In the seven-day series The Water Question, the Review-Journal is taking an in-depth look at how long the river can sustain us, what’s being done to protect it and the implications for our community in the uncertain decades to come.

Water Question

Water was such an afterthought in rural Clark County in 1922 that the state’s representatives happily accepted the smallest share of the river in exchange for construction jobs, tax revenue and access to cheap electricity.

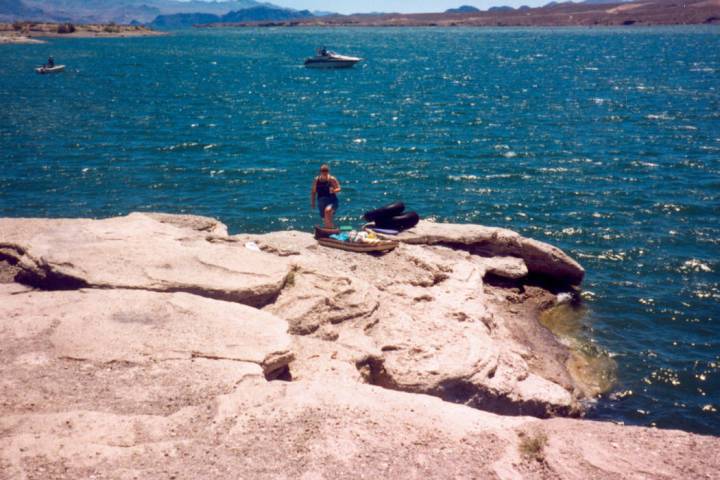

The Las Vegas Valley will still be able to access its share of the water through a deep new straw in Lake Mead, but its supplies are likely to be cut as river users in seven states deal with overuse of the resource.

Experts caution it won’t solve the underlying problems that are driving the overtaxed river’s decline and say more action will be needed to avoid a calamity.

The Las Vegas Valley already has reduced the amount of water it uses even as its population has grown substantially, but water managers say more savings will be required to meet the demands of growth.

Residents and cities are buying into the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s campaign against ornamental sod. Since 1999, more than 187 million square feet of grass have been removed and untold millions more were never planted.

Las Vegas Valley water managers opened the community’s first water savings account 20 years ago, literally banking on the day thevalley could no longer live on its Colorado River allotment alone.

Former Southern Nevada Water Authority chief Pat Mulroy is championing a plan that would leave more water in the Colorado and replace it with desalinated ocean water pumped from Mexico to Southern California.

It seems like a simple question: How many people can Southern Nevada support with the water it has now? But the answer is far from easy.

The community can continue to grow, so long as residents are willing to do what needs to be done to stretch that crucial — and finite — resource as far as it will go, experts say.