Nevada wages war on coronavirus mutants

RENO — The public health investigation into Nevada’s first reported case of a vaccine-resistant coronavirus strain out of South Africa began with a call from a Reno hospital to the Washoe County Health District.

A doctor at the hospital contacted the district in February to ask whether it might be worth analyzing a test specimen from a COVID-19 patient who recently had traveled to that country.

“I said, ‘Absolutely,’ ” recalled Heather Kerwin, the district’s epidemiology program manager. “Get it over to Pandori’s lab.’”

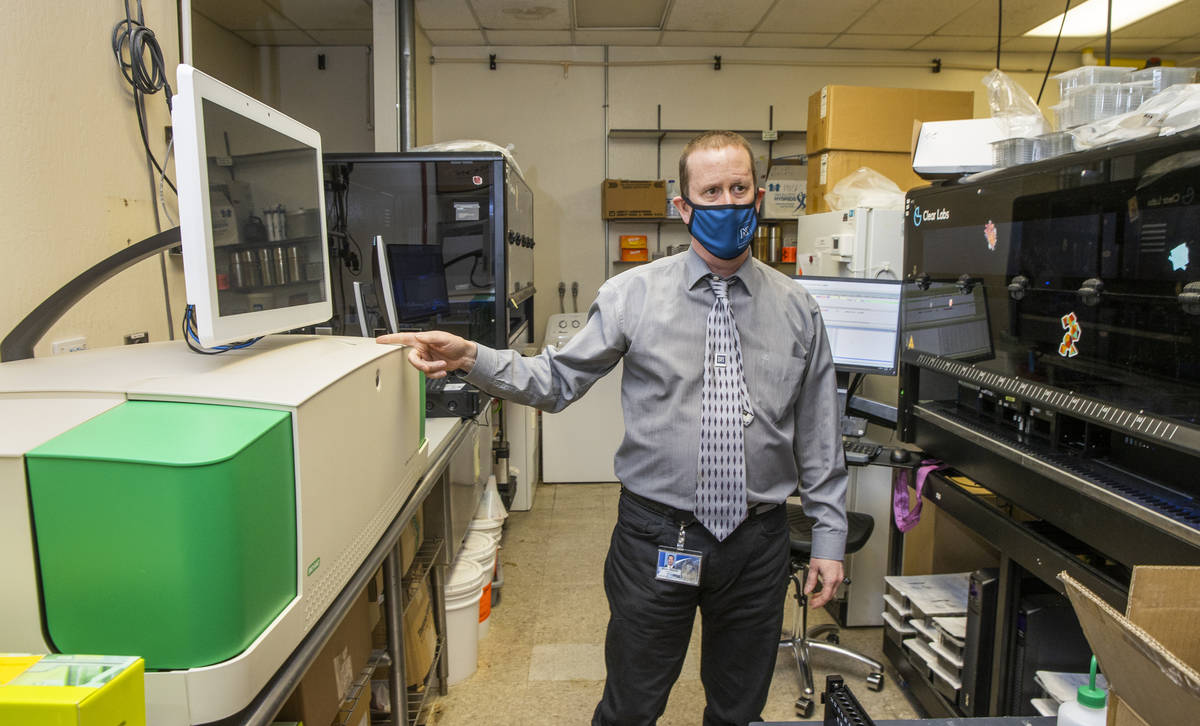

Mark Pandori is an associate professor with the University of Nevada, Reno, School of Medicine. He is also the director of the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory, located on campus in a low-slung beige building that looks a bit like a bunker. It is there that Nevada’s war on coronavirus mutants is staged each day, using advanced technology to combat the spread of potentially more deadly strains of the disease.

