Passing Nevada law to create MLK Day took years of perseverance

The Martin Luther King Jr. Day parade in Las Vegas is one of the longest-running of its kind in the nation. But it took years for Nevada to recognize the holiday it celebrates.

Six days after what would have been the civil rights leader’s 90th birthday, the Las Vegas Review-Journal revisited the fight to honor his legacy in Nevada and throughout the nation.

Nevada

A bill to make King’s birthday a state holiday was first introduced in the Legislature in 1983, a year after Las Vegas saw its first parade honoring him.

But even in a state where demonstrations as early as 1972 called for the holiday, the bill failed. At the time, 16 states and Washington, D.C., already recognized the holiday.

Another group of Nevada legislators, including then-Assemblyman Morse Arberry, tried again in 1985. Once again, though, the measure failed.

“I learned after that how to address the Legislature and not make it so sentimental and personal,” Arberry, who was a legislative freshman at the time, told the Review-Journal.

Those who opposed him in 1985 suggested that any new state holiday, regardless of whom it honored, would create a burden for the state’s coffers to have to pay holiday wages, according to legislative minutes from discussions at the time.

Arberry’s arguments, which came from the heart, powered the bill through the Assembly. But it died in the Senate.

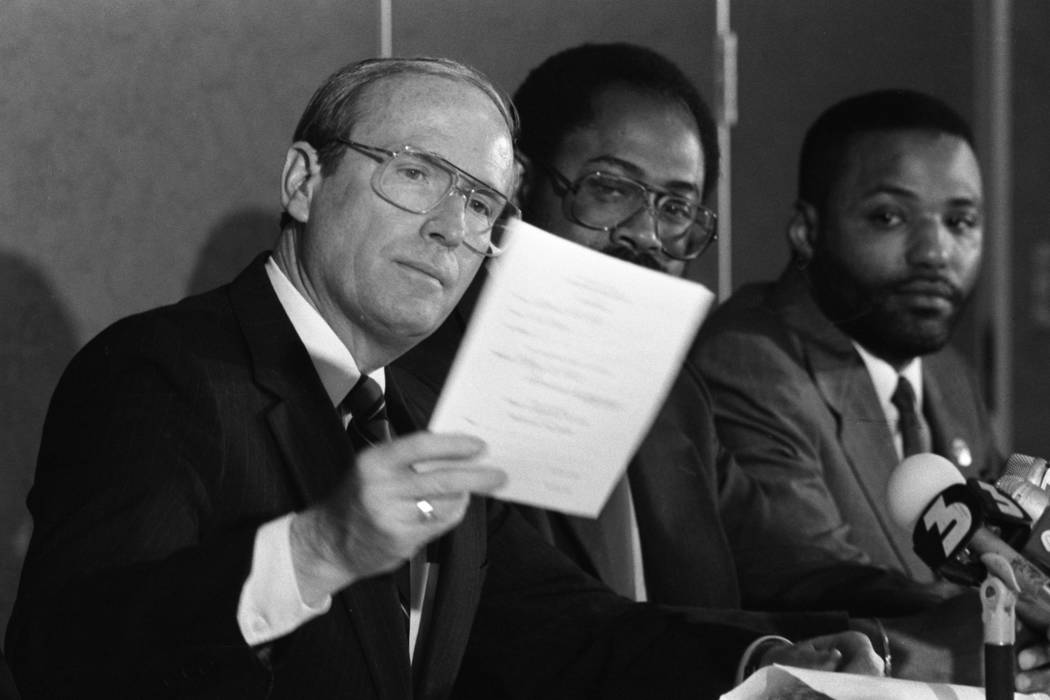

So in 1987, Arberry changed his approach. With the help of then-Assemblyman Wendell Williams and then-Sen. Joe Neal, Arberry argued that the holiday actually benefited Nevada economically.

“People are going to listen to dollars in Las Vegas a little more than (to) what’s right,” Williams told the Review-Journal last week.

In the 1987 session, the legislators centered their argument on California, which already recognized the King holiday.

They presented a documented spike in Las Vegas visitors from California over the three-day weekend. And because hotels on the Strip were already charging holiday rates for those rooms, the legislators presented a documented increase in state tax revenue.

“We were making money off a holiday we didn’t have,” Williams said.

With an eye on the economic fallout beginning to unfold in nearby Arizona, Nevada legislators ultimately passed the measure. Arizona didn’t recognize the holiday until a 1992 referendum and in 1990 lost the 1993 Super Bowl because of it.

For a few years before the Nevada Legislature approved the holiday, then-Gov. Richard Bryan was using one of two discretionary holidays allotted to him as governor to honor King anyway, a placeholder until it became state law.

Bryan signed the 1987 holiday measure into law in May. As part of it, the King holiday, as well as Family Day, the Friday after every Thanksgiving, replaced the discretionary holidays for state workers.

“I was very proud of the support we got,” Arberry said of the 1987 measure’s success. “I felt that they were showing that racism was fading with our generation. We were hoping that was taking place.”

Nation

In November 1983, the same year Nevada legislators first tried to recognize the King holiday, President Ronald Reagan signed it into federal law, allowing states the option to recognize it.

It was first observed in 1986.

But that, too, didn’t come without a fight.

Efforts to make King’s birthday a federal holiday first arose shortly after his 1968 assassination, spearheaded by his widow, Coretta Scott King.

Publicized pushback took two forms: cost, as Nevada legislators would later argue, and a break in tradition, because the honor of a holiday for someone who wasn’t a politician — let alone anyone — was not common, legislators at the time argued.

When King was killed, Columbus Day had been a national holiday for more than 30 years.

The House in 1983 ultimately passed the King holiday measure 333-90. A few months later, it passed in the Senate 78-22.

The vote brought Nevada’s Republican senators to a rare disagreement, Review-Journal archives show. Then-Sen. Paul Laxalt voted for the measure, calling it an “affirmation of black rights.”

Then-Sen. Chic Hecht voted against it, calling the cost factor “absolutely horrendous.”

“One other thing that is very important,” Hecht added, according to Review-Journal archives. “Suppose next year the Mexican-Americans come in for a holiday … or the Chinese-Americans … you know, we have started something that is going to be difficult to stop.”

Less than a month after the Senate vote, Reagan signed the bill into law at the heel of controversy.

Following the Senate vote that October, Reagan had publicly speculated whether files the FBI had collected on King through illegal wiretapping would one day show that the civil rights leader was a communist sympathizer.

The speculation prompted an apology to Coretta Scott King. Shortly after he scrawled his signature on the measure a few weeks later, he handed her the pen.

Now

All states now observe the King holiday, which falls on the third Monday of each January.

New Hampshire was the last state to conform. The state approved the day off in 1991 but called it Civil Rights Day until a 1999 measure, which officially named it after King.

Yet to this day, not all states reserve the holiday solely for King. Mississippi and Alabama share the holiday with Robert E. Lee. The Confederate general’s birthday falls on Jan. 19, four days after King’s.

“Racism is still kicking all over,” Arberry told the Review-Journal. “It’s worse sometimes today.”

Arberry said he looks to the annual King parade in Las Vegas as a sign of hope that pushed on even after the King holiday measure failed twice in Nevada. Over the past 37 years, it’s grown exponentially with Williams at the helm.

“I think it’s wonderful,” Arberry said. “Hopefully we can get past the little tit-for-tats in terms of racism and come together and make the community and the state a better place.”

Contact Rachel Crosby at rcrosby@reviewjournal or 702-477-3801. Follow @rachelacrosby.