Pressure builds for Trump to change federal ethanol mandate — ANALYSIS

WASHINGTON — On the campaign trail, candidate Donald Trump embraced the federal mandate for ethanol in fuel — as many politicians, including Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush before him, did in the crush to grab votes in corn-rich Iowa.

As president, Trump has stuck by that campaign promise. But now free-market conservative groups and oil-state Republicans are pushing the administration to cut the corn cord.

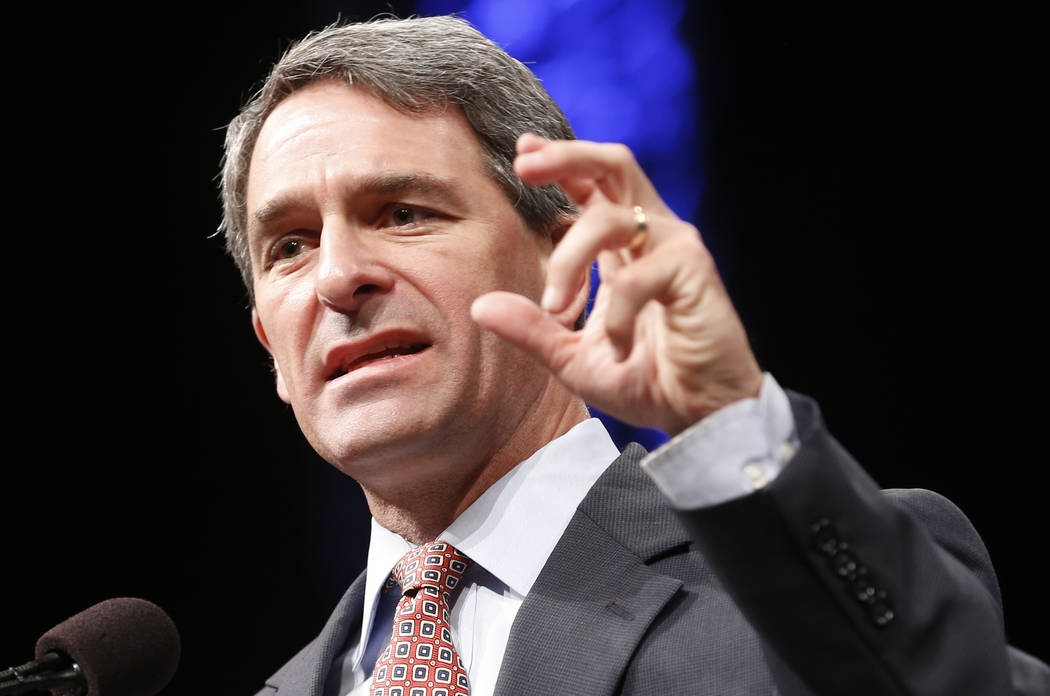

For Ken Cuccinelli of the conservative group FreedomWorks, it’s a moral issue. As the former GOP Virginia attorney general sees it, the ethanol mandate, which is part of Renewable Fuel Standards adopted in 2005 and 2007, drives up the price of both fuel and food.

“Any time you are driving up the price for the necessities of life” the poor pay a higher percentage of their incomes for basic needs, Cuccinelli said.

Like many government programs that reality has mugged, the fuel standards started with good intentions. The idea was to reduce America’s dependence on fossil fuels by requiring that renewable ethanol and other biofuels be added to the mix, which also was supposed to reduce greenhouse gases.

Thing is, the government mandates that refiners pay so much for biofuels that some 40 percent of U.S. corn is turned into ethanol, according to Scientific American, and much of the rest is exported.

And contrary to expectations, a 2014 Government Accountability Office report found that corn ethanol might lead to higher greenhouse gas emissions.

The test of time

Environmentalists now see a mandate that has led to over-farming and the environmental degradation that accompanies it.

Former Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., sent out a note last week in which he lamented that the RFS legislation he supported in 2007 “has not stood the test of time.” The letter accompanied a report by the Rethink Ethanol coalition that focused on the law’s devastating unintended consequences.

So who likes the program? Big Corn, politicians who represent corn country and presidential hopefuls who want to win in primaries and general elections in corn-rich Iowa.

Pro-ethanol pols aren’t afraid to remind candidates of their electoral clout. When U.S. ambassador to China Terry Branstad was governor of Iowa, he used to warn presidential hopefuls, “Don’t mess with the RFS.”

To keep the president on the ethanol train, Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, has read Trump’s pro-ethanol remarks on the Senate floor. In the fall, when Grassley heard Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency was considering reducing the required renewable fuels, Grassley railed, “I’ll make sure the EPA hears loud and clear the impact the EPA’s proposal will have on Iowa’s corn and soybean farmers and biofuel producers.”

The old-school approach to ethanol, however, might be crumbling.

Cuccinelli faulted the assumptions that drove the 2007 regulations. Officialdom predicted that Americans would be increasingly reliant on foreign fuel and that the U.S. fuel supply would continue to drop. Fracking upended those assumptions, which now are “devoid of any market reality.”

Politics of ethanol

The politics of ethanol are changing too. Trump supported ethanol in 2016, yet lost the Iowa caucus to Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, who braved conventional wisdom by opposing the scheme.

In December, Cruz and other oil-state lawmakers lobbied the White House for change, which could come from the EPA or Congress. Later Cruz told Fox News it was “a very positive and productive meeting.”

Liz Bowman, spokeswoman for EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, told the Review-Journal that Pruitt will continue to have discussions about forms “with regard to what we can realistically achieve, while following the statute.”

Scott Faber of the Environmental Working Group believes Pruitt has enormous discretion. After a decade fighting a good fix, Faber confessed, “It’s just really hard to see how you put together 60 votes in the Senate” to produce a reform package that makes sense.

“I think this is one of the biggest question marks going into 2018 in the regulatory universe,” Cuccinelli opined. How viable will it be for Trump to hold onto a program that drives up food and gasoline prices because it’s supposed to be good for the environment, even though many environmental groups have turned against it?

Contact Debra J. Saunders at dsaunders@reviewjournal.com or 202-662-7391. Follow @DebraJSaunders on Twitter.