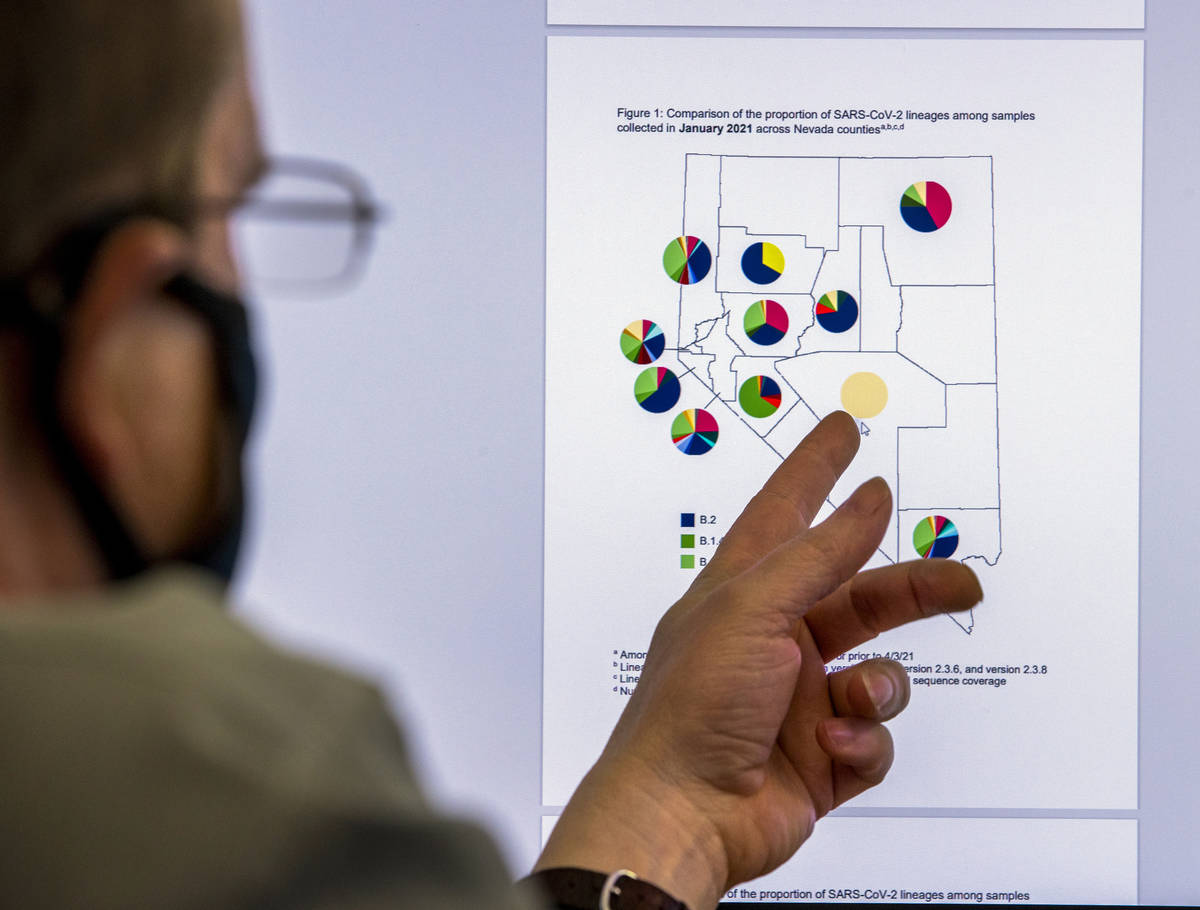

Pandori is leading the charge to analyze the genetic codes of the virus, using a sampling of positive test results from across the state. This analysis allows public health officials to track strains — also referred to as variants or, if you’re a scientist, lineages — that have evolved from the original virus first discovered in Wuhan, China.

Public health’s ‘dirty secret’

Like all viruses, the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 is constantly evolving through mutations, or errors, in genetic code that occur as it replicates. Many of the mutations make the virus no more or less dangerous. But researchers say that some mutations to the spike protein that gives the virus its crown-like shape have produced strains that are more infectious or are more likely to evade immunity developed through vaccination or prior infection. Some of these variants may also prove to be more lethal.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention refers to the more dangerous strains as “variants of concern.” They include strains first identified in South African, Brazil and the U.K. and a pair out of California. Cases of each have been reported in Nevada, where more than 100 strains have circulated since January 2020, though only roughly a dozen in significant numbers.

A “double mutant” variant out of India, a strain being closely monitored by the CDC because of two key mutations, also has been detected in Nevada.

Public health officials in the U.S. fear that these more troublesome variants could fuel a new surge in cases, hospitalizations and deaths.

