Dad doesn’t want son following his example into drugs, gangs

Ten-year-old Montrel Lockhart rises from his uncle's couch -- his bed for now -- at the darkest hour just before dawn. The air bites. Even the nearby streets of downtown Las Vegas are deserted and lonely.

He's out the door in minutes to catch the 6 a.m. city bus, the first of three taking him to Craig Elementary School in North Las Vegas five miles away, but an hour's ride.

It's the same every school day, but when the bus pulls to the curb of Martin Luther King Boulevard near the U.S. Highway 95 overpass, Montrel smiles wide enough to reveal his silver caps. He gestures "ladies first" before boarding.

He's cheery despite the distress. Bright-eyed. Determined. He's going to be a pediatrician.

"I like babies," Montrel says, briefly pretending to cradle an infant in his arms while waiting for the second bus. His round cheeks glow with a hint of red from the cold.

The odds are stacked against Montrel, who isn't busing to a magnet school but an "at-risk" school in his family's old neighborhood, impoverished and crime-ridden.

But he's not alone.

His father, Demetrius, hobbles behind him from bus to bus every morning, makes sure he's safe, warm, wearing his jacket, which Montrel didn't want to wear this morning. But Demetrius won't have it.

So, Montrel grabs his jacket and tugs the zipper up to his chin within a few steps outside, pulling the hood over his head. "I thought you weren't cold," says Demetrius, smiling.

He's also there on the bus every afternoon, riding four hours a day. He wants to make sure Montrel breaks the cycle of falling from determination into drugs, from graduation to gangs, as he did after high school.

Unlike fathers proud to have sons follow in their footsteps, Demetrius is making certain Montrel walks beside him, showing Montrel where life has led him. He prays his son uses this hindsight to take a higher road away from the pitfalls Demetrius fell into as a fatherless teen. Those caverns consumed him for 25 years, until he crawled out in 2009.

HISTORY WON'T BE REPEATED

The father is open with Montrel about his crack-smoking, car-stealing, prison-spotted past that ended only two years ago when he cleaned up. He doesn't give much more detail than that, feeling a 10-year-old shouldn't hear it.

"He saw his daddy go through it, knows where it leads," Demetrius says as the bus rolls past a vacant lot of lean-tos and shopping carts. "When we pass by here I tell him, 'Look at that field of homeless.' "

Demetrius, 45, remembers being like his son, bright-eyed, optimistic and a good student, cherishing his childhood at Craig Elementary. Demetrius' mother lives down the street, where he grew up.

"My mama raised us all by herself," Demetrius says. His mother was a cocktail waitress at Fremont Hotel and cared for six boys on her own.

It's their neighborhood, their school, the one constant Demetrius can give Montrel. The school, like many in impoverished areas, may not have a stellar academic record, but it's theirs. It was good to Demetrius and it's been good for Montrel, an A and B student.

"People get killed near school," says Montrel, who praises the school despite the danger in the neighborhood. "This is my last year (at Craig). I don't want to leave."

Montrel pretends to wipe tears away.

"He's going to college," says Demetrius as he lays a hand on his son's head.

Montrel rarely sits quietly next to his dad. He chats up commuters on the crowded bus, making friends.

Even though it isn't much, everything Demetrius has goes to Montrel. Demetrius was a supervisor at The Las Vegas Club until 2008, but he can't work anymore because of his health, collecting $318 in monthly disability.

"I'm limited in what I can do," says Demetrius, who must use a cane to prevent ripping the staples in his groin. The staples are new but the injury is years old, beginning with a botched vasectomy that became infected. Doctors are still trying to fix it, but he can't work or keep up in walking to the bus, taking medication three times a day. It's not only a constant pain -- evident in the wincing as he walks -- but a relentless reminder.

"I can't even play with him the way I want to. It's hard."

AT RISK BUT ON TRACK

But Demetrius doesn't dwell on himself, says Montrel's principal, Kelly O'Rourke. Seeing a father struggling with so much but worrying only for his son gives her hope.

"They give me a little faith in humanity, (they) are why I stay here," says O'Rourke, noting that a good number of parents are involved at Craig. "They look at Lois Craig as their school."

O'Rourke, 44, is also dead set on breaking the cycle plaguing students of the "at-risk" school. Craig Elementary is labeled at-risk, along with 154 other Clark County schools, because a majority of students live in poverty, which statistics show has put children at risk for poor performance, dropping out and falling into trouble. The faltering economy has increased that number from 90 schools in two years.

