red-faced preacher Brother Love, The Undertaker’s first manager, calls that match the worst of the legend’s acclaimed WWF/WWE career.

“Well, there’s a few that were stinkers, I have to admit,” Calaway says. “But that was probably the biggest ask of me, to try to make that something special.”

And that’s out of how many matches?

“I can’t even do the math. I mean thousands, thousands of matches.”

Still, that afternoon could’ve gone worse.

There could’ve been a second Giant Gonzalez hiding under the ring.

Hulkamania runs wild

WrestleMania IX’s reputation probably would’ve survived the double Doinks and even the stench of Giant Gonzalez if it hadn’t been for the Hulk Hogan of it all.

The Hulkster, who’d carried the company through its 1980s heyday, had been gone for a year after being implicated in the pending United States v. McMahon steroids trial.

He had his return match, teaming with his longtime friend Beefcake against IRS and “The Million Dollar Man” Ted DiBiase, and he was given more than enough time to pose in the ring. That should’ve been plenty.

But then outside interference cost champion Bret Hart his match against the pretend sumo wrestler Yokozuna and, for some nonsensical reason, Hogan ended up challenging the massive new champion for his title right then and there.

Hogan won the belt in 22 seconds.

“It was meant to be a holy (expletive) moment,” Prichard says. “For people to go, ‘Oh my God.’ To give them something extra.”

That was also, he says, the company’s first pay-per-view event that would have an encore showing during the week.

“Now we had something to promote. ‘Holy cow, now you get to see Hulk Hogan win the championship.’ People go, ‘What? Hulk wasn’t even in the match. How did this happen? I’ve gotta see this.’ ”

Still, Prichard admits, that ending “kinda left a bad taste in people’s mouths.”

It also sent something of a message to the locker room.

“That was a time we all felt like, ‘OK, we’re going into a new era,’ ” Michaels says, referring to the years of muscle-bound brutes hogging the spotlight until Hart became champion. “Us ‘smaller guys,’ as everybody says, and the guys that really worked on performance were going to get an opportunity to have the ball. And now it felt like we were taking a step back.”

‘Like an infomercial for Caesars Palace’

WrestleMania IX brought more than 15,000 fans to Caesars Palace and put the resort in front of viewers in more than 40 countries. It was even broadcast on the radio, as announcer Jim Ross noted during the show, “in most of these United States.”

At one point, the WWF’s over-caffeinated correspondent Todd Pettengill seemingly cut short an interview with singer Natalie Cole to get to Caesars Palace CEO Dan Reichartz.

“We’ve had word-class tennis. We’ve had ice hockey. We had the Olympic skaters. We had 80 world-class title bouts here, more than any other arena in the world,” Reichartz said. “This is the highest energy level we’ve ever had. Bar none.”

No one involved in bringing WrestleMania IX to the resort is still with the company, according to a representative for Caesars Entertainment. At the time, though, Caesars Palace officials told us the event was an easy way to attract its VIP clients and get them to bring their children.

In addition to the matches, the hotel hosted a charity version of “Family Feud,” pitting the good guys against the bad guys. The family-friendly Bagels, Biceps & Bacon Brunch served as something of a press conference hours before the event.

“Caesars, they were great to work with, man,” Prichard says. “They bent over backwards for us.”

Watching WrestleMania IX unfold, Iole recalls, “I’m going, ‘This is like an infomercial for Caesars Palace.’ ”

The spectacle survives

In the end, for something to which Caesars would forever be tied, it wasn’t the most beloved event.

But it may not have been as bad as its reputation.

“Well, I think that when you look at it from the matches and the card itself, it’s not as huge a box office as what WrestleMania was prior and what it became after. I don’t know that we necessarily delivered on all of that,” Prichard says. “I do think that it was better than people give it credit for.”

“Overall, when you go back and look at it,” he adds, “it was a huge spectacle.”

That spectacle, more than anything, is what’s stuck with Michaels all these years.

The man who’s seen pretty much everything in the world of pro wrestling still remembers his initial reaction to the exotic animals and the entrances that resembled a small-scale remake of “Ben-Hur.”

“You sit there,” Michaels says, “and go, ‘Wow, Vegas is just really different than any other place you’re ever gonna go.’ ”

Contact Christopher Lawrence at clawrence@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4567. Follow @life_onthecouch on Twitter.