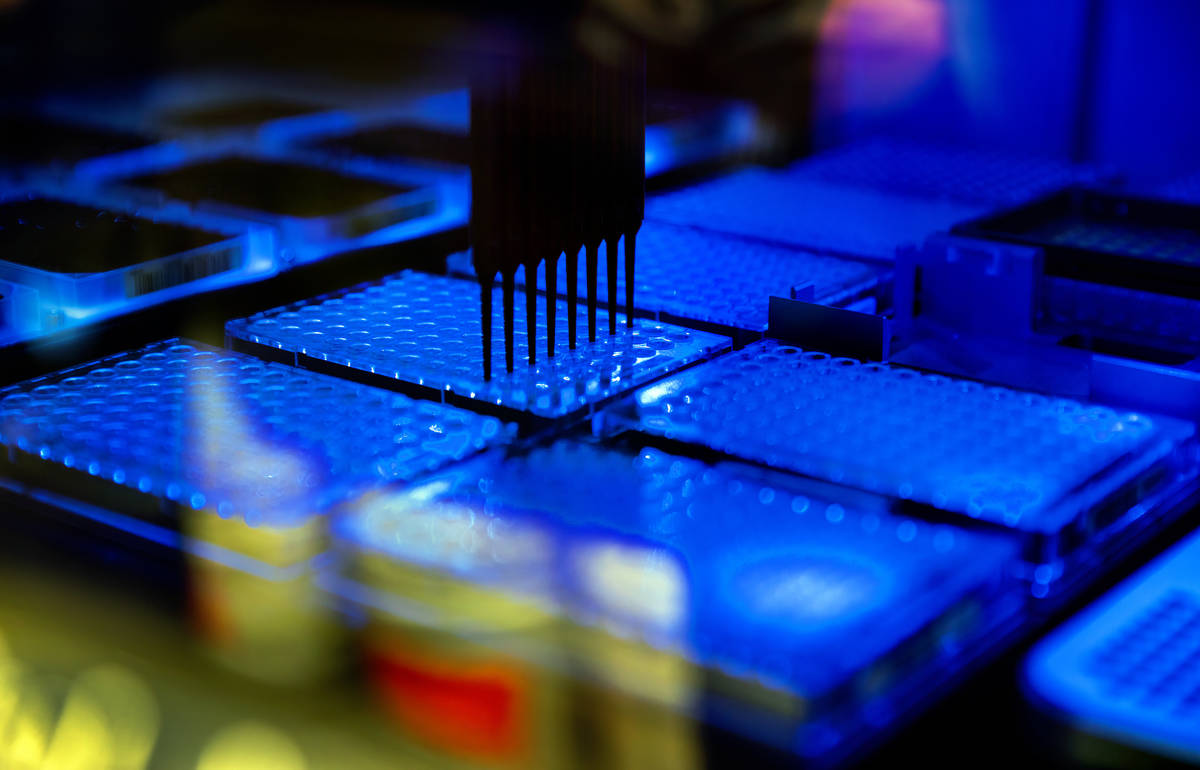

The team at the state lab in Reno uses test samples to conduct a form of genetic analysis referred to as sequencing, which examines the order of the RNA genome’s genetic code to determine its strain.

The lab shares the genetic analysis with the state’s county health districts.

“They can use that information to assist in disease control investigations or to understand better whether … cases within a cluster are related or unrelated,” Pandori said. “Or if it’s a particular variant of concern, does it require a particularly aggressive form of disease control and investigation.”

Last summer, sequencing was done at UNR’s Nevada Genomics Center, where director Paul Hartley developed an early method for analyzing COVID-19 specimens. The state lab has “transitioned to sequencing with an all-in-one automatic instrument that can provide sequencing data as quickly as one day, which is much faster than I can do it here,” Hartley said.

The current process begins with a machine that extracts RNA from a test specimen. Another machine completes a process called “thermal cycling” to detect whether the SARS-CoV2 virus is present. Lab staff take the extracted material and manually dilute the concentration of the RNA. From there, they load the material into an automated next-generation sequencer. The sequencer emails the data to staff, who upload it for analysis.

The lab uses cutting-edge equipment — one piece cost $900,000 — some of which was bought with funding from the CARES Act.

In mid-December, Pandori’s lab took things up a notch when it began to sequence all the COVID-19 tests it processes, as well as samples from across the state. The lab has been analyzing about 3 percent of the state’s positive tests. In March, the percentage rose to 6.5 percent, exceeding a goal of 5 percent recommended by many authorities. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also sequences a sampling of positive test results from Nevada processed by commercial labs.

The lab was “aggressive at building this technology in an automated fashion so that we could get genetic intelligence on a daily basis,” said Pandori, who studied genetics at University of California, Berkeley, obtained his doctorate in biomedical science/virology at UC San Diego and received fellowship training at Harvard Medical School. He joined the state lab in December 2019, just before the pandemic struck in Nevada in March of last year.

This intelligence can be used in real time to investigate case clusters and, potentially, to curb the spread of new, more dangerous variants. The key is to act quickly.

“The dirty secret is, public health is sort of powerless once an infectious disease has gotten down the road a little bit,” he said. “Really, our only power in public health is to intervene and prevent things.”

Variant invasion

Through sequencing, the public health lab confirmed that the Reno hospital’s case was the South African B.1.351 variant, which researchers believe is more contagious and better able to evade the protective antibodies produced by a person’s immune system.

