‘Sky aglow with fire and death’: Pilot’s letter vividly recounts pilot’s D-Day mission

It wasn’t until 2014 that Las Vegas resident David Gibson’s brother found the letter their father penned 70 years earlier to his young wife about what he witnessed during the June 6, 1944, landings by Allied forces on the beach of Normandy, France.

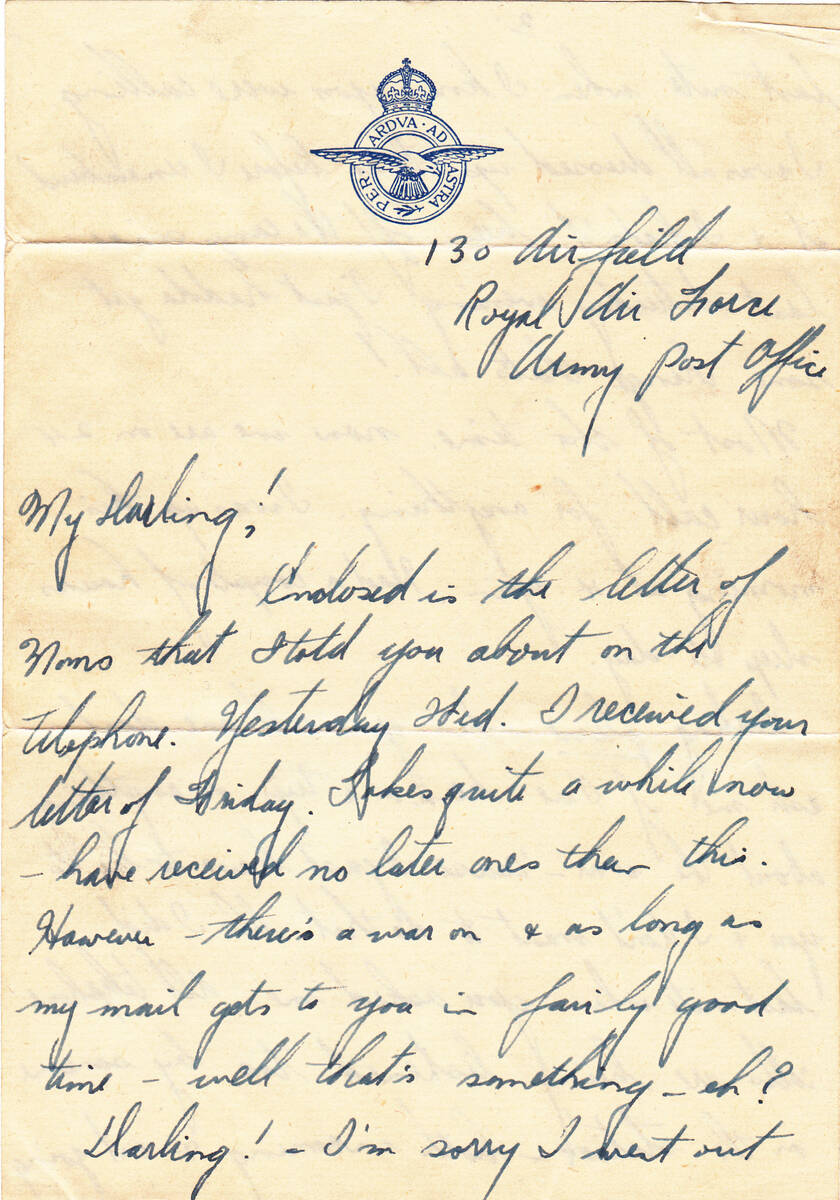

Gordon Gibson, a Royal Canadian Air Force reconnaissance pilot, wrote the remarkable letter to his 19-year-old British wife, Marjorie, just two days after the historic D-Day landings.

His job with others piloting P-51 Mustang single-seat planes was to fly parallel with the shore of Normandy, radio to an invading battleship after seeing tracer shells fired from the ship land and telling them where to adjust the aim to shoot explosive shells and destroy German army targets.

“We knew nothing about it until the evening before — when we were told the whole plan & our part in the actual landing operations,” the 24-year-old pilot penned on RAF stationery. “We were briefed that evening. I went to bed about 12 but I never slept a wink.”

After breakfast, Gordon Gibson and other Allied pilots were in the air by 5 a.m., flew in rain to a clear area and saw the open sea, he wrote.

“You’ve never seen ships until you’ve seen an invasion! I saw a thousand in 2 minutes! hundreds & hundreds! like little toys in a vast sea of grey — all heading one way. The sky was filled with aircraft — literally thousands.”

David Gibson, 66, a Las Vegas psychiatrist, said that his 77-year-old brother, Kendall Gibson, who lives in Canada, found the D-Day letter in an old wooden trunk filled with family mementos.

