After scrapping Sisolak’s climate plan, Lombardo releases his own

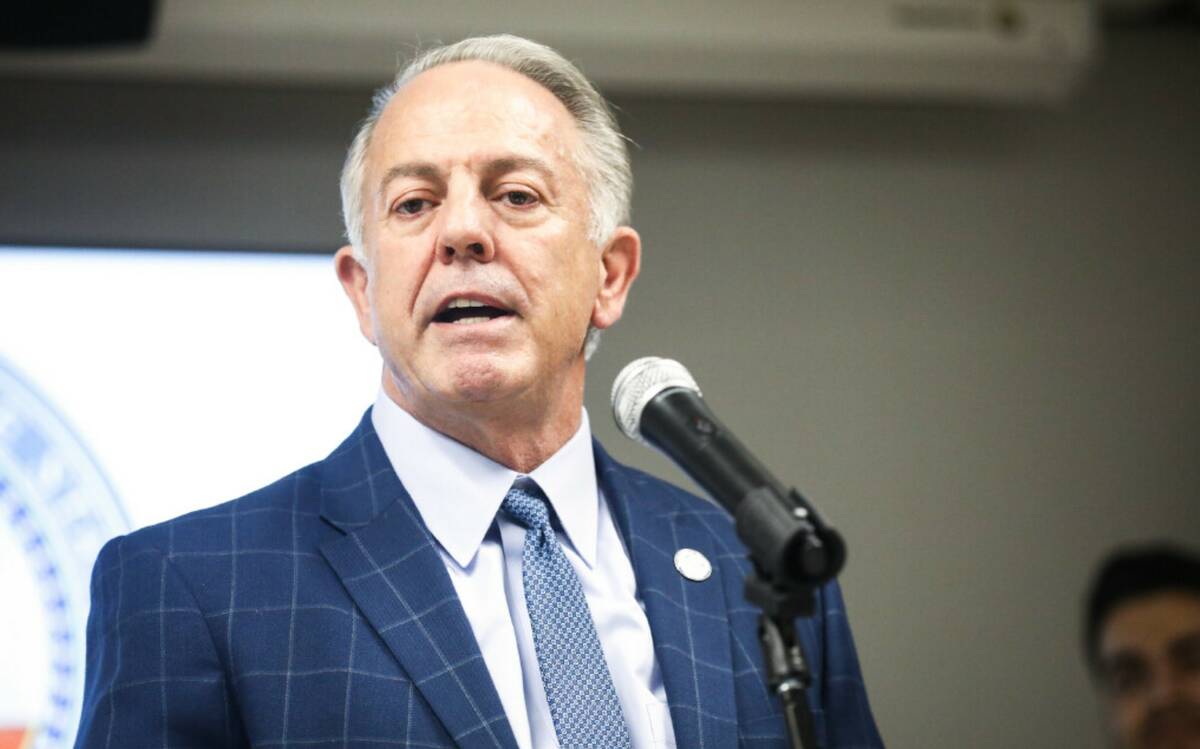

Almost two years after Gov. Joe Lombardo scrapped his Democratic predecessor’s statewide plan to address climate change, he released a shorter version this week that emphasizes Nevada’s mining industry and promotes clean energy.

The 33-page “Climate Innovation Plan” focuses on Nevada’s production of minerals needed to transition away from fossil fuels and the removal of federal red tape for clean energy projects. It’s much different from former Gov. Steve Sisolak’s 255-page plan, no longer available on the internet, that set clearer carbon emission reduction goals.

In a statement released online, Lombardo said the document addresses Nevada’s changing climate in a way that considers the economy and national security.

“By harnessing clean energy, improving energy efficiency, and fostering economic growth, we’re establishing Nevada as a leader in climate solutions,” Lombardo said. “By addressing these environmental challenges locally, we’re able to strengthen the future of our state for generations to come.”

The plan has drawn the ire of Nevada Democrats and some environmentalists who say it lacks a clear vision for combating climate change in what climate scientists say is the nation’s driest state with the two fastest-warming cities.