The Washoe district began to call the known close contacts of the patient about their exposure to the virus and to advise them to self-quarantine so that if they were infected, they could avoid spreading the disease to anyone else. That is the county’s procedure for a positive case of any strain, Kerwin said.

The department began to search for unknown contacts. It reviewed video surveillance footage from a store the patient had visited to identify any employees or other customers with whom he had come into close contact.

“Their aggressive disease control has led to zero cases since then,” Pandori said.

The Washoe district prioritizes cases involving more dangerous variants. In cases of variants such as B.1.1.7 out of the U.K, which the CDC describes as 50 percent more infectious, it contacts individuals who test positive to tell them that they have a more contagious strain, if that information was not available at the time of the original exposure notification.

It also asks close contacts to self-quarantine for 14 days instead of the standard 10 days.

Not all investigations are as aggressive. The Southern Nevada Health District typically does not circle back to an individual with a case of a more dangerous variant or to that person’s close contacts, representatives said.

A disease surveillance supervisor for the health district in Clark County was uncertain if in March an individual with the state’s first reported case of the Brazilian P.1 variant or those with two subsequent cases were informed of the particular strain during case investigation or whether their contacts were given that information.

It would have depended on whether the detail had been available when notification was first made, said supervisor Kimberly Hertin, who did not recall the particulars of the cases. Typically the district would not make contact a second time, as its guidance for avoiding spreading the disease remains the same.

“The variants have a genetic difference that makes them either more transmissible or potentially less impacted by the vaccine, or (are) more common for reinfection,” Hertin said. “But the intervention in terms of preventing that person from exposing others is exactly the same.”

Hertin said that because the number of cases that are sequenced is limited, the odds are good that by the time a variant is discovered, it already will be spreading in the community.

“The discovery of the variant is often much later, after the circulation has begun,” she said.

The district’s Office of Epidemiology and Disease Surveillance “is updating its systems to reflect any variants of concern to monitor them to see if there are any commonalities or clusters based on data collected following an interview with the individual,” district representative Stephanie Bethel said.

Bethel said the three cases of the Brazilian variant did not appear to be linked. The health district did not make public these cases public until the Review-Journal first reported on them.

Researchers believe that the P.1 variant is fueling a surge in cases in South America, including in countries with high rates of vaccination.

Washoe case clusters

Even aggressive disease investigation and contact tracing may not be enough to stop a more infectious variant.

The Washoe health district interviewed 80 people in connection with its first case cluster involving the U.K. variant, Kerwin said. The district believes the original case was in a person from out of state visiting for a memorial service and related gatherings. Twenty cases of COVID-19 were traced to the events, three of which were confirmed as B.1.1.7. through sequencing, and more were suspected. Not all of the cases were sequenced because they involved people outside of Washoe’s jurisdiction.

The Washoe district also investigated a case cluster linked to a youth volleyball team, where team members, coaches and family members became ill after returning from an out-of-state tournament. Twenty-six confirmed cases of B.1.1.7 were tied to that cluster, Kerwin said.

“We know we’ve prevented the spread of cases” through investigations, Kerwin said

Despite such intensive efforts, the U.K. variant has become the dominant strain in Nevada, as it is in the U.S. as a whole.

Does it ever feel like the effort to stop the variants is futile?

“It certainly does feel like that, some days,” she acknowledged. “I think that public health is asking itself that.”

Vaccine intelligence

Kerwin, Hertin and Pandori all said that the information gleaned from tracking variants will be used to inform the development of new vaccines or vaccine boosters to combat the coronavirus.

“Six months from now, we’re going to be talking about the sequencing as it being a constant form of vaccine intelligence,” Pandori said.

The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines use genetic code to generate an immune response in the body. “And as it is a code, it can be changed easily, and we can start to use this sequence data to inform what codes should be in our next shot,” he said.

The amassing of intelligence is similar to the process for developing the flu vaccines each year, where researchers predict which strains they need to most protect against in the next influenza season.

Pandori, a war history buff, uses an arm race analogy to describe how COVID-19 vaccines must evolve to respond to an evolving virus.

“If you had a missile from the 1960s or the late ’50s that would have worked against the Soviet Union, do you think those same missiles would work now against a country like Russia?” he asked. “The answer is no because things have changed. The radars have changed … and the jamming technologies have changed.”

Likewise, for vaccines to evolve, researchers will need to learn continually about the enemy in their midst.

“It doesn’t mean that we’re not going to get hit again and again and again, very likely with different variants,” Pandori said. “But at least sequencing gives us an opportunity to understand when those variants are present. We can’t surrender.”

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com. Follow @MaryHynes1 on Twitter.