Kendall Gibson discovered the letter after the deaths of their father and mother among the many other letters their dad had written to her during World War II.

It was an amazing find for David and Kendall Gibson as well as their five brothers and one sister.

“When we first read that letter we were so surprised about how detailed it was,” David Gibson said, noting his father was raised on a dairy farm in Canada and had only a high school education. “I was talking to (Kendall) and he said my dad was a very good writer.”

That fateful day, June 6, 1944, Gordon Gibson was assigned, along with a pilot named Roy in another plane serving as his defensive wingman, to spot tracers fired by an American battleship and radio back to the ship to guide them to hit targets, according to David Gibson.

‘Like little fireflies flickering’

His dad wrote of being able to see flashes of gunfire 50 miles away as he flew over the English Channel toward France.

“Like little fireflies flickering in the twilight! In a matter of minutes, we were right in the thick if it. It was soul shaking,” he wrote. “The battle was just beginning. Hundreds of ships(s) were shelling the shore batteries with all they got! — and more! Their gun flashes lit up the sky over the sea! their shells rocked the coast like a tree in a hurricane. Pill boxes, shore guns, block houses went up in the air in dust like shovel fulls of sand.”

The description marked just the beginning of the letter capturing what he and his wingman experienced on D-Day.

“In 30 minutes all hell broke loose on the coast,” Gordon Gibson wrote. “Thousands of bombers poured down a devastating rain of bombs in patterns — carpeting whole towns — roads — bridges — german encampments! Villages & towns went up to 500 feet in dust — the bomb flashes rose to 1,000 feet — a vivid yellowish-red flame of death! Everything was on fire! Towns, woods! — the whole coast line in 20 minutes was covered in the smoke of battle to 4,000 feet! Petrol & ammo dumps blew sky high — sporting geysers of flame & billows of smoke like huge thunder clouds!”

‘Aglow with fire and death’

“The thousands of men came up in the landing barges their machine guns blazing low crimson arcs towards the shore! shells fell in the water all around — the german gunners on shore were trying desperately to stem the terrific overwhelming flood that was overtaking them! The sky was absolutely filled with flack. Five minutes after I was in it — I felt sure that before another 5 minutes went by I’d be dead. I was sure of it!”

“For the first few minutes after I was absolutely overcome. I was stiff in the cockpit — I couldn’t speak a word over the radio! To me there was only one place where there wasn’t any flack & that’s where my aircraft was. But somehow when we’d finished our task for that trip we were still intact. I don’t know how on earth Roy ever stayed with me! I could hardly see my targets at times! The whole area was covered in a pall of yellow-black smoke. The sky was aglow with fire and death.”

Close calls

Gordon Gibson and his wingman then had to return to England to refuel and “45 minutes later we were off again and again we were in that awful hail of lead. But if it was bad for us — it must have been terrific for the Jerries & for the boys down there in the barges.”

He wrote that in the next 30 minutes — at 6,000 feet in the air — his engine stopped. He radioed Roy to take over and “that I was going to have to crash-land in France. I picked a field & prepared myself for the bang! Why the Jerries never shot me to smithereens I dunno — I was a sitting target! By a stroke of luck or by the hand of God or something: on my last approach to the field at 500 feet I got the engine running — roughly — but running! Somehow! I can’t remember — I got back to England! Never have I seen such a wonderful sight as the coast looked then! I got back to home base about noon & wrote a short note to you and went to bed. I was dead — tired — my eyes ached like fire — I was played right out.”

“I have seen a bit of fightin’ — but never have I seen such a sight as Tuesday morning! — such an achievement — such a success! — against such odds! It was absolutely magnificent.”

“It was a wonderful show — I wouldn’t have missed it for anything. I am proud I was able to do my little wee bit to help it start on its way. If you wanta know the future honey — just put me to sleep & I’ll tell yuh — huh?!”

Switch in time

David Gibson said that his father did not mention it in the letter, but what happened when his plane started going down was that Gordon was running out of fuel and he had forgotten that he had another fuel tank but was able to switch over to it in time to keep flying.

After the war, Gordon Gibson stayed in the Royal Canadian Air Force on the home side as a flight trainer “but he never talked about the war too much,” David Gibson said.

One of his father’s jobs while flying during the war was to capture black-and-white films of certain targets from a camera mounted on his plane. One such target he filmed and reported by radio was a German train, which was later destroyed in a bombardment, David Gibson said.

Gordon Gibson returned in his plane to film the blown-up train, a film he kept and took home after the war, but he did not like his kids watching it, David Gibson said.

“I don’t know if he didn’t want us to watch it because he didn’t want it to get broken or he didn’t like us watching it and sort of glorifying this bombing of a train,” he said.

Contact Jeff Burbank at jburbank@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0382. Follow him @JeffBurbank2 on X.