Lombardo also pulled Nevada from the multistate U.S. Climate Alliance in July 2023. Nevada’s state climatologist, Tom Albright, said he wasn’t consulted in the planning process.

The governor’s spokeswoman declined to make him available for an interview but said in a statement that the plan focused on “reducing carbon emissions without providing an unrealistic timeline for reduction.” Environmental stewardship isn’t a partisan issue, she added.

Gemma Smith, an Arizona State University public policy professor, said Nevada having a climate change mitigation plan at all is a positive. While cities and counties can put forth goals at the local level — like the All-In Clark County Plan — some issues require a statewide lens, such as policy encouraging the use of electric vehicles, she said.

But including no distinct data is to the new plan’s detriment, Smith said, especially when compared with Sisolak’s more comprehensive plan.

“It’s quite difficult to evaluate the new Nevada climate plan from a scientific or a policy perspective because it doesn’t really outline specific metrics or goals,” Smith said. “Still, there needs to be some sort of unifying vision.”

Sisolak said he had not yet read the new plan in full.

“It’s a step back from what we did,” he told the Las Vegas Review-Journal on Thursday. “We wanted something that could be measured and quantified, but he decided to go in a different direction.”

Assembly Minority Leader Philip “P.K.” O’Neill, R-Carson City, said in a brief phone interview that Lombardo’s plan corrects Sisolak’s lofty plan — a clear overreach of government, in his view.

“This brings things back into reality,” he said. “It’s attainable and realistic.”

How do plans compare?

Aside from helping clean energy projects go live faster and advocating for Nevada to produce important minerals such as lithium, used in electric vehicle batteries, Lombardo’s plan discusses managing wildfire threats and the agriculture industry’s efforts to sequester carbon, where carbon dioxide is stored in soil.

After listing seven goals, Lombardo’s plan lists dozens of initiatives already in motion, including various grants and ongoing programs like PFAS monitoring in the state’s water, efforts to establish more electric vehicle charging stations, and Nevada’s role in continued Colorado River negotiations.

It mentions Nevada’s contract with NZero, a green tech company that a ProPublica investigation found secured millions in government contracts without delivering carbon emission data it had promised.

Sisolak’s plan more heavily relied on citing available science and community engagement, consulting more than 1,500 people across the state via listening sessions.

The document notably spoke of how Nevada would work to implement Senate Bill 254, which set carbon emission reduction goals: 28 percent by 2025, 45 percent by 2030 and net-zero — or near-zero — by 2050.

Criticism and praise

Some Democratic legislators like Assemblywoman Selena La Rue Hatch and Assembly Speaker Steve Yeager took to social media to express their disappointment in the plan, which they think takes credit for some of the work put in motion under the Sisolak administration.

“If one of my students submitted an essay like this ‘climate plan,’ I would give it back to be rewritten,” wrote La Rue Hatch, a public schoolteacher in Washoe County who serves on the Legislature’s Joint Interim Natural Resources Committee. “Even my students know that taking credit for the work of others and offering vague statements with zero evidence to support them is not good enough.”

Attempts to reach the three Republican members of the committee Thursday were unsuccessful.

Doing everything in Nevada’s power to shorten timelines for new mining and energy projects on public land is important to the state’s much hotter future, O’Neill said.

It’s the same environmentalists who take green energy companies to court that are calling for emissions to be reduced, he said.

“Then they’ll turn around and say, ‘Hey, we need green energy,’ ” O’Neill said. “You can’t have it both ways.”

The Nevada Clean Energy Fund did not respond to a request for comment about the governor’s push to fast-track mining and clean energy. A Nevada Mining Association spokeswoman said the group’s president, Amanda Hilton, was not available to comment Thursday.

Environmental groups such as the Center for Biological Diversity, the Sierra Club and the Nevada Conservation League weighed in on the plan, characterizing it as one without an accountability function.

“We’re gutted to see Gov. Lombardo publish his alleged ‘Climate Innovation Plan’ without consultation or collaboration from the everyday people he represents, community organizations and conservation leaders in Nevada,” said Christi Cabrera-Georgeson, the Nevada Conservation League’s deputy director.

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X.