O'Rourke sometimes ventures alone into the worst parts of the neighborhood to find parents who can't be reached by phone, as she did when some boys inappropriately touched a third-grade girl. O'Rourke went to the apartment building alone and climbed the stairs, surrounded by expletives spray painted up the wall.

"This sweet little girl lives here," she remembers thinking. She wondered if it was smart to come. But she kept going.

"Maybe it was stupid. Yeah, it was stupid," O'Rourke says. "I've been back to that apartment building a couple times."

A lot of students cycle through that complex, she says.

Nine out of 10 Craig students live in poverty. But that doesn't mean these kids can't claw their way out, says the principal who's climbed a steep learning curve at inner-city schools. The climb began abruptly in 1999 on her first day of teaching as she stood excitedly in front of a class in Von Tobel Middle School, just a few blocks north of Craig. She noticed a girl standing in the back and offered her a seat upfront.

"Really? (Expletive) you," responded the girl.

"I was in shock," O'Rourke says. "That first month of school I didn't think I could stay in teaching."

She followed her gut instinct, telling the girl to stand throughout the entire class or find a seat, instead of sending her to the principal's office.

Later, another student told her that's the best thing she could've done. She has come to understand why. Sending these students to the principal's office doesn't scare them like it would most students. It builds resentment and more of the same behavior. They may be acting out because they live in abusive homes and don't know any other way.

Being fair and giving students a choice can change the tide, as it did with that girl in the back of the room. She became close with O'Rourke. That girl used a thread and needle to sew her name into her hand, and showed it to O'Rourke. Self-mutilation is a sign of abuse.

"They're really just kids," O'Rourke says. "They may seem like adults, but they're just kids."

O'Rourke knows. She was there as a kid -- still has a chipped front tooth from being jumped on the swings at school in Colorado Springs, Colo.

She doesn't mind. It reminds her what these kids go through, keeps her open-minded like she was with Montrel when she started at Craig three years ago.

One day, she heard a staff member yelling at Montrel, mad because he was always sitting in the office early before school. O'Rourke talked to him, heard his story and discovered only one bus could get him there on time but arrived early. And his father rode with him every day.

LIKE FATHER, NOT LIKE SON

Demetrius says his father left his mother. He'd give his son a few bucks when needed.

"But he was never around," Demetrius says. "I'm going to be there for my kids."

He wants to make a difference in the lives of his three children, which is why he has been fighting for custody ever since he separated from his girlfriend in 2003.

While raising Montrel and waiting for a low-cost rental from the Southern Nevada Regional Housing Authority, he has been fighting for his sixth-grade twins, Demetriona and Frederick.

Out of nowhere though, he says, his ex-girlfriend called a few weeks ago and said, "Come and get her (Demetriona)." Demetrius wasn't going to let her change her mind and immediately borrowed someone's car.

The same thing happened three years ago with Montrel.

Demetriona, a thin girl with a few freckles sprinkled under her eyes like her dad, is now in his custody.

She says she prefers living with her dad and Montrel, but she misses her twin brother, Frederick. He misses her too, says Demetrius, who heard from the mother that Frederick was crying because he missed Demetriona.

While waiting for the third bus, the trio make a quick run into 7-Eleven. Montrel picks a small bag of Flaming Hot Fritos and tells the cashier to have a great day. Demetriona pours a cup of French vanilla hot chocolate. Demetrius doesn't buy a thing for himself.

"My friends will see me today and ask me for something. Na-ah," Demetrius says. "It's all for my kids."

A double-decker bus pulls up, and the kids rush to the upper level for an eagle-eye view. Demetrius stays on the bottom, taking a break from playful bantering with Demetriona over whether she could drive the bus. The two kids sit together sharing Fritos and hot chocolate as they gossip and play a game where one person tells the other who they have to ask out.

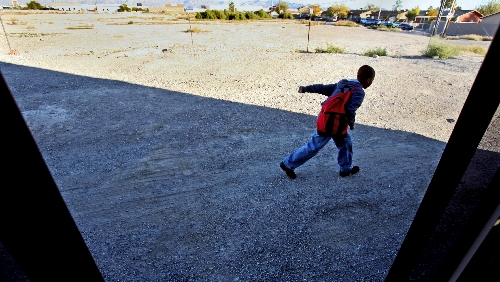

When the bus nears Craig Elementary, Montrel rushes down the steps.

Demetriona shouts, "I love you, Montrel."

"Love you," Montrel replies, as he bids his dad goodbye.

Montrel runs , his arms in the air like wings as he flies to school.

Demetrius rides the bus back, reaching his door as sleepy-eyed children walk to the school bus stop.

Contact reporter Trevon Milliard at tmilliard@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279.